Performance Pay Paradox

Performance Pay Paradox

Written By:

Bunji - Date published:

8:57 am, October 25th, 2010 - 32 comments

Categories: wages -

Tags: performance related pay, The Age of Absurdity

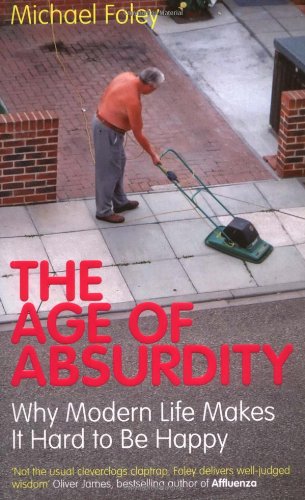

I’ve just finished a very good book: The Age of Absurdity by Michael Foley. It goes through various philosophical and other counter-measures to modern unhappiness. It’s very witty and thought-provoking – I can heartily recommend it.

I’ve just finished a very good book: The Age of Absurdity by Michael Foley. It goes through various philosophical and other counter-measures to modern unhappiness. It’s very witty and thought-provoking – I can heartily recommend it.

One of those thought-provoking ideas, whilst looking at the ‘absurdity of work’, is how increasing pay doesn’t increase motivation (decreasing it does permanently damage motivation and happiness with the job though). Greater autonomy and more challenging tasks are the only ways to increase satisfaction.

Coupled with that is the perverse way Performance Related Pay (PRP) de-motivates employees.

In theory PRP should cause better work as people want the money, so produce better results. In reality loss of goodwill means that work quality drops.

The psychologist Frederick Herzberg spent the second half of the twentieth century studying work motivation. He discovered 2 main flaws in PRP beyond the basic level “increasing money doesn’t increase motivation” effect.

The first is that it is often impossible to evaluate performance objectively and accurately.

The second is the assumption that if you change one aspect of work, everything else remains the same. In fact everything changes. Employees who fail to receive extra pay immediately stop doing anything beyond the base level of their job, so ‘voluntary’ work actually decreases, when it was precisely the opposite effect that was intended.

Introducing a financial incentive in fact decreases the satisfaction with the work. Psychologist Edward Deci had an experiment where 2 groups of people were given a series of puzzles to do, and upon completion of the task were allowed to continue with other similar puzzles if they wanted. He paid one group – they stopped soon after they finished the allotted tasks; he didn’t pay the other group – they continued doing the puzzles for over twice as long. Over 100 other studies have backed the same financial demotivation result.

In his book Foley relates the personal and uplifting experience of when performance pay was introduced – initially voluntarily – to his university. Managers were confident teachers would sign up for the extra cash, but were entirely disappointed as teachers knew the evaluations couldn’t be accurate and the rankings would be divisive. So management went personally to certain staff to convince them – and were turned down. Eventually, they just started paying certain teachers a performance bonus – only for those teachers to pool the cash and share it out equally amongst staff. Performance pay was rescinded, and never tried again.

(I’m now onto Nudge)

Related Posts

32 comments on “Performance Pay Paradox ”

- Comments are now closed

Links to post

-

The Standard: posted on 24 October 2010 at 1:04 am

-

Gabriella Turek: posted on 24 October 2010 at 1:36 am

-

iNeanderthal: posted on 24 October 2010 at 1:55 am

-

Matt Burgess: posted on 24 October 2010 at 8:17 am

-

The Standard: posted on 24 October 2010 at 7:53 pm

-

Gabriella Turek: posted on 24 October 2010 at 10:24 pm

- Comments are now closed

Recent Comments

- Ad on

- Tony Veitch on

- weka to Tiger Mountain on

- weka to UncookedSelachimorpha on

- newsense on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Mike the Lefty on

- Jilly Bee to Mike the Lefty on

- UncookedSelachimorpha to weka on

- Traveller to Drowsy M. Kram on

- newsense on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Traveller on

- observer on

- Ad on

- Phillip ure to Drowsy M. Kram on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Bearded Git on

- Phillip ure to Adrian on

- joe90 on

- Drowsy M. Kram to alwyn on

- Obtrectator to Mike the Lefty on

- Mike the Lefty to Obtrectator on

- Bearded Git to weka on

- Adrian to Phillip ure on

- Mike the Lefty to Obtrectator on

- Obtrectator on

- Bearded Git on

- Phillip ure on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Phillip ure on

- weka on

- Traveller on

- weka on

- Subliminal to tWig on

- Ad on

- tWig on

- Obtrectator to Anne on

- Obtrectator to ianmac on

- Phillip ure to Adrian on

- weka to Travellers on

- tWig on

- joe90 on

- Travellers to Adrian on

- Adrian on

- Adrian on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Anne on

- Phillip ure to Kay on

- ianmac on

- Phillip ure to aj on

- Grey Area to Descendant Of Smith on

- Gosman on

- Ad on

- newsense on

- Anne on

- joe90 on

- aj to Subliminal on

- aj to Phillip ure on

- adam to Phillip ure on

- tWig on

- Phillip ure to Traveller on

- Phillip ure to adam on

- Phillip ure to Kat on

- joe90 on

Recent Posts

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by Guest post

-

by advantage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by advantage

-

by weka

-

by nickkelly

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

- Some advice from our tertiary history for the University Advisory Group

Mike Grimshaw writes – The recent announcement of the University Advisory Group, chaired by Sir Peter Gluckman, makes very clear where the Government’s focus and priorities lie. The remit of the Advisory Group is that Group members will consider challenges and opportunities for improvement in the university sector including: ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 hours ago

Mike Grimshaw writes – The recent announcement of the University Advisory Group, chaired by Sir Peter Gluckman, makes very clear where the Government’s focus and priorities lie. The remit of the Advisory Group is that Group members will consider challenges and opportunities for improvement in the university sector including: ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 hours ago - Still no prudential regulation case around climate change

Eric Crampton writes – The Reserve Bank of New Zealand desperately wants to find reasons to have workstreams in climate change. It makes little sense. They’ve run another stress test on the banks looking to see if they could find a prudential regulation case. They couldn’t. They ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 hours ago

Eric Crampton writes – The Reserve Bank of New Zealand desperately wants to find reasons to have workstreams in climate change. It makes little sense. They’ve run another stress test on the banks looking to see if they could find a prudential regulation case. They couldn’t. They ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 hours ago - Bernard’s pick ‘n’ mix of the news links for Wednesday, April 24

TL;DR: These six news links stood out to me in the last 24 hours or so onWednesday, April 23:Scoop: 'Released in error': Treasury paper hints at axing $6b flood resilience plan by NZ Herald-$$$ Thomas CoughlanScoop: EY launches new misconduct review amid Fonterra ban. Fonterra tells EY to remove some ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 hours ago

TL;DR: These six news links stood out to me in the last 24 hours or so onWednesday, April 23:Scoop: 'Released in error': Treasury paper hints at axing $6b flood resilience plan by NZ Herald-$$$ Thomas CoughlanScoop: EY launches new misconduct review amid Fonterra ban. Fonterra tells EY to remove some ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 hours ago - How National can neutralise serious allegations of corruption should the “Fast Track” Bill becom...

Rob MacCullough writes – Pundits from the left and the right are arguing that National’s Fast Track Bill that is designed to speed up infrastructure decisions could end up becoming mired in a cesspool of corruption. Political commentator ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 hours ago

Rob MacCullough writes – Pundits from the left and the right are arguing that National’s Fast Track Bill that is designed to speed up infrastructure decisions could end up becoming mired in a cesspool of corruption. Political commentator ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 hours ago - Cleaning Up After Gabrielle.

