Beyond Left and Right?

Beyond Left and Right?

Written By:

te reo putake - Date published:

8:27 pm, September 17th, 2018 - 78 comments

Categories: capitalism, class war, Economy, Media, Politics, poverty, Social issues, socialism, workers' rights -

Tags: class, class warfare, karl marx

I had an interesting discussion the other day with a regular TS contributor. The subject and substance of the exchange is not what brings me to write this post, so I’m going to skip the details. It was the commenter’s use of information from right wing websites to justify left wing positions that got me curious.

I have a sneaking suspicion that many people whose political and social instincts are solidly left wing have no idea what the term means. They may have heart, they may have a sense that the world is unfair, however they lack class understanding and therefore have no effective bullshit meter.

And not having a grounding in working class politics means that any old tosh that sounds anti-establishment gets a pass mark whether it’s deserved or not. Forget fake news, fake views are what we really have to worry about.

And it logically follows from that position that those folk will never really know what’s going on and will always be susceptible to being suckered.

Let’s be crystal clear. The Government is not the real problem, it’s capitalism. It’s not chem trails, buildings in free fall or 1080. It’s capitalism. It’s not virtue signalling, putting preferred pronouns on Twitter pages or overusing the epiphet ‘racist!’. It’s capitalism.

It’s always capitalism.

Now, I don’t mean that earlier analysis in a nasty way; I’m not saying that people who’ve never read Marx, Lenin, Dimitrov, Luxemburg and so many others are foolish or stupid people, just that they are ignorant of what defines the left.

And it’s not easy getting that learning. For a start, you’ll have to read books. So that’s the men out of this discussion already. See how hard it is?

No point blaming the news gathering media for our collective ignorance either. Removing sub editors means that there is simply no quality control any more. Newspapers used to have the piss taken out of them if they occasionally misspelled words, but nowadays there is a budget for accidental defamation roughly equivalent to the salaries saved when all the wielders of the blue pencil were made redundant.

And it’s not a red pill/blue pill choice. That’s a fantasy designed to stroke teenage egos. What’s going on is a class struggle and you, dear reader, are part of it, because we’re all working class these days and have been for nearly four decades.

There’s no middle class any more. There’s just different degrees of poverty, from outright destitution to the mirage of credit card and house price wealth.

So what’s stopping us from uniting and losing our chains?

“The Democrats, the longer they talk about identity politics, I got ’em. I want them to talk about racism every day. If the left is focused on race and identity, and we go with economic nationalism, we can crush the Democrats.”

That’s Steve Bannon, quoted in the halcyon days when he was re-setting the White House agenda.

Steve gets it. He knows it’s a class struggle, it’s just that his class isn’t your class.

The author of the seminal book The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama, has been reassessing his tome. Back in the eighties, Fukuyama suggested liberalism was probably humanity’s end state. Looking back, he now recognises that the triumph of liberalism over fascism and communism has not ended the world’s problems, nor has it bought any kind of societal consensus.

Fukuyama now notes:

“You have leftwing and rightwing versions of identity politics. The leftwing version is longer-standing, where different social movements began to emphasise the ways they were different from mainstream culture and that they needed respect in various ways. And then there was a reaction on the right, from people who thought, ‘Well, what about us? Why don’t we qualify for special treatment as well?’

Politically, it is problematic in that it undermines a sense of citizenship. And now you get extremism on both sides.”

It’s that sense of citizenship that I really miss. We’re all citizens, but we don’t see it as something to be exercised, something to work on. Something to be part of.

Cui bono, readers, cui fucken bono?

I have a question, once posed to a law class I was taking, that has always stuck in my mind as a useful indicator of class understanding:

What’s more important, individual rights or collective rights?

So what do you think the answer to that question is, Standarnistas?

And why does it matter?

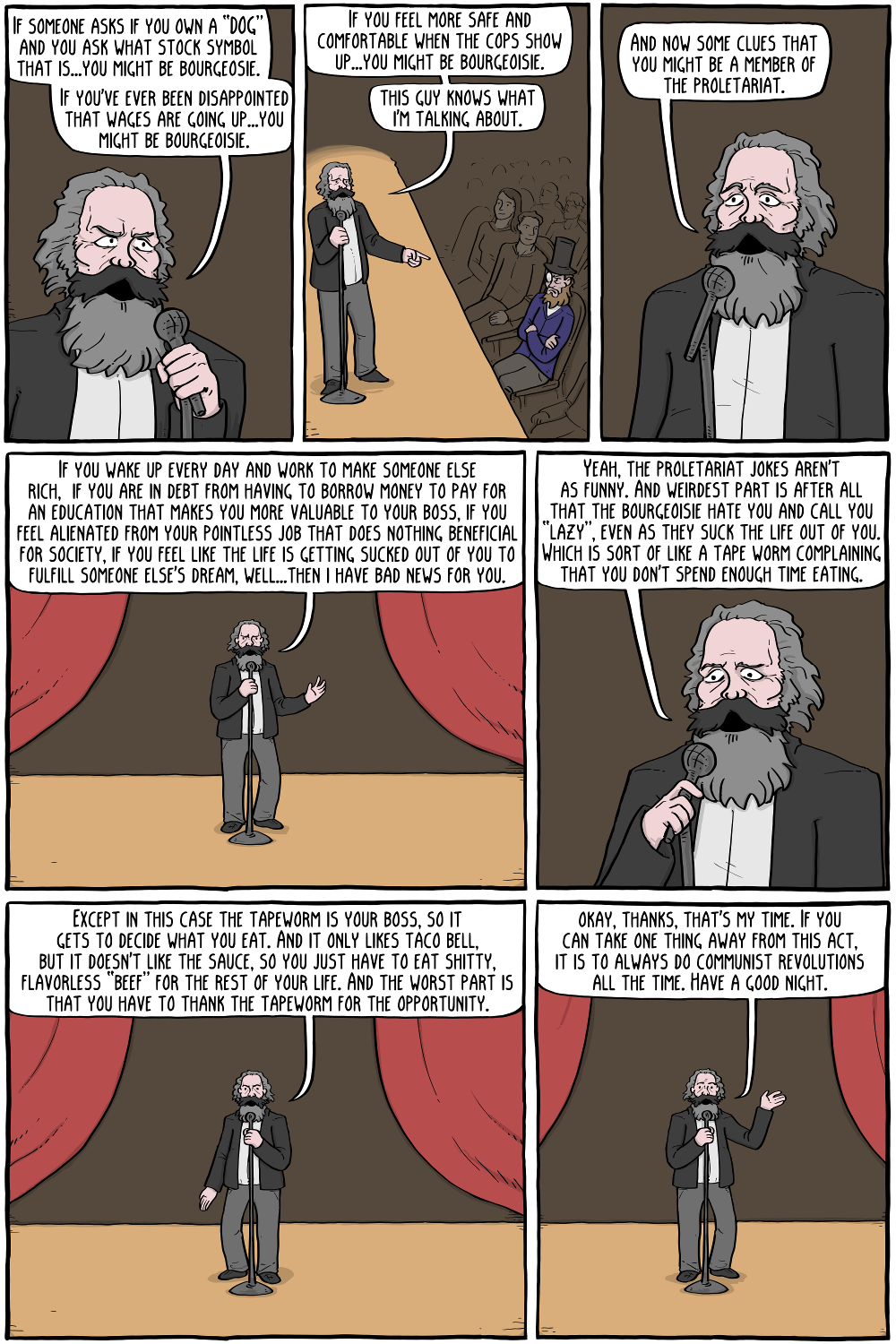

KARL MARX as stand up comedian:

Related Posts

78 comments on “Beyond Left and Right? ”

- Comments are now closed

- Comments are now closed

Recent Comments

- SPC on

- Incognito to Patricia Bremner on

- joe90 on

- joe90 on

- Incognito on

- Cricklewood to Ad on

- Stephen D on

- joe90 on

- SPC on

- joe90 on

- weka to Patricia Bremner on

- tc to Patricia Bremner on

- lprent to Bearded Git on

- lprent to Bearded Git on

- joe90 to Bearded Git on

- Bearded Git to KJT on

- Bearded Git to lprent on

- KJT on

- Bearded Git on

- joe90 on

- Bearded Git on

- Ad on

- Macro on

- weka to Obtrectator on

- weka on

Recent Posts

-

by lprent

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by Incognito

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by advantage

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

-

by lprent

-

by weka

-

by advantage

-

by Guest post

-

by Incognito

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Guest post

-

by Guest post

-

by advantage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

- Whatever the CCP says, regimes don’t have the rights of nations

All nation states have a right to defend themselves. But do regimes enjoy an equal right to self-defence? Is the security of a particular party-in-power a fundamental right of nations? The Chinese government is asking ...The StrategistBy John Fitzgerald7 hours ago

All nation states have a right to defend themselves. But do regimes enjoy an equal right to self-defence? Is the security of a particular party-in-power a fundamental right of nations? The Chinese government is asking ...The StrategistBy John Fitzgerald7 hours ago - Countervailing Trumpian Sense

A modest attempt to analyse Donald Trump’s tariff policies.Alfred Marshall, whose text book was still in use 40 years after he died wrote ‘every short statement about economics is misleading with the possible exception of my present one.’ (The text book is 719 pages.) It’s a timely reminder that any ...PunditBy Brian Easton7 hours ago

A modest attempt to analyse Donald Trump’s tariff policies.Alfred Marshall, whose text book was still in use 40 years after he died wrote ‘every short statement about economics is misleading with the possible exception of my present one.’ (The text book is 719 pages.) It’s a timely reminder that any ...PunditBy Brian Easton7 hours ago - Uncertainty, Hierarchy and the Dilemma of Democracy.

If nothing else, we have learned that the economic and geopolitical turmoil caused by the Trump tariff see-saw raises a fundamental issue of the human condition that extends beyond trade wars and “the markets.” That issue is uncertainty and its centrality to individual and collective life. It extends further into ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo7 hours ago

If nothing else, we have learned that the economic and geopolitical turmoil caused by the Trump tariff see-saw raises a fundamental issue of the human condition that extends beyond trade wars and “the markets.” That issue is uncertainty and its centrality to individual and collective life. It extends further into ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo7 hours ago - Strengthening South Korea’s national security by adopting the cloud

To improve its national security, South Korea must improve its ICT infrastructure. Knowing this, the government has begun to move towards cloud computing. The public and private sectors are now taking a holistic national-security approach ...The StrategistBy Afeeya Akhand8 hours ago

To improve its national security, South Korea must improve its ICT infrastructure. Knowing this, the government has begun to move towards cloud computing. The public and private sectors are now taking a holistic national-security approach ...The StrategistBy Afeeya Akhand8 hours ago - Workers’ Memorial Day 2025

28 April 2025 Mournfor theDead FightFor theLiving Every week in New Zealand 18 workers are killed as a consequence of work. Every 15 minutes, a worker suffers ...NZCTUBy Jeremiah Boniface9 hours ago

28 April 2025 Mournfor theDead FightFor theLiving Every week in New Zealand 18 workers are killed as a consequence of work. Every 15 minutes, a worker suffers ...NZCTUBy Jeremiah Boniface9 hours ago - Reset Pax Americana: the West needs a grand accord

The world is trying to make sense of the Trump tariffs. Is there a grand design and strategy, or is it all instinct and improvisation? But much more important is the question of what will ...The StrategistBy Michael Pezzullo11 hours ago

The world is trying to make sense of the Trump tariffs. Is there a grand design and strategy, or is it all instinct and improvisation? But much more important is the question of what will ...The StrategistBy Michael Pezzullo11 hours ago - Poisoning The Well – It’s Not Just ACT

OPINION:Yesterday was a triumphant moment in Parliament House.The “divisive”, “disingenous”, “unfair”, “discriminatory” and “dishonest” Treaty Principles Bill, advanced by the right wing ACT Party, failed.Spectacularly.11 MP votes for (ACT).112 MP votes against (All Other Parties).As the wonderful Te Pāti Māori MP, Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke said: We are not divided, but united.Green ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī12 hours ago

OPINION:Yesterday was a triumphant moment in Parliament House.The “divisive”, “disingenous”, “unfair”, “discriminatory” and “dishonest” Treaty Principles Bill, advanced by the right wing ACT Party, failed.Spectacularly.11 MP votes for (ACT).112 MP votes against (All Other Parties).As the wonderful Te Pāti Māori MP, Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke said: We are not divided, but united.Green ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī12 hours ago - The Pacific Response Group is making pleasing progress but needs more buy-in

The Pacific Response Group (PRG), a new disaster coordination organisation, has operated through its first high-risk weather season. But as representatives from each Pacific military leave Brisbane to return to their home countries for the ...The StrategistBy Blake Johnson and Adam Ziogas13 hours ago

The Pacific Response Group (PRG), a new disaster coordination organisation, has operated through its first high-risk weather season. But as representatives from each Pacific military leave Brisbane to return to their home countries for the ...The StrategistBy Blake Johnson and Adam Ziogas13 hours ago - Friday 11 April

The Treaty Principles Bill has been defeated in Parliament with 112 votes in opposition and 11 in favour, but the debate about Te Tiriti and Māori rights looks set to stay high on the political agenda. Supermarket giant Woolworths has confirmed a new operating model that Workers First say will ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald14 hours ago

The Treaty Principles Bill has been defeated in Parliament with 112 votes in opposition and 11 in favour, but the debate about Te Tiriti and Māori rights looks set to stay high on the political agenda. Supermarket giant Woolworths has confirmed a new operating model that Workers First say will ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald14 hours ago - A few wins, for now

More Than A FeildingBy David Slack15 hours ago

- Aotearoa Wins!

And this is what I'm gonna doI'm gonna put a call to you'Cause I feel good tonightAnd everything's gonna beRight-right-rightI'm gonna have a good time tonightRock and roll music gonna play all nightCome on, baby, it won't take longOnly take a minute just to sing my songSongwriters: Kirk Pengilly / ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel15 hours ago

And this is what I'm gonna doI'm gonna put a call to you'Cause I feel good tonightAnd everything's gonna beRight-right-rightI'm gonna have a good time tonightRock and roll music gonna play all nightCome on, baby, it won't take longOnly take a minute just to sing my songSongwriters: Kirk Pengilly / ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel15 hours ago - Indonesia’s cyber soldiers: armed without a compass

The Indonesian military has a new role in cybersecurity but, worryingly, no clear doctrine on what to do with it nor safeguards against human rights abuses. Assignment of cyber responsibility to the military is part ...The StrategistBy Gatra Priyandita and Christian Guntur Lebang16 hours ago

The Indonesian military has a new role in cybersecurity but, worryingly, no clear doctrine on what to do with it nor safeguards against human rights abuses. Assignment of cyber responsibility to the military is part ...The StrategistBy Gatra Priyandita and Christian Guntur Lebang16 hours ago - Weekly Roundup 11-April-2025

Another Friday, another roundup. Autumn is starting to set in, certainly getting darker earlier but we hope you enjoy some of the stories we found interesting this week. This week in Greater Auckland On Tuesday we ran a guest post from the wonderful Darren Davis about what’s happening ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland16 hours ago

Another Friday, another roundup. Autumn is starting to set in, certainly getting darker earlier but we hope you enjoy some of the stories we found interesting this week. This week in Greater Auckland On Tuesday we ran a guest post from the wonderful Darren Davis about what’s happening ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland16 hours ago - Bernard’s Dawn Chorus & Pick ‘n’ Mix Six for Friday, April 11

Long stories shortest: The White House confirms Donald Trump’s total tariffs now on China are 145%, not 125%. US stocks slump again. Gold hits a record high. PM Christopher Luxon joins a push for a new rules-based trading system based around CPTPP and EU, rather than US-led WTO. Winston Peters ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey17 hours ago

Long stories shortest: The White House confirms Donald Trump’s total tariffs now on China are 145%, not 125%. US stocks slump again. Gold hits a record high. PM Christopher Luxon joins a push for a new rules-based trading system based around CPTPP and EU, rather than US-led WTO. Winston Peters ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey17 hours ago - The Hoon around the week to April 11

The podcast above of the weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers on Thursday night features co-hosts & talking about the week’s news with regular and special guests, including: and on the week in geopolitics and climate, including Donald Trump’s shock and (partial) backflip; and,Health Coalition Aotearoa Chair ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey18 hours ago

The podcast above of the weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers on Thursday night features co-hosts & talking about the week’s news with regular and special guests, including: and on the week in geopolitics and climate, including Donald Trump’s shock and (partial) backflip; and,Health Coalition Aotearoa Chair ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey18 hours ago - Skeptical Science New Research for Week #15 2025