Looking at the headlines this morning it’s hard to feel anything other than pessimistic about the future of humanity.Note that I’m not speaking about the future of mankind, but the survival of our humanity. The values that we believe in seem to be ebbing away, by the day.Perhaps every generation ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 hours ago

Looking at the headlines this morning it’s hard to feel anything other than pessimistic about the future of humanity.Note that I’m not speaking about the future of mankind, but the survival of our humanity. The values that we believe in seem to be ebbing away, by the day.Perhaps every generation ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 hours ago - Gordon Campbell on bird flu, AUKUS entry fees and Cindy Lee

Swabbing mixed breed baby chicks to test for avian influenzaUh oh. Bird flu – often deadly to humans – is not only being transmitted from infected birds to dairy cows, but is now travelling between dairy cows. As of last Friday, Bloomberg News reports, there were 32 American dairy herds ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon5 hours ago

Swabbing mixed breed baby chicks to test for avian influenzaUh oh. Bird flu – often deadly to humans – is not only being transmitted from infected birds to dairy cows, but is now travelling between dairy cows. As of last Friday, Bloomberg News reports, there were 32 American dairy herds ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon5 hours ago - Tolling Existing Roads

One of the government’s transport policy and agreements with it’s coalition partners made it clear that they were looking at options like tolling and road pricing. This was reinforced in it’s draft Government Policy Statement released at the start of March which made a couple of references to it. Road pricing, ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L7 hours ago

One of the government’s transport policy and agreements with it’s coalition partners made it clear that they were looking at options like tolling and road pricing. This was reinforced in it’s draft Government Policy Statement released at the start of March which made a couple of references to it. Road pricing, ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L7 hours ago - At a glance – The difference between weather and climate

On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a ...22 hours ago

On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a ...22 hours ago - More criminal miners

What is it with the mining industry? Its not enough for them to pillage the earth - they apparently can't even be bothered getting resource consent to do so: The proponent behind a major mine near the Clutha River had already been undertaking activity in the area without a ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant22 hours ago

What is it with the mining industry? Its not enough for them to pillage the earth - they apparently can't even be bothered getting resource consent to do so: The proponent behind a major mine near the Clutha River had already been undertaking activity in the area without a ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant22 hours ago - Photos from the road

Photo # 1 I am a huge fan of Singapore’s approach to housing, as described here two years ago by copying and pasting from The ConversationWhat Singapore has that Australia does not is a public housing developer, the Housing Development Board, which puts new dwellings on public and reclaimed land, ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack23 hours ago

Photo # 1 I am a huge fan of Singapore’s approach to housing, as described here two years ago by copying and pasting from The ConversationWhat Singapore has that Australia does not is a public housing developer, the Housing Development Board, which puts new dwellings on public and reclaimed land, ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack23 hours ago - RMA reforms aim to ease stock-grazing rules and reduce farmers’ costs – but Taxpayers’ Union w...

Buzz from the Beehive Reactions to news of the government’s readiness to make urgent changes to “the resource management system” through a Bill to amend the Resource Management Act (RMA) suggest a balanced approach is being taken. The Taxpayers’ Union says the proposed changes don’t go far enough. Greenpeace says ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin24 hours ago

Buzz from the Beehive Reactions to news of the government’s readiness to make urgent changes to “the resource management system” through a Bill to amend the Resource Management Act (RMA) suggest a balanced approach is being taken. The Taxpayers’ Union says the proposed changes don’t go far enough. Greenpeace says ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin24 hours ago - Luxon Strikes Out.

I’m starting to wonder if Anna Burns-Francis might be the best political interviewer we’ve got. That might sound unlikely to you, it came as a bit of a surprise to me.Jack Tame can be excellent, but has some pretty average days. I like Rebecca Wright on Newshub, she asks good ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 day ago

I’m starting to wonder if Anna Burns-Francis might be the best political interviewer we’ve got. That might sound unlikely to you, it came as a bit of a surprise to me.Jack Tame can be excellent, but has some pretty average days. I like Rebecca Wright on Newshub, she asks good ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 day ago - In many ways the media that the experts wanted, turned out to be the media they have got

Chris Trotter writes – Willie Jackson is said to be planning a “media summit” to discuss “the state of the media and how to protect Fourth Estate Journalism”. Not only does the Editor of The Daily Blog, Martyn Bradbury, think this is a good idea, but he has also ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54431 day ago

Chris Trotter writes – Willie Jackson is said to be planning a “media summit” to discuss “the state of the media and how to protect Fourth Estate Journalism”. Not only does the Editor of The Daily Blog, Martyn Bradbury, think this is a good idea, but he has also ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54431 day ago - The Waitangi Tribunal Summons; or the more things stay the same

Graeme Edgeler writes – This morning [April 21], the Wellington High Court is hearing a judicial review brought by Hon. Karen Chhour, the Minister for Children, against a decision of the Waitangi Tribunal. This is unusual, judicial reviews are much more likely to brought against ministers, rather than ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54431 day ago

Graeme Edgeler writes – This morning [April 21], the Wellington High Court is hearing a judicial review brought by Hon. Karen Chhour, the Minister for Children, against a decision of the Waitangi Tribunal. This is unusual, judicial reviews are much more likely to brought against ministers, rather than ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54431 day ago - Both Parliamentary watchdogs hammer Fast-track bill

Both of Parliament’s watchdogs have now ripped into the Government’s Fast-track Approvals Bill. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMy pick of the six newsey things to know from Aotearoa’s political economy and beyond on the morning of Tuesday, April 23 are:The Lead: The Auditor General, John Ryan, has joined the ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago

Both of Parliament’s watchdogs have now ripped into the Government’s Fast-track Approvals Bill. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMy pick of the six newsey things to know from Aotearoa’s political economy and beyond on the morning of Tuesday, April 23 are:The Lead: The Auditor General, John Ryan, has joined the ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago - India makes a big bet on electric buses

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Sarah Spengeman People wait to board an electric bus in Pune, India. (Image credit: courtesy of ITDP) Public transportation riders in Pune, India, love the city’s new electric buses so much they will actually skip an older diesel bus that ...1 day ago

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Sarah Spengeman People wait to board an electric bus in Pune, India. (Image credit: courtesy of ITDP) Public transportation riders in Pune, India, love the city’s new electric buses so much they will actually skip an older diesel bus that ...1 day ago - Bernard’s pick ‘n’ mix of the news links at 6:36am on Tuesday, April 23

TL;DR: These six news links stood out in the last 24 hours to 6:36am on Tuesday, April 22:Scoop & Deep Dive: How Sir Peter Jackson got to have his billion-dollar exit cake and eat Hollywood too NZ Herald-$$$ Matt NippertFast Track Approval Bill: Watchdogs seek substantial curbs on ministers' powers ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago

TL;DR: These six news links stood out in the last 24 hours to 6:36am on Tuesday, April 22:Scoop & Deep Dive: How Sir Peter Jackson got to have his billion-dollar exit cake and eat Hollywood too NZ Herald-$$$ Matt NippertFast Track Approval Bill: Watchdogs seek substantial curbs on ministers' powers ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago - What is really holding up infrastructure

The infrastructure industry yesterday issued a “hurry up” message to the Government, telling it to get cracking on developing a pipeline of infrastructure projects.The hiatus around the change of Government has seen some major projects cancelled and others delayed, and there is uncertainty about what will happen with the new ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 day ago