Open access notables Global and regional drivers for exceptional climate extremes in 2023-2024: beyond the new normal, Minobe et al., npj Climate and Atmospheric Science: Climate records have been broken with alarming regularity in recent years, but the events of 2023–2024 were exceptional even when accounting for recent climatic trends. ...1 day ago

Open access notables Global and regional drivers for exceptional climate extremes in 2023-2024: beyond the new normal, Minobe et al., npj Climate and Atmospheric Science: Climate records have been broken with alarming regularity in recent years, but the events of 2023–2024 were exceptional even when accounting for recent climatic trends. ...1 day ago - The US harms its image in the Pacific with aid cuts and tariffs

USAID cuts and tariffs will harm the United States’ reputation in the Pacific more than they will harm the region itself. The resilient region will adjust to the economic challenges and other partners will fill ...The StrategistBy Blake Johnson and Astrid Young1 day ago

USAID cuts and tariffs will harm the United States’ reputation in the Pacific more than they will harm the region itself. The resilient region will adjust to the economic challenges and other partners will fill ...The StrategistBy Blake Johnson and Astrid Young1 day ago - Good fucking riddance

National's racist and divisive Treaty Principles Bill was just voted down by the House, 112 to 11. Good fucking riddance. The bill was not a good-faith effort at legislating, or at starting a "constitutional conversation". Instead it was a bad faith attempt to stoke division and incite racial hatred - ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 day ago

National's racist and divisive Treaty Principles Bill was just voted down by the House, 112 to 11. Good fucking riddance. The bill was not a good-faith effort at legislating, or at starting a "constitutional conversation". Instead it was a bad faith attempt to stoke division and incite racial hatred - ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 day ago - The threat spectrum

Democracy watch Indonesia’s parliament passed revisions to the country’s military law, which pro-democracy and human rights groups view as a threat to the country’s democracy. One of the revisions seeks to expand the number of ...The StrategistBy Linus Cohen, Astrid Young and Alice Wai1 day ago

Democracy watch Indonesia’s parliament passed revisions to the country’s military law, which pro-democracy and human rights groups view as a threat to the country’s democracy. One of the revisions seeks to expand the number of ...The StrategistBy Linus Cohen, Astrid Young and Alice Wai1 day ago - Australia needs a civilian cyber reserve. State emergency services are the model

Australia should follow international examples and develop a civilian cyber reserve as part of a whole-of-society approach to national defence. By setting up such a reserve, the federal government can overcome a shortage of expertise ...The StrategistBy Samuli Haataja and Dan Svantesson1 day ago

Australia should follow international examples and develop a civilian cyber reserve as part of a whole-of-society approach to national defence. By setting up such a reserve, the federal government can overcome a shortage of expertise ...The StrategistBy Samuli Haataja and Dan Svantesson1 day ago - Drawn

A ballot for three Member's Bills was held today, and the following bills were drawn: Life Jackets for Children and Young Persons Bill (Cameron Brewer) Sale and Supply of Alcohol (Restrictions on Issue of Off-Licences and Low and No Alcohol Products) Amendment Bill (Mike Butterick) Crown ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago

A ballot for three Member's Bills was held today, and the following bills were drawn: Life Jackets for Children and Young Persons Bill (Cameron Brewer) Sale and Supply of Alcohol (Restrictions on Issue of Off-Licences and Low and No Alcohol Products) Amendment Bill (Mike Butterick) Crown ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago - Thursday 10 April

Te Whatu Ora is proposing to slash jobs from a department that brings in millions of dollars a year and ensures safety in hospitals, rest homes and other community health providers. The Treaty Principles Bill is back in Parliament this evening and is expected to be voted down by all parties, ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago

Te Whatu Ora is proposing to slash jobs from a department that brings in millions of dollars a year and ensures safety in hospitals, rest homes and other community health providers. The Treaty Principles Bill is back in Parliament this evening and is expected to be voted down by all parties, ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago - Paying For Small Indignities

Hi,The piece I wrote last week about the chances of being rounded up and evicted (and/or detained) by the United States seems more… pressing.To be clear: antisemitism is fucking horrible — and in that same breath I also wonder what today’s statement from The Department of Homeland security means for ...David FarrierBy David Farrier2 days ago

Hi,The piece I wrote last week about the chances of being rounded up and evicted (and/or detained) by the United States seems more… pressing.To be clear: antisemitism is fucking horrible — and in that same breath I also wonder what today’s statement from The Department of Homeland security means for ...David FarrierBy David Farrier2 days ago - Joint naval exercises with Russia undermine Indonesia’s commitment to international law

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto has repeatedly asserted the country’s commitment to a non-aligned foreign policy. But can Indonesia still credibly claim neutrality while tacitly engaging with Russia? Holding an unprecedented bilateral naval drills with Moscow ...The StrategistBy Darul Mahdi2 days ago

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto has repeatedly asserted the country’s commitment to a non-aligned foreign policy. But can Indonesia still credibly claim neutrality while tacitly engaging with Russia? Holding an unprecedented bilateral naval drills with Moscow ...The StrategistBy Darul Mahdi2 days ago - Wednesday 9 April

The NZCTU have launched a new policy programme and are calling on political parties to adopt bold policies in the lead up to the next election. The Government is scrapping the 30-day rule that automatically signs an employee up to the collective agreement when they sign on to a new ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago

The NZCTU have launched a new policy programme and are calling on political parties to adopt bold policies in the lead up to the next election. The Government is scrapping the 30-day rule that automatically signs an employee up to the collective agreement when they sign on to a new ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago - Anticipating what Trump wants: Taiwan puts money in America first

Taiwan’s President Lai Ching-te must have been on his toes. The island’s trade and defence policy has snapped into a new direction since US President Donald Trump took office in January. The government was almost ...The StrategistBy Jane Rickards2 days ago

Taiwan’s President Lai Ching-te must have been on his toes. The island’s trade and defence policy has snapped into a new direction since US President Donald Trump took office in January. The government was almost ...The StrategistBy Jane Rickards2 days ago - Auckland’s Big Easter Rail Shutdown

Auckland’s ongoing rail pain will intensify again from this weekend as Kiwirail shut down the network for two weeks as part of their push to get the network ready for the City Rail Link. KiwiRail will progress upgrade and renewal projects across Auckland’s rail network over the Easter holiday period ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L2 days ago

Auckland’s ongoing rail pain will intensify again from this weekend as Kiwirail shut down the network for two weeks as part of their push to get the network ready for the City Rail Link. KiwiRail will progress upgrade and renewal projects across Auckland’s rail network over the Easter holiday period ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L2 days ago - Renewables allow us to pay less, not twice

This is a re-post from The Electrotech Revolution by Daan Walter Last week, UK Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch took the stage to advocate for slowing the rollout of renewables, arguing that they ultimately lead to higher costs: “Huge amounts are being spent on switching round how we distribute electricity ...2 days ago

This is a re-post from The Electrotech Revolution by Daan Walter Last week, UK Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch took the stage to advocate for slowing the rollout of renewables, arguing that they ultimately lead to higher costs: “Huge amounts are being spent on switching round how we distribute electricity ...2 days ago - Refusing to Disappear

That there, that's not meI go where I pleaseI walk through wallsI float down the LiffeyI'm not hereThis isn't happeningI'm not hereI'm not hereSongwriters: Philip James Selway / Jonathan Richard Guy Greenwood / Edward John O'Brien / Thomas Edward Yorke / Colin Charles Greenwood.I had mixed views when the first ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago

That there, that's not meI go where I pleaseI walk through wallsI float down the LiffeyI'm not hereThis isn't happeningI'm not hereI'm not hereSongwriters: Philip James Selway / Jonathan Richard Guy Greenwood / Edward John O'Brien / Thomas Edward Yorke / Colin Charles Greenwood.I had mixed views when the first ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago - Bernard’s Dawn Chorus & Pick ‘n’ Mix Six

(A note to subscribers: I’m going to keep these daily curated news updates shorter in future to ensure an earlier and more regular delivery. Expect this format and delivery around 7 am Monday to Friday from now on. My apologies for not delivering yesterday. There was too much news… This ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

(A note to subscribers: I’m going to keep these daily curated news updates shorter in future to ensure an earlier and more regular delivery. Expect this format and delivery around 7 am Monday to Friday from now on. My apologies for not delivering yesterday. There was too much news… This ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - Gordon Campbell On Marketing The Military Threat Posed By China

As Donald Trump zigs and zags on tariffs and trashes America’s reputation as a safe and stable place to invest, China has a big gun that it could bring to this tariff knife fight. Behind Japan, China has the world’s second largest holdings of American debt. As a huge US ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor2 days ago

As Donald Trump zigs and zags on tariffs and trashes America’s reputation as a safe and stable place to invest, China has a big gun that it could bring to this tariff knife fight. Behind Japan, China has the world’s second largest holdings of American debt. As a huge US ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor2 days ago - Seabed sensors and mapping: what China’s survey ship could be up to

Civilian exploration may be the official mission of a Chinese deep-sea research ship that sailed clockwise around Australia over the past week and is now loitering west of the continent. But maybe it’s also attending ...The StrategistBy Euan Graham and Ray Powell2 days ago

Civilian exploration may be the official mission of a Chinese deep-sea research ship that sailed clockwise around Australia over the past week and is now loitering west of the continent. But maybe it’s also attending ...The StrategistBy Euan Graham and Ray Powell2 days ago - South Korea must move beyond partisan division to tackle security threats

South Korea’s internal political instability leaves it vulnerable to rising security threats including North Korea’s military alliance with Russia, China’s growing regional influence and the United States’ unpredictability under President Donald Trump. South Korea needs ...The StrategistBy Kunwoo Kim2 days ago

South Korea’s internal political instability leaves it vulnerable to rising security threats including North Korea’s military alliance with Russia, China’s growing regional influence and the United States’ unpredictability under President Donald Trump. South Korea needs ...The StrategistBy Kunwoo Kim2 days ago - Billionaire Bust-Ups

Here are 5 updates that you may be interested in today:Speed kills and costs - so why does National want more of it?James (Jim) Grenon Board Takeover Gets Shaky - As Canadian Calls An Australian Shareholder a “Flake” Billionaire Bust-ups -The World’s Richest Men Are UncomfortableOver 3,500 Australian doctors on ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī2 days ago

Here are 5 updates that you may be interested in today:Speed kills and costs - so why does National want more of it?James (Jim) Grenon Board Takeover Gets Shaky - As Canadian Calls An Australian Shareholder a “Flake” Billionaire Bust-ups -The World’s Richest Men Are UncomfortableOver 3,500 Australian doctors on ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī2 days ago - Member’s Day

Today is a Member's Day, and its all first readings. First up is Laura McClure's Employment Relations (Termination of Employment by Agreement) Amendment Bill, followed by Carl Bates' Juries (Age of Excusal) Amendment Bill, Adrian Rurawhe's Employment Relations (Collective Agreements in Triangular Relationships) Amendment Bill and then Kieran McAnulty's Sale ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago

Today is a Member's Day, and its all first readings. First up is Laura McClure's Employment Relations (Termination of Employment by Agreement) Amendment Bill, followed by Carl Bates' Juries (Age of Excusal) Amendment Bill, Adrian Rurawhe's Employment Relations (Collective Agreements in Triangular Relationships) Amendment Bill and then Kieran McAnulty's Sale ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago - Australia’s cyber strategy needs a vulnerability disclosure upgrade

Australia is in a race against time. Cyber adversaries are exploiting vulnerabilities faster than we can identify and patch them. Both national security and economic considerations demand policy action. According to IBM’s Data Breach Report, ...The StrategistBy Adam Dobell and Ilona Cohen2 days ago

Australia is in a race against time. Cyber adversaries are exploiting vulnerabilities faster than we can identify and patch them. Both national security and economic considerations demand policy action. According to IBM’s Data Breach Report, ...The StrategistBy Adam Dobell and Ilona Cohen2 days ago - The Comparative Notebook on Trump’s Tariffs.

The ever brilliant Kate Nicholls has kindly agreed to allow me to re-publish her substack offering some under-examined backdrop to Trump’s tariff madness. The essay is not meant to be a full scholarly article but instead an insight into the thinking (if that is the correct word) behind the current ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo2 days ago

The ever brilliant Kate Nicholls has kindly agreed to allow me to re-publish her substack offering some under-examined backdrop to Trump’s tariff madness. The essay is not meant to be a full scholarly article but instead an insight into the thinking (if that is the correct word) behind the current ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo2 days ago - Humanitarian assistance in the Pacific should be led by Pacific countries

In the Pacific, the rush among partner countries to be seen as the first to assist after disasters has become heated as part of ongoing geopolitical contest. As partners compete for strategic influence in the ...The StrategistBy Miranda Booth, Henrietta McNeill and Genevieve Quirk3 days ago

In the Pacific, the rush among partner countries to be seen as the first to assist after disasters has become heated as part of ongoing geopolitical contest. As partners compete for strategic influence in the ...The StrategistBy Miranda Booth, Henrietta McNeill and Genevieve Quirk3 days ago - Tariff madness and monetary policy

We’ve seen this morning the latest step up in the Trump-initiated trade war, with the additional 50 per cent tariffs imposed on imports from China. If the tariff madness persists – but in fact even if were wound back in some places (eg some of the particularly absurd tariffs on ...Croaking CassandraBy Michael Reddell3 days ago

We’ve seen this morning the latest step up in the Trump-initiated trade war, with the additional 50 per cent tariffs imposed on imports from China. If the tariff madness persists – but in fact even if were wound back in some places (eg some of the particularly absurd tariffs on ...Croaking CassandraBy Michael Reddell3 days ago - Weak

Weak as I am, no tears for youWeak as I am, no tears for youDeep as I am, I'm no one's foolWeak as I amSongwriters: Deborah Ann Dyer / Richard Keith Lewis / Martin Ivor Kent / Robert Arnold FranceMorena.

Weak as I am, no tears for youWeak as I am, no tears for youDeep as I am, I'm no one's foolWeak as I amSongwriters: Deborah Ann Dyer / Richard Keith Lewis / Martin Ivor Kent / Robert Arnold FranceMorena.This morning, I couldn’t settle on a single topic. Too ...

Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago - Getting Cross with AT’s awful last minute re-designs of Project K

A few weeks ago, I wrote a post extensively detailing the scandal of what happened with the Upper Mercury Lane part of the Karanga-a-Hape Station precinct integration project (also known by its cool title, Project K). It was a prime example of Auckland Transport’s habitual failure to follow through on ...Greater AucklandBy Connor Sharp3 days ago

A few weeks ago, I wrote a post extensively detailing the scandal of what happened with the Upper Mercury Lane part of the Karanga-a-Hape Station precinct integration project (also known by its cool title, Project K). It was a prime example of Auckland Transport’s habitual failure to follow through on ...Greater AucklandBy Connor Sharp3 days ago - Climate risks to security in the Indo-Pacific: Indonesia in 2035

Australian policy makers are vastly underestimating how climate change will disrupt national security and regional stability across the Indo-Pacific. A new ASPI report assesses the ways climate impacts could threaten Indonesia’s economic and security interests ...The StrategistBy Mike Copage3 days ago

Australian policy makers are vastly underestimating how climate change will disrupt national security and regional stability across the Indo-Pacific. A new ASPI report assesses the ways climate impacts could threaten Indonesia’s economic and security interests ...The StrategistBy Mike Copage3 days ago - Brace position

So here we are in London again because we’re now at the do-it-while-you-still-can stage of life. More warm wide-armed hugs, more long talks and long walks and drinks in lovely old pubs with our lovely daughter.And meanwhile the world is once more in one of its assume-the-brace-position stages.We turned on ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago

So here we are in London again because we’re now at the do-it-while-you-still-can stage of life. More warm wide-armed hugs, more long talks and long walks and drinks in lovely old pubs with our lovely daughter.And meanwhile the world is once more in one of its assume-the-brace-position stages.We turned on ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago - To Dire Wolf Or Not To Dire Wolf?