The infrastructure industry yesterday issued a “hurry up” message to the Government, telling it to get cracking on developing a pipeline of infrastructure projects.The hiatus around the change of Government has seen some major projects cancelled and others delayed, and there is uncertainty about what will happen with the new ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 day ago - “Pure Unadulterated Charge”

Hi,Over the weekend I revisited a podcast I really adore, Dead Eyes. It’s about a guy who got fired from Band of Brothers over two decades ago because Tom Hanks said he had “dead eyes”.If you don’t recall — 2001’s Band of Brothers was part of the emerging trend of ...David FarrierBy David Farrier1 day ago

Hi,Over the weekend I revisited a podcast I really adore, Dead Eyes. It’s about a guy who got fired from Band of Brothers over two decades ago because Tom Hanks said he had “dead eyes”.If you don’t recall — 2001’s Band of Brothers was part of the emerging trend of ...David FarrierBy David Farrier1 day ago - Bernard's six-stack of substacks for Monday, April 22

Tonight’s six-stack includes: writes via his substack that’s he’s sceptical about the IPSOS poll last week suggesting a slide into authoritarianism here, writing: Kiwis seem to want their cake and eat it too Tal Aster writes for about How Israel turned homeowners into YIMBYs. writes via his ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

Tonight’s six-stack includes: writes via his substack that’s he’s sceptical about the IPSOS poll last week suggesting a slide into authoritarianism here, writing: Kiwis seem to want their cake and eat it too Tal Aster writes for about How Israel turned homeowners into YIMBYs. writes via his ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - The media were given a little list and hastened to pick out Fast Track prospects – but the Treaty ...

Buzz from the Beehive The 180 or so recipients of letters from the Government telling them how to submit infrastructure projects for “fast track” consideration includes some whose project applications previously have been rejected by the courts. News media were quick to feature these in their reports after RMA Reform Minister Chris ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin2 days ago

Buzz from the Beehive The 180 or so recipients of letters from the Government telling them how to submit infrastructure projects for “fast track” consideration includes some whose project applications previously have been rejected by the courts. News media were quick to feature these in their reports after RMA Reform Minister Chris ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin2 days ago - Just trying to stay upright

It would not be a desirable way to start your holiday by breaking your back, your head, or your wrist, but on our first hour in Singapore I gave it a try.We were chatting, last week, before we started a meeting of Hazel’s Enviro Trust, about the things that can ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago

It would not be a desirable way to start your holiday by breaking your back, your head, or your wrist, but on our first hour in Singapore I gave it a try.We were chatting, last week, before we started a meeting of Hazel’s Enviro Trust, about the things that can ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago - “Unprecedented”

Today, former Port of Auckland CEO Tony Gibson went on trial on health and safety charges for the death of one of his workers. The Herald calls the trial "unprecedented". Firstly, it's only "unprecedented" because WorkSafe struck a corrupt and unlawful deal to drop charges against Peter Whittall over Pike ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago

Today, former Port of Auckland CEO Tony Gibson went on trial on health and safety charges for the death of one of his workers. The Herald calls the trial "unprecedented". Firstly, it's only "unprecedented" because WorkSafe struck a corrupt and unlawful deal to drop charges against Peter Whittall over Pike ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago - Bryce Edwards: Time for “Fast-Track Watch”

Calling all journalists, academics, planners, lawyers, political activists, environmentalists, and other members of the public who believe that the relationships between vested interests and politicians need to be scrutinised. We need to work together to make sure that the new Fast-Track Approvals Bill – currently being pushed through by the ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards2 days ago

Calling all journalists, academics, planners, lawyers, political activists, environmentalists, and other members of the public who believe that the relationships between vested interests and politicians need to be scrutinised. We need to work together to make sure that the new Fast-Track Approvals Bill – currently being pushed through by the ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards2 days ago - Gordon Campbell on fast track powers, media woes and the Tiktok ban

Feel worried. Shane Jones and a couple of his Cabinet colleagues are about to be granted the power to override any and all objections to projects like dams, mines, roads etc even if: said projects will harm biodiversity, increase global warming and cause other environmental harms, and even if ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon2 days ago

Feel worried. Shane Jones and a couple of his Cabinet colleagues are about to be granted the power to override any and all objections to projects like dams, mines, roads etc even if: said projects will harm biodiversity, increase global warming and cause other environmental harms, and even if ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon2 days ago - The Government’s new fast-track invitation to corruption

Bryce Edwards writes- The ability of the private sector to quickly establish major new projects making use of the urban and natural environment is to be supercharged by the new National-led Government. Yesterday it introduced to Parliament one of its most significant reforms, the Fast Track Approvals Bill. ...Point of OrderBy gadams10002 days ago

Bryce Edwards writes- The ability of the private sector to quickly establish major new projects making use of the urban and natural environment is to be supercharged by the new National-led Government. Yesterday it introduced to Parliament one of its most significant reforms, the Fast Track Approvals Bill. ...Point of OrderBy gadams10002 days ago - Maori push for parallel government structures

Michael Bassett writes – If you think there is a move afoot by the radical Maori fringe of New Zealand society to create a parallel system of government to the one that we elect at our triennial elections, you aren’t wrong. Over the last few days we have ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago

Michael Bassett writes – If you think there is a move afoot by the radical Maori fringe of New Zealand society to create a parallel system of government to the one that we elect at our triennial elections, you aren’t wrong. Over the last few days we have ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago - An announcement about an announcement

Without a corresponding drop in interest rates, it’s doubtful any changes to the CCCFA will unleash a massive rush of home buyers. Photo: Lynn GrievesonTL;DR: The six things that stood out to me in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, poverty and climate on Monday, April 22 included:The Government making a ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

Without a corresponding drop in interest rates, it’s doubtful any changes to the CCCFA will unleash a massive rush of home buyers. Photo: Lynn GrievesonTL;DR: The six things that stood out to me in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, poverty and climate on Monday, April 22 included:The Government making a ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - All the Green Tech in China.

Sunday was a lazy day. I started watching Jack Tame on Q&A, the interviews are usually good for something to write about. Saying the things that the politicians won’t, but are quite possibly thinking. Things that are true and need to be extracted from between the lines.As you might know ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago

Sunday was a lazy day. I started watching Jack Tame on Q&A, the interviews are usually good for something to write about. Saying the things that the politicians won’t, but are quite possibly thinking. Things that are true and need to be extracted from between the lines.As you might know ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago - Western Express Success

In our Weekly Roundup last week we covered news from Auckland Transport that the WX1 Western Express is going to get an upgrade next year with double decker electric buses. As part of the announcement, AT also said “Since we introduced the WX1 Western Express last November we have seen ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L2 days ago

In our Weekly Roundup last week we covered news from Auckland Transport that the WX1 Western Express is going to get an upgrade next year with double decker electric buses. As part of the announcement, AT also said “Since we introduced the WX1 Western Express last November we have seen ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L2 days ago - Bernard’s pick ‘n’ mix of the news links at 7:16am on Monday, April 22

TL;DR: These six news links stood out in the last 24 hours to 7:16am on Monday, April 22:Labour says Kiwis at greater risk from loan sharks as Govt plans to remove borrowing regulations NZ Herald Jenee TibshraenyHow did the cost of moving two schools blow out to more than $400m?A ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