Hi,Back in September of 2023, I got pitched an interview:David -Thanks for the quick response to the DM! Means the world. Re-stating some of the DM below for your team’s reference -I run a business called Animal Capital - we are a venture capital fund advised by Noah Beck, Paris ...David FarrierBy David Farrier3 days ago

Hi,Back in September of 2023, I got pitched an interview:David -Thanks for the quick response to the DM! Means the world. Re-stating some of the DM below for your team’s reference -I run a business called Animal Capital - we are a venture capital fund advised by Noah Beck, Paris ...David FarrierBy David Farrier3 days ago - A Bit Of Nuance Would Be Nice: Some Thoughts on the Trump Tariffs

I didn’t want to write about this – but, alas, the 2020s have forced my hand. I am going to talk about the Trump Tariffs… and in the process probably irritate nearly everyone. You see, alone on the Internet, I am one of those people who think we need a ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2213 days ago

I didn’t want to write about this – but, alas, the 2020s have forced my hand. I am going to talk about the Trump Tariffs… and in the process probably irritate nearly everyone. You see, alone on the Internet, I am one of those people who think we need a ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2213 days ago - No, it’s not new. Russia and China have been best buddies for decades

Maybe people are only just beginning to notice the close alignment of Russia and China. It’s discussed as a sudden new phenomenon in world affairs, but in fact it’s not new at all. The two ...The StrategistBy Sense Hofstede3 days ago

Maybe people are only just beginning to notice the close alignment of Russia and China. It’s discussed as a sudden new phenomenon in world affairs, but in fact it’s not new at all. The two ...The StrategistBy Sense Hofstede3 days ago - The dishonest crown

The High Court has just ruled that the government has been violating one of the oldest Treaty settlements, the Sealord deal: The High Court has found the Crown has breached one of New Zealand's oldest Treaty Settlements by appropriating Māori fishing quota without compensation. It relates to the 1992 ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago

The High Court has just ruled that the government has been violating one of the oldest Treaty settlements, the Sealord deal: The High Court has found the Crown has breached one of New Zealand's oldest Treaty Settlements by appropriating Māori fishing quota without compensation. It relates to the 1992 ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago - Middle Arm project: the infrastructure enabler for Northern Territory development

Darwin’s proposed Middle Arm Sustainable Development Precinct is set to be the heart of a new integrated infrastructure network in the Northern Territory, larger and better than what currently exists in northern Australia. However, the ...The StrategistBy Louise McCormick3 days ago

Darwin’s proposed Middle Arm Sustainable Development Precinct is set to be the heart of a new integrated infrastructure network in the Northern Territory, larger and better than what currently exists in northern Australia. However, the ...The StrategistBy Louise McCormick3 days ago - Grooming us for identity theft

No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago

- As tensions grow, an Australian AI safety institute is a no-brainer

Australia needs to deliver its commitment under the Seoul Declaration to create an Australian AI safety, or security, institute. Australia is the only signatory to the declaration that has yet to meet its commitments. Given ...The StrategistBy Greg Sadler3 days ago

Australia needs to deliver its commitment under the Seoul Declaration to create an Australian AI safety, or security, institute. Australia is the only signatory to the declaration that has yet to meet its commitments. Given ...The StrategistBy Greg Sadler3 days ago - Hine Ruhi (Slice Of Heaven)

Ko kōpū ka rere i te paeMe ko Hine RuhiTīaho mai tō arohaMe ko Hine RuhiDa da da ba du da da ba du da da da ba du da da da da da daDa da da ba du da da ba du da da da ba du da da ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago

Ko kōpū ka rere i te paeMe ko Hine RuhiTīaho mai tō arohaMe ko Hine RuhiDa da da ba du da da ba du da da da ba du da da da da da daDa da da ba du da da ba du da da da ba du da da ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago - ‘We can afford more drones, but not more homes’

Army, Navy and AirForce personnel in ceremonial dress: an ongoing staffing exodus means we may get more ships, drones and planes but not have enough ‘boots on the ground’ to use them. Photo: Lynn GrievesonLong stories short in Aotearoa’s political economy this morning: PM Christopher Luxon says the Government can ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

Army, Navy and AirForce personnel in ceremonial dress: an ongoing staffing exodus means we may get more ships, drones and planes but not have enough ‘boots on the ground’ to use them. Photo: Lynn GrievesonLong stories short in Aotearoa’s political economy this morning: PM Christopher Luxon says the Government can ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - Oliver’s struggle: a case study in the frustration of trying to join the ADF

If you’re a qualified individual looking to join the Australian Army, prepare for a world of frustration over the next 12 to 18 months. While thorough vetting is essential, the inefficiency of the Australian Defence ...The StrategistBy Kiana Lowry4 days ago

If you’re a qualified individual looking to join the Australian Army, prepare for a world of frustration over the next 12 to 18 months. While thorough vetting is essential, the inefficiency of the Australian Defence ...The StrategistBy Kiana Lowry4 days ago - NZD Freefall, Winston Peters Linked To Green Party Attack Ads & More

I’ve inserted a tidbit and rumours section1. Colonoscopy wait times increase, procedures drop under NationalWait times for urgent, non-urgent and surveillance colonoscopies all progressively worsened last year. Health NZ data shows the total number of publicly-funded colonoscopies dropped by more than 7 percent.Health NZ chief medical officer Helen Stokes-Lampard blamed ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī4 days ago

I’ve inserted a tidbit and rumours section1. Colonoscopy wait times increase, procedures drop under NationalWait times for urgent, non-urgent and surveillance colonoscopies all progressively worsened last year. Health NZ data shows the total number of publicly-funded colonoscopies dropped by more than 7 percent.Health NZ chief medical officer Helen Stokes-Lampard blamed ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī4 days ago - Tuesday 8 April

Three billion dollars has been wiped off the value of New Zealand’s share market as the rout of global financial markets caught up with the local market. A Sāmoan national has been sentenced for migrant exploitation and corruption following a five-year investigation that highlights the serious consequences of immigration fraud ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald4 days ago

Three billion dollars has been wiped off the value of New Zealand’s share market as the rout of global financial markets caught up with the local market. A Sāmoan national has been sentenced for migrant exploitation and corruption following a five-year investigation that highlights the serious consequences of immigration fraud ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald4 days ago - Wherefore now with Kiwirail

This is a guest post by Darren Davis. It originally appeared on his excellent blog, Adventures in Transitland, which we encourage you to check out. It is shared by kind permission. Rail Network Investment Plan quietly dropped While much media attention focused on the 31st March 2025 announcement that the replacement Cook ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post4 days ago

This is a guest post by Darren Davis. It originally appeared on his excellent blog, Adventures in Transitland, which we encourage you to check out. It is shared by kind permission. Rail Network Investment Plan quietly dropped While much media attention focused on the 31st March 2025 announcement that the replacement Cook ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post4 days ago - More unneeded officers, more military influence. Indonesia’s law revision is a mistake

Amendments to Indonesia’s military law risk undermining civilian supremacy and the country’s defence capabilities. Passed by the House of Representatives on 20 March, the main changes include raising the retirement age and allowing military officers ...The StrategistBy Alfin Febrian Basundoro and Jascha Ramba Santoso4 days ago

Amendments to Indonesia’s military law risk undermining civilian supremacy and the country’s defence capabilities. Passed by the House of Representatives on 20 March, the main changes include raising the retirement age and allowing military officers ...The StrategistBy Alfin Febrian Basundoro and Jascha Ramba Santoso4 days ago - Gordon Campbell On Peter Dutton’s Fading Election Prospects.

So New Zealand is about to spend $12 billion on our defence forces over the next four years – with $9 million of it being new money that is not being spent on pressing needs here at home. Somehow this lavish spend-up on Defence is “affordable,” says PM Christopher Luxon, ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor4 days ago

So New Zealand is about to spend $12 billion on our defence forces over the next four years – with $9 million of it being new money that is not being spent on pressing needs here at home. Somehow this lavish spend-up on Defence is “affordable,” says PM Christopher Luxon, ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor4 days ago - A letter to America from an appreciative ally

Donald Trump’s philosophy about the United States’ place in the world is historically selfish and will impoverish his country’s spirit. While he claimed last week to be ‘liberating’ Americans from the exploiters and freeloaders who’ve ...The StrategistBy David Wroe4 days ago

Donald Trump’s philosophy about the United States’ place in the world is historically selfish and will impoverish his country’s spirit. While he claimed last week to be ‘liberating’ Americans from the exploiters and freeloaders who’ve ...The StrategistBy David Wroe4 days ago - Myanmar’s scam centres demand ASEAN-Australia collaboration

China’s crackdown on cyber-scam centres on the Thailand-Myanmar border may cause a shift away from Mandarin, towards English-speaking victims. Scammers also used the 28 March earthquake to scam international victims. Australia, with its proven capabilities ...The StrategistBy Alice Wai and Fitriani4 days ago

China’s crackdown on cyber-scam centres on the Thailand-Myanmar border may cause a shift away from Mandarin, towards English-speaking victims. Scammers also used the 28 March earthquake to scam international victims. Australia, with its proven capabilities ...The StrategistBy Alice Wai and Fitriani4 days ago - The return of dirty politics

At the 2005 election campaign, the National Party colluded with a weirdo cult, the Exclusive Brethren, to run a secret hate campaign against the Greens. It was the first really big example of the rich using dark money to interfere in our democracy. And unfortunately, it seems that they're trying ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant4 days ago

At the 2005 election campaign, the National Party colluded with a weirdo cult, the Exclusive Brethren, to run a secret hate campaign against the Greens. It was the first really big example of the rich using dark money to interfere in our democracy. And unfortunately, it seems that they're trying ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant4 days ago - Our MOOC Denial101x has run its course

Many of you will know that in collaboration with the University of Queensland we created and ran the massive open online course (MOOC) "Denial101x - Making sense of climate science denial" on the edX platform. Within nine years - between April 2015 and February 2024 - we offered 15 runs ...4 days ago

Many of you will know that in collaboration with the University of Queensland we created and ran the massive open online course (MOOC) "Denial101x - Making sense of climate science denial" on the edX platform. Within nine years - between April 2015 and February 2024 - we offered 15 runs ...4 days ago - In trade, nothing can replace the US consumer. Still, Asian countries look to each other

How will the US assault on trade affect geopolitical relations within Asia? Will nations turn to China and seek protection by trading with each other? The happy snaps a week ago of the trade ministers ...The StrategistBy David Uren4 days ago

How will the US assault on trade affect geopolitical relations within Asia? Will nations turn to China and seek protection by trading with each other? The happy snaps a week ago of the trade ministers ...The StrategistBy David Uren4 days ago - Why Did Police Clear Brian Tamaki Of All Charges?

I mentioned this on Friday - but thought it deserved some emphasis.Auckland Waitematā District Commander Superintendent Naila Hassan has responded to Countering Hate Speech Aotearoa, saying police have cleared Brian Tamaki of all incitement charges relating to the Te Atatu library rainbow event assault.Hassan writes:..There is currently insufficient evidence to ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī4 days ago

I mentioned this on Friday - but thought it deserved some emphasis.Auckland Waitematā District Commander Superintendent Naila Hassan has responded to Countering Hate Speech Aotearoa, saying police have cleared Brian Tamaki of all incitement charges relating to the Te Atatu library rainbow event assault.Hassan writes:..There is currently insufficient evidence to ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī4 days ago - Reviewing the intelligence reviews (so far)

With the report of the recent intelligence review by Heather Smith and Richard Maude finally released, critics could look on and wonder: why all the fuss? After all, while the list of recommendations is substantial, ...The StrategistBy John Blaxland5 days ago

With the report of the recent intelligence review by Heather Smith and Richard Maude finally released, critics could look on and wonder: why all the fuss? After all, while the list of recommendations is substantial, ...The StrategistBy John Blaxland5 days ago - Healthy Beginnings, Hopeful Futures

Well, I don't know if I'm readyTo be the man I have to beI'll take a breath, I'll take her by my sideWe stand in awe, we've created lifeWith arms wide open under the sunlightWelcome to this place, I'll show you everythingSongwriters: Scott A. Stapp / Mark T. Tremonti.Today is ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago

Well, I don't know if I'm readyTo be the man I have to beI'll take a breath, I'll take her by my sideWe stand in awe, we've created lifeWith arms wide open under the sunlightWelcome to this place, I'll show you everythingSongwriters: Scott A. Stapp / Mark T. Tremonti.Today is ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago - Monday 7 April

Staff at Kāinga Ora are expecting details of another round of job cuts, with the Green Party claiming more than 500 jobs are set to go. The New Zealand Defence Force has made it easier for people to apply for a job in a bid to get more boots on ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald5 days ago

Staff at Kāinga Ora are expecting details of another round of job cuts, with the Green Party claiming more than 500 jobs are set to go. The New Zealand Defence Force has made it easier for people to apply for a job in a bid to get more boots on ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald5 days ago - Australia’s food security needs national-security frameworks

Australia’s agriculture sector and food system have prospered under a global rules-based system influenced by Western liberal values. But the assumptions, policy approaches and economic frameworks that have traditionally supported Australia’s food security are no ...The StrategistBy Andrew Henderson5 days ago

Australia’s agriculture sector and food system have prospered under a global rules-based system influenced by Western liberal values. But the assumptions, policy approaches and economic frameworks that have traditionally supported Australia’s food security are no ...The StrategistBy Andrew Henderson5 days ago - Trump just detonated a neutron bomb under the global economy, but NZ could win

Following Trump’s tariff announcement, US stock values fell by the most ever in value terms (US$6.6 trillion). Photo: Getty ImagesLong story shortest in Aotearoa’s political economy this morning: Donald Trump just detonated a neutron bomb under the globalised economy, but this time the Fed isn’t cutting interest rates to rescue ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

Following Trump’s tariff announcement, US stock values fell by the most ever in value terms (US$6.6 trillion). Photo: Getty ImagesLong story shortest in Aotearoa’s political economy this morning: Donald Trump just detonated a neutron bomb under the globalised economy, but this time the Fed isn’t cutting interest rates to rescue ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #14

A listing of 36 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, March 30, 2025 thru Sat, April 5, 2025. This week's roundup is again published by category and sorted by number of articles included in each. The formatting is a ...5 days ago

A listing of 36 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, March 30, 2025 thru Sat, April 5, 2025. This week's roundup is again published by category and sorted by number of articles included in each. The formatting is a ...5 days ago - Trump’s Secret Sauce Spills Over

This is a longer read.Summary:Trump’s tariffs are reckless, disastrous and hurt the poorest countries deeply. It will stoke inflation, and may cause another recession. Funds/investments around the world have tanked.Trump’s actions emulate the anti-economic logic of another right wing libertarian politician - Liz Truss. She had her political career cut ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī5 days ago

This is a longer read.Summary:Trump’s tariffs are reckless, disastrous and hurt the poorest countries deeply. It will stoke inflation, and may cause another recession. Funds/investments around the world have tanked.Trump’s actions emulate the anti-economic logic of another right wing libertarian politician - Liz Truss. She had her political career cut ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī5 days ago - Wouldn’t really go that far

We are all suckers for hope.He’s just being provocative, people will say, he wouldn’t really go that far. They wouldn’t really go that far.Germany in the 1920s and 30s was one of the world’s most educated, culturally sophisticated, and scientifically advanced societies.It had a strong democratic constitution with extensive civil ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack6 days ago

We are all suckers for hope.He’s just being provocative, people will say, he wouldn’t really go that far. They wouldn’t really go that far.Germany in the 1920s and 30s was one of the world’s most educated, culturally sophisticated, and scientifically advanced societies.It had a strong democratic constitution with extensive civil ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack6 days ago - Fact brief – Is Mars warming?

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Is Mars warming? Mars’ climate varies due to completely different reasons than Earth’s, and available data indicates no temperature trends comparable to Earth’s ...6 days ago

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Is Mars warming? Mars’ climate varies due to completely different reasons than Earth’s, and available data indicates no temperature trends comparable to Earth’s ...6 days ago - Maxing out – next steps for progressives

Max Harris and Max Rashbrooke discuss how we turn around the right wing slogans like nanny state, woke identity politics, and the inefficiency of the public sector – and how we build a progressive agenda. From Donald Trump to David Seymour, from Peter Dutton to Christopher Luxon, we are subject to a ...6 days ago

Max Harris and Max Rashbrooke discuss how we turn around the right wing slogans like nanny state, woke identity politics, and the inefficiency of the public sector – and how we build a progressive agenda. From Donald Trump to David Seymour, from Peter Dutton to Christopher Luxon, we are subject to a ...6 days ago - Maxing out – next steps for progressives

Max Harris and Max Rashbrooke discuss how we turn around the right wing slogans like nanny state, woke identity politics, and the inefficiency of the public sector – and how we build a progressive agenda. From Donald Trump to David Seymour, from Peter Dutton to Christopher Luxon, we are subject to a ...6 days ago

Max Harris and Max Rashbrooke discuss how we turn around the right wing slogans like nanny state, woke identity politics, and the inefficiency of the public sector – and how we build a progressive agenda. From Donald Trump to David Seymour, from Peter Dutton to Christopher Luxon, we are subject to a ...6 days ago