TL;DR: These six news links stood out in the last 24 hours to 7:16am on Monday, April 22:Labour says Kiwis at greater risk from loan sharks as Govt plans to remove borrowing regulations NZ Herald Jenee TibshraenyHow did the cost of moving two schools blow out to more than $400m?A ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - The Kaka’s diary for the week to April 29 and beyond

TL;DR: The six key events to watch in Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy in the week to April 29 include:PM Christopher Luxon is scheduled to hold a post-Cabinet news conference at 4 pm today. Stats NZ releases its statutory report on Census 2023 tomorrow.Finance Minister Nicola Willis delivers a pre-Budget speech at ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

TL;DR: The six key events to watch in Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy in the week to April 29 include:PM Christopher Luxon is scheduled to hold a post-Cabinet news conference at 4 pm today. Stats NZ releases its statutory report on Census 2023 tomorrow.Finance Minister Nicola Willis delivers a pre-Budget speech at ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - 2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #16

A listing of 29 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, April 14, 2024 thru Sat, April 20, 2024. Story of the week Our story of the week hinges on these words from the abstract of a fresh academic ...3 days ago

A listing of 29 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, April 14, 2024 thru Sat, April 20, 2024. Story of the week Our story of the week hinges on these words from the abstract of a fresh academic ...3 days ago - Bryce Edwards: The Government’s new fast-track invitation to corruption

The ability of the private sector to quickly establish major new projects making use of the urban and natural environment is to be supercharged by the new National-led Government. Yesterday it introduced to Parliament one of its most significant reforms, the Fast Track Approvals Bill. The Government says this will ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards3 days ago

The ability of the private sector to quickly establish major new projects making use of the urban and natural environment is to be supercharged by the new National-led Government. Yesterday it introduced to Parliament one of its most significant reforms, the Fast Track Approvals Bill. The Government says this will ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards3 days ago - Thank you

This is a column to say thank you. So many of have been in touch since Mum died to say so many kind and thoughtful things. You’re wonderful, all of you. You’ve asked how we’re doing, how Dad’s doing. A little more realisation each day, of the irretrievable finality of ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago

This is a column to say thank you. So many of have been in touch since Mum died to say so many kind and thoughtful things. You’re wonderful, all of you. You’ve asked how we’re doing, how Dad’s doing. A little more realisation each day, of the irretrievable finality of ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago - Determining the Engine Type in Your Car

Identifying the engine type in your car is crucial for various reasons, including maintenance, repairs, and performance upgrades. Knowing the specific engine model allows you to access detailed technical information, locate compatible parts, and make informed decisions about modifications. This comprehensive guide will provide you with a step-by-step approach to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Identifying the engine type in your car is crucial for various reasons, including maintenance, repairs, and performance upgrades. Knowing the specific engine model allows you to access detailed technical information, locate compatible parts, and make informed decisions about modifications. This comprehensive guide will provide you with a step-by-step approach to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How to Become a Race Car Driver: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction: The allure of racing is undeniable. The thrill of speed, the roar of engines, and the exhilaration of competition all contribute to the allure of this adrenaline-driven sport. For those who yearn to experience the pinnacle of racing, becoming a race car driver is the ultimate dream. However, the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Introduction: The allure of racing is undeniable. The thrill of speed, the roar of engines, and the exhilaration of competition all contribute to the allure of this adrenaline-driven sport. For those who yearn to experience the pinnacle of racing, becoming a race car driver is the ultimate dream. However, the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How Many Cars Are There in the World in 2023? An Exploration of Global Automotive Statistics

Introduction Automobiles have become ubiquitous in modern society, serving as a primary mode of transportation and a symbol of economic growth and personal mobility. With countless vehicles traversing roads and highways worldwide, it begs the question: how many cars are there in the world? Determining the precise number is a ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Introduction Automobiles have become ubiquitous in modern society, serving as a primary mode of transportation and a symbol of economic growth and personal mobility. With countless vehicles traversing roads and highways worldwide, it begs the question: how many cars are there in the world? Determining the precise number is a ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How Long Does It Take for Car Inspection?

Maintaining a safe and reliable vehicle requires regular inspections. Whether it’s a routine maintenance checkup or a safety inspection, knowing how long the process will take can help you plan your day accordingly. This article delves into the factors that influence the duration of a car inspection and provides an ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Maintaining a safe and reliable vehicle requires regular inspections. Whether it’s a routine maintenance checkup or a safety inspection, knowing how long the process will take can help you plan your day accordingly. This article delves into the factors that influence the duration of a car inspection and provides an ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Who Makes Mazda Cars?

Mazda Motor Corporation, commonly known as Mazda, is a Japanese multinational automaker headquartered in Fuchu, Aki District, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. The company was founded in 1920 as the Toyo Cork Kogyo Co., Ltd., and began producing vehicles in 1931. Mazda is primarily known for its production of passenger cars, but ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Mazda Motor Corporation, commonly known as Mazda, is a Japanese multinational automaker headquartered in Fuchu, Aki District, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. The company was founded in 1920 as the Toyo Cork Kogyo Co., Ltd., and began producing vehicles in 1931. Mazda is primarily known for its production of passenger cars, but ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How Often to Replace Your Car Battery A Comprehensive Guide

Your car battery is an essential component that provides power to start your engine, operate your electrical systems, and store energy. Over time, batteries can weaken and lose their ability to hold a charge, which can lead to starting problems, power failures, and other issues. Replacing your battery before it ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Your car battery is an essential component that provides power to start your engine, operate your electrical systems, and store energy. Over time, batteries can weaken and lose their ability to hold a charge, which can lead to starting problems, power failures, and other issues. Replacing your battery before it ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Can You Register a Car Without a License?

In most states, you cannot register a car without a valid driver’s license. However, there are a few exceptions to this rule. Exceptions to the Rule If you are under 18 years old: In some states, you can register a car in your name even if you do not ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

In most states, you cannot register a car without a valid driver’s license. However, there are a few exceptions to this rule. Exceptions to the Rule If you are under 18 years old: In some states, you can register a car in your name even if you do not ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Mazda: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Reliability, Value, and Performance

Mazda, a Japanese automotive manufacturer with a rich history of innovation and engineering excellence, has emerged as a formidable player in the global car market. Known for its reputation of producing high-quality, fuel-efficient, and driver-oriented vehicles, Mazda has consistently garnered praise from industry experts and consumers alike. In this article, ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Mazda, a Japanese automotive manufacturer with a rich history of innovation and engineering excellence, has emerged as a formidable player in the global car market. Known for its reputation of producing high-quality, fuel-efficient, and driver-oriented vehicles, Mazda has consistently garnered praise from industry experts and consumers alike. In this article, ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - What Are Struts on a Car?

Struts are an essential part of a car’s suspension system. They are responsible for supporting the weight of the car and damping the oscillations of the springs. Struts are typically made of steel or aluminum and are filled with hydraulic fluid. How Do Struts Work? Struts work by transferring the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Struts are an essential part of a car’s suspension system. They are responsible for supporting the weight of the car and damping the oscillations of the springs. Struts are typically made of steel or aluminum and are filled with hydraulic fluid. How Do Struts Work? Struts work by transferring the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - What Does Car Registration Look Like: A Comprehensive Guide

Car registration is a mandatory process that all vehicle owners must complete annually. This process involves registering your car with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and paying an associated fee. The registration process ensures that your vehicle is properly licensed and insured, and helps law enforcement and other authorities ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Car registration is a mandatory process that all vehicle owners must complete annually. This process involves registering your car with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and paying an associated fee. The registration process ensures that your vehicle is properly licensed and insured, and helps law enforcement and other authorities ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How to Share Computer Audio on Zoom

Zoom is a video conferencing service that allows you to share your screen, webcam, and audio with other participants. In addition to sharing your own audio, you can also share the audio from your computer with other participants. This can be useful for playing music, sharing presentations with audio, or ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Zoom is a video conferencing service that allows you to share your screen, webcam, and audio with other participants. In addition to sharing your own audio, you can also share the audio from your computer with other participants. This can be useful for playing music, sharing presentations with audio, or ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How Long Does It Take to Build a Computer?

Building your own computer can be a rewarding and cost-effective way to get a high-performance machine tailored to your specific needs. However, it also requires careful planning and execution, and one of the most important factors to consider is the time it will take. The exact time it takes to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Building your own computer can be a rewarding and cost-effective way to get a high-performance machine tailored to your specific needs. However, it also requires careful planning and execution, and one of the most important factors to consider is the time it will take. The exact time it takes to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How to Put Your Computer to Sleep

Sleep mode is a power-saving state that allows your computer to quickly resume operation without having to boot up from scratch. This can be useful if you need to step away from your computer for a short period of time but don’t want to shut it down completely. There are ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Sleep mode is a power-saving state that allows your computer to quickly resume operation without having to boot up from scratch. This can be useful if you need to step away from your computer for a short period of time but don’t want to shut it down completely. There are ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - What is Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT)?

Introduction Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) has revolutionized the field of translation by harnessing the power of technology to assist human translators in their work. This innovative approach combines specialized software with human expertise to improve the efficiency, accuracy, and consistency of translations. In this comprehensive article, we will delve into the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Introduction Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) has revolutionized the field of translation by harnessing the power of technology to assist human translators in their work. This innovative approach combines specialized software with human expertise to improve the efficiency, accuracy, and consistency of translations. In this comprehensive article, we will delve into the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - iPad vs. Tablet Computers A Comprehensive Guide to Differences

In today’s digital age, mobile devices have become an indispensable part of our daily lives. Among the vast array of portable computing options available, iPads and tablet computers stand out as two prominent contenders. While both offer similar functionalities, there are subtle yet significant differences between these two devices. This ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

In today’s digital age, mobile devices have become an indispensable part of our daily lives. Among the vast array of portable computing options available, iPads and tablet computers stand out as two prominent contenders. While both offer similar functionalities, there are subtle yet significant differences between these two devices. This ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How Are Computers Made?

A computer is an electronic device that can be programmed to carry out a set of instructions. The basic components of a computer are the processor, memory, storage, input devices, and output devices. The Processor The processor, also known as the central processing unit (CPU), is the brain of the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

A computer is an electronic device that can be programmed to carry out a set of instructions. The basic components of a computer are the processor, memory, storage, input devices, and output devices. The Processor The processor, also known as the central processing unit (CPU), is the brain of the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How to Add Voice Memos from iPhone to Computer

Voice Memos is a convenient app on your iPhone that allows you to quickly record and store audio snippets. These recordings can be useful for a variety of purposes, such as taking notes, capturing ideas, or recording interviews. While you can listen to your voice memos on your iPhone, you ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Voice Memos is a convenient app on your iPhone that allows you to quickly record and store audio snippets. These recordings can be useful for a variety of purposes, such as taking notes, capturing ideas, or recording interviews. While you can listen to your voice memos on your iPhone, you ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Why My Laptop Screen Has Lines on It: A Comprehensive Guide

Laptop screens are essential for interacting with our devices and accessing information. However, when lines appear on the screen, it can be frustrating and disrupt productivity. Understanding the underlying causes of these lines is crucial for finding effective solutions. Types of Screen Lines Horizontal lines: Also known as scan ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Laptop screens are essential for interacting with our devices and accessing information. However, when lines appear on the screen, it can be frustrating and disrupt productivity. Understanding the underlying causes of these lines is crucial for finding effective solutions. Types of Screen Lines Horizontal lines: Also known as scan ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How to Right-Click on a Laptop

Right-clicking is a common and essential computer operation that allows users to access additional options and settings. While most desktop computers have dedicated right-click buttons on their mice, laptops often do not have these buttons due to space limitations. This article will provide a comprehensive guide on how to right-click ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Right-clicking is a common and essential computer operation that allows users to access additional options and settings. While most desktop computers have dedicated right-click buttons on their mice, laptops often do not have these buttons due to space limitations. This article will provide a comprehensive guide on how to right-click ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Where is the Power Button on an ASUS Laptop?

Powering up and shutting down your ASUS laptop is an essential task for any laptop user. Locating the power button can sometimes be a hassle, especially if you’re new to ASUS laptops. This article will provide a comprehensive guide on where to find the power button on different ASUS laptop ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Powering up and shutting down your ASUS laptop is an essential task for any laptop user. Locating the power button can sometimes be a hassle, especially if you’re new to ASUS laptops. This article will provide a comprehensive guide on where to find the power button on different ASUS laptop ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How to Start a Dell Laptop: A Comprehensive Guide

Dell laptops are renowned for their reliability, performance, and versatility. Whether you’re a student, a professional, or just someone who needs a reliable computing device, a Dell laptop can meet your needs. However, if you’re new to Dell laptops, you may be wondering how to get started. In this comprehensive ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Dell laptops are renowned for their reliability, performance, and versatility. Whether you’re a student, a professional, or just someone who needs a reliable computing device, a Dell laptop can meet your needs. However, if you’re new to Dell laptops, you may be wondering how to get started. In this comprehensive ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Bryce Edwards: Serious populist discontent is bubbling up in New Zealand

Two-thirds of the country think that “New Zealand’s economy is rigged to advantage the rich and powerful”. They also believe that “New Zealand needs a strong leader to take the country back from the rich and powerful”. These are just two of a handful of stunning new survey results released ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards4 days ago

Two-thirds of the country think that “New Zealand’s economy is rigged to advantage the rich and powerful”. They also believe that “New Zealand needs a strong leader to take the country back from the rich and powerful”. These are just two of a handful of stunning new survey results released ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards4 days ago - How to Take a Screenshot on an Asus Laptop A Comprehensive Guide with Detailed Instructions and Illu...

In today’s digital world, screenshots have become an indispensable tool for communication and documentation. Whether you need to capture an important email, preserve a website page, or share an error message, screenshots allow you to quickly and easily preserve digital information. If you’re an Asus laptop user, there are several ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

In today’s digital world, screenshots have become an indispensable tool for communication and documentation. Whether you need to capture an important email, preserve a website page, or share an error message, screenshots allow you to quickly and easily preserve digital information. If you’re an Asus laptop user, there are several ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How to Factory Reset Gateway Laptop A Comprehensive Guide

A factory reset restores your Gateway laptop to its original factory settings, erasing all data, apps, and personalizations. This can be necessary to resolve software issues, remove viruses, or prepare your laptop for sale or transfer. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to factory reset your Gateway laptop: Method 1: ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

A factory reset restores your Gateway laptop to its original factory settings, erasing all data, apps, and personalizations. This can be necessary to resolve software issues, remove viruses, or prepare your laptop for sale or transfer. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to factory reset your Gateway laptop: Method 1: ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - The Folly Of Impermanence.