Related Posts

- Release: Students struggling as Govt sits on hands

The Government is continuing to sit on its hands as students struggle to pay rent due to delays with StudyLink. ...11 hours ago

The Government is continuing to sit on its hands as students struggle to pay rent due to delays with StudyLink. ...11 hours ago - Release: More must be done to stop children going hungry

More children are going hungry and statistics showing children in material hardship continue to get worse. ...13 hours ago

More children are going hungry and statistics showing children in material hardship continue to get worse. ...13 hours ago - Greens continue to call for Pacific Visa Waiver

The Green Party recognises the extension of visa allowances for our Pacific whānau as a step in the right direction but continues to call for a Pacific Visa Waiver. ...13 hours ago

The Green Party recognises the extension of visa allowances for our Pacific whānau as a step in the right direction but continues to call for a Pacific Visa Waiver. ...13 hours ago - More children going hungry under Coalition govt

The Government yesterday released its annual child poverty statistics, and by its own admission, more tamariki across Aotearoa are now living in material hardship. ...14 hours ago

The Government yesterday released its annual child poverty statistics, and by its own admission, more tamariki across Aotearoa are now living in material hardship. ...14 hours ago - Release: Longer wait for treatment under National

New Zealanders have waited longer to get an appointment with a specialist and to get elective surgery under the National Government. ...15 hours ago

New Zealanders have waited longer to get an appointment with a specialist and to get elective surgery under the National Government. ...15 hours ago - Ka mate te Pire- Ka ora te mana o Te Tiriti o Waitangi me te iwi Māori

Today, Te Pāti Māori join the motu in celebration as the Treaty Principles Bill is voted down at its second reading. “From the beginning, this Bill was never welcome in this House,” said Te Pāti Māori Co-Leader, Rawiri Waititi. “Our response to the first reading was one of protest: protesting ...1 day ago

Today, Te Pāti Māori join the motu in celebration as the Treaty Principles Bill is voted down at its second reading. “From the beginning, this Bill was never welcome in this House,” said Te Pāti Māori Co-Leader, Rawiri Waititi. “Our response to the first reading was one of protest: protesting ...1 day ago - Chris Hipkins speech: Treaty Principles Bill second reading

Normally, when I rise in this House to speak on a bill, I say it's a great privilege to speak on the bill. That is not the case today. ...1 day ago

Normally, when I rise in this House to speak on a bill, I say it's a great privilege to speak on the bill. That is not the case today. ...1 day ago - Release: End to the Treaty Principles Bill, but challenges remain ahead for Aotearoa

1 day ago

- Ka mate te Pire, ka ora Te Tiriti o Waitangi – Treaty Principles Bill dead, Te Tiriti o Waitangi m...

The Green Party is proud to have voted down the Coalition Government’s Treaty Principles Bill, an archaic piece of legislation that sought to attack the nation’s founding agreement. ...1 day ago

The Green Party is proud to have voted down the Coalition Government’s Treaty Principles Bill, an archaic piece of legislation that sought to attack the nation’s founding agreement. ...1 day ago - Member’s Bill an opportunity for climate action

A Member’s Bill in the name of Green Party MP Julie Anne Genter which aims to stop coal mining, the Crown Minerals (Prohibition of Mining) Amendment Bill, has been pulled from Parliament’s ‘biscuit tin’ today. ...1 day ago

A Member’s Bill in the name of Green Party MP Julie Anne Genter which aims to stop coal mining, the Crown Minerals (Prohibition of Mining) Amendment Bill, has been pulled from Parliament’s ‘biscuit tin’ today. ...1 day ago - Release: Bill to make trading laws fairer passes first hurdle

Labour MP Kieran McAnulty’s Members Bill to make the law simpler and fairer for businesses operating on Easter, Anzac and Christmas Days has passed its first reading after a conscience vote in Parliament. ...2 days ago

Labour MP Kieran McAnulty’s Members Bill to make the law simpler and fairer for businesses operating on Easter, Anzac and Christmas Days has passed its first reading after a conscience vote in Parliament. ...2 days ago - Release: Reserve Bank acts while Govt shrugs

Nicola Willis continues to sit on her hands amid a global economic crisis, leaving the Reserve Bank to act for New Zealanders who are worried about their jobs, mortgages, and KiwiSaver. ...2 days ago

Nicola Willis continues to sit on her hands amid a global economic crisis, leaving the Reserve Bank to act for New Zealanders who are worried about their jobs, mortgages, and KiwiSaver. ...2 days ago - Release: Property Law Amendment Bill pulled from ballot

A Bill to protect first home buyers and others from bad faith property vendors has been drawn from the Member’s Ballot. ...2 days ago

A Bill to protect first home buyers and others from bad faith property vendors has been drawn from the Member’s Ballot. ...2 days ago - Release: More children at risk of losing family connections

Karen Chhour is proposing to scrap Oranga Tamariki targets which aim to connect more children under state care with family and their culture. ...3 days ago

Karen Chhour is proposing to scrap Oranga Tamariki targets which aim to connect more children under state care with family and their culture. ...3 days ago - Release: David Parker made a difference – Hipkins

The Labour Leader today acknowledged and celebrated David Parker’s 23-year contribution to the Labour Party and to Parliament. ...3 days ago

The Labour Leader today acknowledged and celebrated David Parker’s 23-year contribution to the Labour Party and to Parliament. ...3 days ago - Release: David Parker to step down from Parliament

Long-serving Labour MP and former Minister David Parker has today announced his intention to leave Parliament. ...3 days ago

Long-serving Labour MP and former Minister David Parker has today announced his intention to leave Parliament. ...3 days ago - Release: Flaws in Govt’s climate strategy will cost us money

The Government’s plan to achieve our climate goals falls short, and will cost New Zealanders money and jobs. ...4 days ago

The Government’s plan to achieve our climate goals falls short, and will cost New Zealanders money and jobs. ...4 days ago - Green Party differing view on the Treaty Principles Bill

5 days ago

- Te Pāti Māori Urges Governor-General to Block Repeal of 7AA

Today, the Oranga Tamariki (Repeal of Section 7AA) Amendment Bill has passed its third and final reading, but there is one more stage before it becomes law. The Governor-General must give their ‘Royal assent’ for any bill to become legally enforceable. This means that, even if a bill gets voted ...1 week ago

Today, the Oranga Tamariki (Repeal of Section 7AA) Amendment Bill has passed its third and final reading, but there is one more stage before it becomes law. The Governor-General must give their ‘Royal assent’ for any bill to become legally enforceable. This means that, even if a bill gets voted ...1 week ago - Release: Abortion care quietly shelved amid staff shortage

Abortion care at Whakatāne Hospital has been quietly shelved, with patients told they will likely have to travel more than an hour to Tauranga to get the treatment they need. ...1 week ago

Abortion care at Whakatāne Hospital has been quietly shelved, with patients told they will likely have to travel more than an hour to Tauranga to get the treatment they need. ...1 week ago - Release: Govt guts Kāinga Ora, third of workforce under axe

The gutting of Kāinga Ora shows public housing is not a priority for this Government as it removes a third of the roles at the housing agency. ...1 week ago

The gutting of Kāinga Ora shows public housing is not a priority for this Government as it removes a third of the roles at the housing agency. ...1 week ago - Release: Thousands of submissions excluded from Treaty Principles Bill report

Thousands of New Zealanders’ submissions are missing from the official parliamentary record because the National-dominated Justice Select Committee has rushed work on the Treaty Principles Bill. ...1 week ago

Thousands of New Zealanders’ submissions are missing from the official parliamentary record because the National-dominated Justice Select Committee has rushed work on the Treaty Principles Bill. ...1 week ago - Release: Uncertainty remains over the impact of tariffs

Today’s announcement of 10 percent tariffs for New Zealand goods entering the United States is disappointing for exporters and consumers alike, with the long-lasting impact on prices and inflation still unknown. ...1 week ago

Today’s announcement of 10 percent tariffs for New Zealand goods entering the United States is disappointing for exporters and consumers alike, with the long-lasting impact on prices and inflation still unknown. ...1 week ago - Release: Worst February for building consents in over a decade

The National Government’s choices have contributed to a slow-down in the building sector, as thousands of people have lost their jobs in construction. ...1 week ago

The National Government’s choices have contributed to a slow-down in the building sector, as thousands of people have lost their jobs in construction. ...1 week ago - Release: Labour supports Willie Apiata’s selfless act