“You talking about me?” The neoliberal denigration of the past was nowhere more unrelenting than in its depiction of the public service. The Post Office and the Railways were held up as being both irremediably inefficient and scandalously over-manned. Playwright Roger Hall’s “Glide Time” caricatures were presented as accurate depictions of ...4 days ago

“You talking about me?” The neoliberal denigration of the past was nowhere more unrelenting than in its depiction of the public service. The Post Office and the Railways were held up as being both irremediably inefficient and scandalously over-manned. Playwright Roger Hall’s “Glide Time” caricatures were presented as accurate depictions of ...4 days ago - A crisis of ambition

Roger Partridge writes – When the Coalition Government took office last October, it inherited a country on a precipice. With persistent inflation, decades of insipid productivity growth and crises in healthcare, education, housing and law and order, it is no exaggeration to suggest New Zealand’s first-world status was ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago

Roger Partridge writes – When the Coalition Government took office last October, it inherited a country on a precipice. With persistent inflation, decades of insipid productivity growth and crises in healthcare, education, housing and law and order, it is no exaggeration to suggest New Zealand’s first-world status was ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago - Have 308 people in the Education Ministry’s Curriculum Development Team spent over $100m on a 60-p...

Rob MacCulloch writes – In 2022, the Curriculum Centre at the Ministry of Education employed 308 staff, according to an Official Information Request. Earlier this week it was announced 202 of those staff were being cut. When you look up “The New Zealand Curriculum” on the Ministry of ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago

Rob MacCulloch writes – In 2022, the Curriculum Centre at the Ministry of Education employed 308 staff, according to an Official Information Request. Earlier this week it was announced 202 of those staff were being cut. When you look up “The New Zealand Curriculum” on the Ministry of ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago - 'This bill is dangerous for the environment and our democracy'

Chris Bishop’s bill has stirred up a hornets nest of opposition. Photo: Lynn Grieveson for The KākāTL;DR: The six things that stood out to me in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, poverty and climate from the last day included:A crescendo of opposition to the Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill is ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

Chris Bishop’s bill has stirred up a hornets nest of opposition. Photo: Lynn Grieveson for The KākāTL;DR: The six things that stood out to me in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, poverty and climate from the last day included:A crescendo of opposition to the Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill is ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - The Bank of our Tamariki and Mokopuna.

Monday left me brokenTuesday, I was through with hopingWednesday, my empty arms were openThursday, waiting for love, waiting for loveThe end of another week that left many of us asking WTF? What on earth has NZ gotten itself into and how on earth could people have voluntarily signed up for ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago

Monday left me brokenTuesday, I was through with hopingWednesday, my empty arms were openThursday, waiting for love, waiting for loveThe end of another week that left many of us asking WTF? What on earth has NZ gotten itself into and how on earth could people have voluntarily signed up for ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago - The worth of it all

Hello! Here comes the Saturday edition of More Than A Feilding, catching you up on the past week’s editions.State of humanity, 20242024, it feels, keeps presenting us with ever more challenges, ever more dismay.Do you give up yet? It seems to ask.No? How about this? Or this?How about this?Full story Share ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack4 days ago

Hello! Here comes the Saturday edition of More Than A Feilding, catching you up on the past week’s editions.State of humanity, 20242024, it feels, keeps presenting us with ever more challenges, ever more dismay.Do you give up yet? It seems to ask.No? How about this? Or this?How about this?Full story Share ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack4 days ago - What is the Hardest Sport in the World?

Determining the hardest sport in the world is a subjective matter, as the difficulty level can vary depending on individual abilities, physical attributes, and experience. However, based on various factors including physical demands, technical skills, mental fortitude, and overall accomplishment, here is an exploration of some of the most challenging ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Determining the hardest sport in the world is a subjective matter, as the difficulty level can vary depending on individual abilities, physical attributes, and experience. However, based on various factors including physical demands, technical skills, mental fortitude, and overall accomplishment, here is an exploration of some of the most challenging ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - What is the Most Expensive Sport?

The allure of sport transcends age, culture, and geographical boundaries. It captivates hearts, ignites passions, and provides unparalleled entertainment. Behind the spectacle, however, lies a fascinating world of financial investment and expenditure. Among the vast array of competitive pursuits, one question looms large: which sport carries the hefty title of ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

The allure of sport transcends age, culture, and geographical boundaries. It captivates hearts, ignites passions, and provides unparalleled entertainment. Behind the spectacle, however, lies a fascinating world of financial investment and expenditure. Among the vast array of competitive pursuits, one question looms large: which sport carries the hefty title of ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Pickleball On the Cusp of Olympic Glory

Introduction Pickleball, a rapidly growing paddle sport, has captured the hearts and imaginations of millions around the world. Its blend of tennis, badminton, and table tennis elements has made it a favorite among players of all ages and skill levels. As the sport’s popularity continues to surge, the question on ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Introduction Pickleball, a rapidly growing paddle sport, has captured the hearts and imaginations of millions around the world. Its blend of tennis, badminton, and table tennis elements has made it a favorite among players of all ages and skill levels. As the sport’s popularity continues to surge, the question on ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - The Origin and Evolution of Soccer Unveiling the Genius Behind the World’s Most Popular Sport

Abstract: Soccer, the global phenomenon captivating millions worldwide, has a rich history that spans centuries. Its origins trace back to ancient civilizations, but the modern version we know and love emerged through a complex interplay of cultural influences and innovations. This article delves into the fascinating journey of soccer’s evolution, ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Abstract: Soccer, the global phenomenon captivating millions worldwide, has a rich history that spans centuries. Its origins trace back to ancient civilizations, but the modern version we know and love emerged through a complex interplay of cultural influences and innovations. This article delves into the fascinating journey of soccer’s evolution, ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How Much to Tint Car Windows A Comprehensive Guide

Tinting car windows offers numerous benefits, including enhanced privacy, reduced glare, UV protection, and a more stylish look for your vehicle. However, the cost of window tinting can vary significantly depending on several factors. This article provides a comprehensive guide to help you understand how much you can expect to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Tinting car windows offers numerous benefits, including enhanced privacy, reduced glare, UV protection, and a more stylish look for your vehicle. However, the cost of window tinting can vary significantly depending on several factors. This article provides a comprehensive guide to help you understand how much you can expect to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Why Does My Car Smell Like Gas? A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosing and Fixing the Issue

The pungent smell of gasoline in your car can be an alarming and potentially dangerous problem. Not only is the odor unpleasant, but it can also indicate a serious issue with your vehicle’s fuel system. In this article, we will explore the various reasons why your car may smell like ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

The pungent smell of gasoline in your car can be an alarming and potentially dangerous problem. Not only is the odor unpleasant, but it can also indicate a serious issue with your vehicle’s fuel system. In this article, we will explore the various reasons why your car may smell like ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How to Remove Tree Sap from Car A Comprehensive Guide

Tree sap can be a sticky, unsightly mess on your car’s exterior. It can be difficult to remove, but with the right techniques and products, you can restore your car to its former glory. Understanding Tree Sap Tree sap is a thick, viscous liquid produced by trees to seal wounds ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Tree sap can be a sticky, unsightly mess on your car’s exterior. It can be difficult to remove, but with the right techniques and products, you can restore your car to its former glory. Understanding Tree Sap Tree sap is a thick, viscous liquid produced by trees to seal wounds ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - How Much Paint Do You Need to Paint a Car?

The amount of paint needed to paint a car depends on a number of factors, including the size of the car, the number of coats you plan to apply, and the type of paint you are using. In general, you will need between 1 and 2 gallons of paint for ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

The amount of paint needed to paint a car depends on a number of factors, including the size of the car, the number of coats you plan to apply, and the type of paint you are using. In general, you will need between 1 and 2 gallons of paint for ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Can You Jump a Car in the Rain? Safety Precautions and Essential Steps

Jump-starting a car is a common task that can be performed even in adverse weather conditions like rain. However, safety precautions and proper techniques are crucial to avoid potential hazards. This comprehensive guide will provide detailed instructions on how to safely jump a car in the rain, ensuring both your ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago

Jump-starting a car is a common task that can be performed even in adverse weather conditions like rain. However, safety precautions and proper techniques are crucial to avoid potential hazards. This comprehensive guide will provide detailed instructions on how to safely jump a car in the rain, ensuring both your ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin4 days ago - Can taxpayers be confident PIJF cash was spent wisely?

Graham Adams writes about the $55m media fund — When Patrick Gower was asked by Mike Hosking last week what he would say to the many Newstalk ZB callers who allege the Labour government bribed media with $55 million of taxpayers’ money via the Public Interest Journalism Fund — and ...Point of OrderBy gadams10005 days ago

Graham Adams writes about the $55m media fund — When Patrick Gower was asked by Mike Hosking last week what he would say to the many Newstalk ZB callers who allege the Labour government bribed media with $55 million of taxpayers’ money via the Public Interest Journalism Fund — and ...Point of OrderBy gadams10005 days ago

Related Posts

- Release: Budget blunder shows Nicola Willis could cut recovery funding

It appears Nicola Willis is about to pull the rug out from under the feet of local communities still dealing with the aftermath of last year’s severe weather, and local councils relying on funding to build back from these disasters. ...23 hours ago

It appears Nicola Willis is about to pull the rug out from under the feet of local communities still dealing with the aftermath of last year’s severe weather, and local councils relying on funding to build back from these disasters. ...23 hours ago - Further environmental mismanagement on the cards

The Government’s resource management reforms will add to the heavy and ever-growing burden this Government is loading on to our environment. ...1 day ago

The Government’s resource management reforms will add to the heavy and ever-growing burden this Government is loading on to our environment. ...1 day ago - Release: RMA changes will be a disaster for environment

The Government is making short-sighted changes to the Resource Management Act (RMA) that will take away environmental protection in favour of short-term profits, Labour’s environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said today. ...1 day ago

The Government is making short-sighted changes to the Resource Management Act (RMA) that will take away environmental protection in favour of short-term profits, Labour’s environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said today. ...1 day ago - Release: Labour supports urgent changes to emergency management system

Labour welcomes the release of the report into the North Island weather events and looks forward to working with the Government to ensure that New Zealand is as prepared as it can be for the next natural disaster. ...1 day ago

Labour welcomes the release of the report into the North Island weather events and looks forward to working with the Government to ensure that New Zealand is as prepared as it can be for the next natural disaster. ...1 day ago - Release: Labour calls for New Zealand to recognise Palestine

The Labour Party has called for the New Zealand Government to recognise Palestine, as a material step towards progressing the two-State solution needed to achieve a lasting peace in the region. ...2 days ago

The Labour Party has called for the New Zealand Government to recognise Palestine, as a material step towards progressing the two-State solution needed to achieve a lasting peace in the region. ...2 days ago - Release: Three strikes law political posturing of worst kind

The Government is bringing back a law that has little evidential backing just to look tough, Labour justice spokesperson Duncan Webb said. ...2 days ago

The Government is bringing back a law that has little evidential backing just to look tough, Labour justice spokesperson Duncan Webb said. ...2 days ago - Release: Government cuts unbelievably target child exploitation, violent extremism, ports and airpor...

Some of our country’s most important work, stopping the sexual exploitation of children and violent extremism could go along with staff on the frontline at ports and airports. ...2 days ago

Some of our country’s most important work, stopping the sexual exploitation of children and violent extremism could go along with staff on the frontline at ports and airports. ...2 days ago - Three strikes has failed before and will fail again

Resurrecting the archaic three-strikes legislation is an unwelcome return to a failed American-style approach to justice. ...2 days ago

Resurrecting the archaic three-strikes legislation is an unwelcome return to a failed American-style approach to justice. ...2 days ago - Release: Environmental protection vital, not ‘onerous’

The Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill will give projects such as new coal mines a ‘get out of jail free’ card to wreak havoc on the environment, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said today. ...2 days ago

The Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill will give projects such as new coal mines a ‘get out of jail free’ card to wreak havoc on the environment, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said today. ...2 days ago - Release: Govt cuts doctors and nurses in hiring freeze

Cuts to frontline hospital staff are not only a broken election promise, it shows the reckless tax cuts have well and truly hit the frontline of the health system, says Labour Health spokesperson Ayesha Verrall. ...5 days ago

Cuts to frontline hospital staff are not only a broken election promise, it shows the reckless tax cuts have well and truly hit the frontline of the health system, says Labour Health spokesperson Ayesha Verrall. ...5 days ago - Fast-track submissions period must be extended

The Green Party has joined the call for public submissions on the fast-track legislation to be extended after the Ombudsman forced the Government to release the list of organisations invited to apply just hours before submissions close. ...5 days ago

The Green Party has joined the call for public submissions on the fast-track legislation to be extended after the Ombudsman forced the Government to release the list of organisations invited to apply just hours before submissions close. ...5 days ago - Release: Progress on climate will be undone by Govt

New Zealand’s good work at reducing climate emissions for three years in a row will be undone by the National government’s lack of ambition and scrapping programmes that were making a difference, Labour Party climate spokesperson Megan Woods said today. ...5 days ago

New Zealand’s good work at reducing climate emissions for three years in a row will be undone by the National government’s lack of ambition and scrapping programmes that were making a difference, Labour Party climate spokesperson Megan Woods said today. ...5 days ago - Release: Dark day for Kiwi kids as a third of Govt cuts affect them

News that 1000 jobs at the Ministry of Education and Oranga Tamariki could go is devastating for future generations of New Zealanders. ...1 week ago

News that 1000 jobs at the Ministry of Education and Oranga Tamariki could go is devastating for future generations of New Zealanders. ...1 week ago - Release: Alarm as Government signals further blow to school lunches

More essential jobs could be on the chopping block, this time Ministry of Education staff on the school lunches team are set to find out whether they're in line to lose their jobs. ...1 week ago

More essential jobs could be on the chopping block, this time Ministry of Education staff on the school lunches team are set to find out whether they're in line to lose their jobs. ...1 week ago - Release: Quick, submit – stop Govt’s dodgy approvals bill

The Government is trying to bring in a law that will allow Ministers to cut corners and kill off native species, Labour environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said. ...1 week ago

The Government is trying to bring in a law that will allow Ministers to cut corners and kill off native species, Labour environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said. ...1 week ago - Government throws coal on the climate crisis fire

The Government’s policy announced today to ease consenting for coal mining will have a lasting impact across generations. ...1 week ago

The Government’s policy announced today to ease consenting for coal mining will have a lasting impact across generations. ...1 week ago - Release: Public transport costs to double as National looks at unaffordable roading project instead

Cancelling urgently needed new Cook Strait ferries and hiking the cost of public transport for many Kiwis so that National can announce the prospect of another tunnel for Wellington is not making good choices, Labour Transport Spokesperson Tangi Utikere said. ...1 week ago

Cancelling urgently needed new Cook Strait ferries and hiking the cost of public transport for many Kiwis so that National can announce the prospect of another tunnel for Wellington is not making good choices, Labour Transport Spokesperson Tangi Utikere said. ...1 week ago - Release: Cost of living in Auckland still not a priority

A laundry list of additional costs for Tāmaki Makarau Auckland shows the Minister for the city is not delivering for the people who live there, says Labour Auckland Issues spokesperson Shanan Halbert. ...1 week ago

A laundry list of additional costs for Tāmaki Makarau Auckland shows the Minister for the city is not delivering for the people who live there, says Labour Auckland Issues spokesperson Shanan Halbert. ...1 week ago - Greens look to fast-track submissions on harmful law

The Green Party has today launched a step-by-step guide to help New Zealanders make their voice heard on the Government’s democracy dodging and anti-environment fast track legislation. ...2 weeks ago

The Green Party has today launched a step-by-step guide to help New Zealanders make their voice heard on the Government’s democracy dodging and anti-environment fast track legislation. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Govt should stop making people’s lives harder and build more homes

The National Government’s proposed changes to the Residential Tenancies Act will mean tenants can be turfed from their homes by landlords with little notice, Labour housing spokesperson Kieran McAnulty said. ...2 weeks ago

The National Government’s proposed changes to the Residential Tenancies Act will mean tenants can be turfed from their homes by landlords with little notice, Labour housing spokesperson Kieran McAnulty said. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Melissa Lee missing in action on media

The action Melissa Lee promised to protect democracy and the media sector is missing, Media and Communications spokesperson Willie Jackson said. ...2 weeks ago

The action Melissa Lee promised to protect democracy and the media sector is missing, Media and Communications spokesperson Willie Jackson said. ...2 weeks ago - Landlord Government leaves little hope for renters2 weeks ago

- Opportunity to build a more sustainable economy

Green Party co-leader Marama Davidson is calling on all parties to support a common-sense change that’s great for the planet and great for consumers after her member’s bill was drawn from the ballot today. ...2 weeks ago

Green Party co-leader Marama Davidson is calling on all parties to support a common-sense change that’s great for the planet and great for consumers after her member’s bill was drawn from the ballot today. ...2 weeks ago - Significant step forward in fixing cruel and unjust past

A significant milestone has been reached in the fight to strike an anti-Pasifika and unfair law from the country’s books after Teanau Tuiono’s members’ bill passed its first reading. ...2 weeks ago

A significant milestone has been reached in the fight to strike an anti-Pasifika and unfair law from the country’s books after Teanau Tuiono’s members’ bill passed its first reading. ...2 weeks ago - Missed opportunity but NZ will surely one day recognise the right to a sustainable environment

New Zealand has today missed the opportunity to uphold the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, says James Shaw after his member’s bill was voted down in its first reading. ...2 weeks ago

New Zealand has today missed the opportunity to uphold the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, says James Shaw after his member’s bill was voted down in its first reading. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Don’t cut our lunches – clear message sent to Government

Tens of thousands of people are demanding the Government commits to fully funding free and healthy school lunches. ...2 weeks ago

Tens of thousands of people are demanding the Government commits to fully funding free and healthy school lunches. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Govt makes U-turn on Suicide Prevention Office

Labour welcomes the Government’s U-turn on the closure of the Suicide Prevention Office, says Labour Mental Health spokesperson Ingrid Leary. ...2 weeks ago

Labour welcomes the Government’s U-turn on the closure of the Suicide Prevention Office, says Labour Mental Health spokesperson Ingrid Leary. ...2 weeks ago - CCC issues warning over further climate delay

Today’s advice from the Climate Change Commission paints a sobering reality of the challenge we face in combating climate change, especially in light of recent Government policy announcements. ...2 weeks ago

Today’s advice from the Climate Change Commission paints a sobering reality of the challenge we face in combating climate change, especially in light of recent Government policy announcements. ...2 weeks ago - Luxon targets lame and lousy example of leadership2 weeks ago

- Luxon targets are lousy example of leadership2 weeks ago

- Release: Commitment to disability communities missing from Govt priorities

Minister for Disability Issues Penny Simmonds appears to have delayed a report back to Cabinet on the progress New Zealand is making against international obligations for disabled New Zealanders. ...2 weeks ago

Minister for Disability Issues Penny Simmonds appears to have delayed a report back to Cabinet on the progress New Zealand is making against international obligations for disabled New Zealanders. ...2 weeks ago - Methane target review is dangerous duplication

The Government’s newly announced review of methane emissions reduction targets hints at its desire to delay Aotearoa New Zealand’s urgent transition to a climate safe future, the Green Party said. ...3 weeks ago

The Government’s newly announced review of methane emissions reduction targets hints at its desire to delay Aotearoa New Zealand’s urgent transition to a climate safe future, the Green Party said. ...3 weeks ago - Release: Government must commit to school building project for disabled students

The Government must commit to the Maitai School building project for students with high and complex needs, to ensure disabled students from the top of the South Island have somewhere to learn. ...3 weeks ago

The Government must commit to the Maitai School building project for students with high and complex needs, to ensure disabled students from the top of the South Island have somewhere to learn. ...3 weeks ago - Release: National must take mental health seriously

Mental Health Minister Matt Doocey and his Government colleagues have made a meal of their mental health commitments, showing how flimsy their efforts to champion the issue truly are, says Labour Mental Health spokesperson Ingrid Leary. ...3 weeks ago

Mental Health Minister Matt Doocey and his Government colleagues have made a meal of their mental health commitments, showing how flimsy their efforts to champion the issue truly are, says Labour Mental Health spokesperson Ingrid Leary. ...3 weeks ago - Referendums for Māori wards a racist step backwards

The Government's imposed referendum on Māori wards is a racist step backwards for Māori representation, and disregards Te Tiriti o Waitangi. ...3 weeks ago

The Government's imposed referendum on Māori wards is a racist step backwards for Māori representation, and disregards Te Tiriti o Waitangi. ...3 weeks ago - Release: Job losses at Health not worth it for tax cuts

New Zealand will feel the harm of the National Government’s reckless cuts to jobs at the health ministry for generations, says Ayesha Verrall. ...3 weeks ago

New Zealand will feel the harm of the National Government’s reckless cuts to jobs at the health ministry for generations, says Ayesha Verrall. ...3 weeks ago

Related Posts

- PM announces changes to portfolios

Paul Goldsmith will take on responsibility for the Media and Communications portfolio, while Louise Upston will pick up the Disability Issues portfolio, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon announced today. “Our Government is relentlessly focused on getting New Zealand back on track. As issues change in prominence, I plan to adjust Ministerial ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz3 hours ago

Paul Goldsmith will take on responsibility for the Media and Communications portfolio, while Louise Upston will pick up the Disability Issues portfolio, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon announced today. “Our Government is relentlessly focused on getting New Zealand back on track. As issues change in prominence, I plan to adjust Ministerial ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz3 hours ago - New catch limits for unique fishery areas

Recreational catch limits will be reduced in areas of Fiordland and the Chatham Islands to help keep those fisheries healthy and sustainable, Oceans and Fisheries Minister Shane Jones says. The lower recreational daily catch limits for a range of finfish and shellfish species caught in the Fiordland Marine Area and ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 hours ago

Recreational catch limits will be reduced in areas of Fiordland and the Chatham Islands to help keep those fisheries healthy and sustainable, Oceans and Fisheries Minister Shane Jones says. The lower recreational daily catch limits for a range of finfish and shellfish species caught in the Fiordland Marine Area and ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 hours ago - Minister welcomes hydrogen milestone