Willie Apiata’s decision to hand over his Victoria Cross to the Minister for Veterans is a powerful and selfless act, made on behalf of all those who have served our country. ...1 week ago

Willie Apiata’s decision to hand over his Victoria Cross to the Minister for Veterans is a powerful and selfless act, made on behalf of all those who have served our country. ...1 week ago - Te Pāti Māori MPs Denied Fundamental Rights in Privileges Committee Hearing

The Privileges Committee has denied fundamental rights to Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, Rawiri Waititi and Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke, breaching their own standing orders, breaching principles of natural justice, and highlighting systemic prejudice and discrimination within our parliamentary processes. The three MPs were summoned to the privileges committee following their performance of a haka ...1 week ago

The Privileges Committee has denied fundamental rights to Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, Rawiri Waititi and Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke, breaching their own standing orders, breaching principles of natural justice, and highlighting systemic prejudice and discrimination within our parliamentary processes. The three MPs were summoned to the privileges committee following their performance of a haka ...1 week ago - Release: Govt health and safety changes put workers at risk

Changes to New Zealand’s health and safety laws will strip back key protections for small businesses and put working Kiwis at greater risk. ...2 weeks ago

Changes to New Zealand’s health and safety laws will strip back key protections for small businesses and put working Kiwis at greater risk. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Kiwis worse off this April thanks to Govt choices

April 1 used to be a day when workers could count on a pay rise with stronger support for those doing it tough, but that’s not the case under this Government. ...2 weeks ago

April 1 used to be a day when workers could count on a pay rise with stronger support for those doing it tough, but that’s not the case under this Government. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Three more years for Interislander ferries

Winston Peters is shopping for smaller ferries after Nicola Willis torpedoed the original deal, which would have delivered new rail enabled ferries next year. ...2 weeks ago

Winston Peters is shopping for smaller ferries after Nicola Willis torpedoed the original deal, which would have delivered new rail enabled ferries next year. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Myanmar junta must stop the airstrikes

The Government should work with other countries to press the Myanmar military regime to stop its bombing campaign especially while the country recovers from the devastating earthquake. ...2 weeks ago

The Government should work with other countries to press the Myanmar military regime to stop its bombing campaign especially while the country recovers from the devastating earthquake. ...2 weeks ago - Release: National failing to deliver on supermarkets

National is paying lip service to its promises to bring down the cost of living, failing to make any meaningful change in the grocery sector. ...2 weeks ago

National is paying lip service to its promises to bring down the cost of living, failing to make any meaningful change in the grocery sector. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Labour backs farmers’ call for better process on GE

2 weeks ago

- Release: Bar still too high for small mental health providers

Small mental health providers will still be locked out of co-funding from the Mental Health Innovation Fund despite a lower threshold. ...2 weeks ago

Small mental health providers will still be locked out of co-funding from the Mental Health Innovation Fund despite a lower threshold. ...2 weeks ago - Greens call for Govt to scrap proposed ECE changes

The Green Party is calling for the Government to scrap proposed changes to Early Childhood Care, after attending a petition calling for the Government to ‘Put tamariki at the heart of decisions about ECE’. ...2 weeks ago

The Green Party is calling for the Government to scrap proposed changes to Early Childhood Care, after attending a petition calling for the Government to ‘Put tamariki at the heart of decisions about ECE’. ...2 weeks ago - NZ First Introduces Bill That Gives Democracy Back To The People

New Zealand First has introduced a Member’s Bill today that will remove the power of MPs conscience votes and ensure mandatory national referendums are held before any conscience issues are passed into law. “We are giving democracy and power back to the people”, says New Zealand First Leader Winston Peters. ...2 weeks ago

New Zealand First has introduced a Member’s Bill today that will remove the power of MPs conscience votes and ensure mandatory national referendums are held before any conscience issues are passed into law. “We are giving democracy and power back to the people”, says New Zealand First Leader Winston Peters. ...2 weeks ago - Speech: Navigating the New World (Dis)order in Turbulent Times

Welcome to members of the diplomatic corp, fellow members of parliament, the fourth estate, foreign affairs experts, trade tragics, ladies and gentlemen. ...2 weeks ago

Welcome to members of the diplomatic corp, fellow members of parliament, the fourth estate, foreign affairs experts, trade tragics, ladies and gentlemen. ...2 weeks ago - Te Pāti Māori Call for Mandatory Police Body Cameras

In recent weeks, disturbing instances of state-sanctioned violence against Māori have shed light on the systemic racism permeating our institutions. An 11-year-old autistic Māori child was forcibly medicated at the Henry Bennett Centre, a 15-year-old had his jaw broken by police in Napier, kaumātua Dean Wickliffe went on a hunger ...2 weeks ago

In recent weeks, disturbing instances of state-sanctioned violence against Māori have shed light on the systemic racism permeating our institutions. An 11-year-old autistic Māori child was forcibly medicated at the Henry Bennett Centre, a 15-year-old had his jaw broken by police in Napier, kaumātua Dean Wickliffe went on a hunger ...2 weeks ago - Release: Kiwis lose faith in job market

Confidence in the job market has continued to drop to its lowest level in five years as more New Zealanders feel uncertain about finding work, keeping their jobs, and getting decent pay, according to the latest Westpac-McDermott Miller Employment Confidence Index. ...2 weeks ago

Confidence in the job market has continued to drop to its lowest level in five years as more New Zealanders feel uncertain about finding work, keeping their jobs, and getting decent pay, according to the latest Westpac-McDermott Miller Employment Confidence Index. ...2 weeks ago - Greens question Govt commitment to environmental protection with RMA reform

The Greens are calling on the Government to follow through on their vague promises of environmental protection in their Resource Management Act (RMA) reform. ...3 weeks ago

The Greens are calling on the Government to follow through on their vague promises of environmental protection in their Resource Management Act (RMA) reform. ...3 weeks ago - Release: Govt must tackle meth use crisis

New data shows methamphetamine use is spiralling out of control while the Government sits on its hands. ...3 weeks ago

New data shows methamphetamine use is spiralling out of control while the Government sits on its hands. ...3 weeks ago

Related Posts

- New planning laws to end the culture of ‘no’

The Government’s new planning legislation to replace the Resource Management Act will make it easier to get things done while protecting the environment, say Minister Responsible for RMA Reform Chris Bishop and Under-Secretary Simon Court. “The RMA is broken and everyone knows it. It makes it too hard to build ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz3 weeks ago

The Government’s new planning legislation to replace the Resource Management Act will make it easier to get things done while protecting the environment, say Minister Responsible for RMA Reform Chris Bishop and Under-Secretary Simon Court. “The RMA is broken and everyone knows it. It makes it too hard to build ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz3 weeks ago - New Zealand & India Comprehensive FTA consultation begins

Trade and Investment Minister Todd McClay has today launched a public consultation on New Zealand and India’s negotiations of a formal comprehensive Free Trade Agreement. “Negotiations are getting underway, and the Public’s views will better inform us in the early parts of this important negotiation,” Mr McClay says. We are ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz3 weeks ago

Trade and Investment Minister Todd McClay has today launched a public consultation on New Zealand and India’s negotiations of a formal comprehensive Free Trade Agreement. “Negotiations are getting underway, and the Public’s views will better inform us in the early parts of this important negotiation,” Mr McClay says. We are ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz3 weeks ago - Cost of living support coming for 1.5 million New Zealanders

More than 900 thousand superannuitants and almost five thousand veterans are among the New Zealanders set to receive a significant financial boost from next week, an uplift Social Development and Employment Minister Louise Upston says will help support them through cost-of-living challenges. “I am pleased to confirm that from 1 ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz3 weeks ago

More than 900 thousand superannuitants and almost five thousand veterans are among the New Zealanders set to receive a significant financial boost from next week, an uplift Social Development and Employment Minister Louise Upston says will help support them through cost-of-living challenges. “I am pleased to confirm that from 1 ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz3 weeks ago

Related Posts

- Election Diary: Labor breaks practice of preferencing Greens to protect Jewish MP Josh Burns

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra It takes a bit for Labor not to preference the Greens but on Friday it was announced that in the Melbourne seat of Macnamara, where Jewish MP Josh Burns is embattled, the ALP will run ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation4 hours ago

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra It takes a bit for Labor not to preference the Greens but on Friday it was announced that in the Melbourne seat of Macnamara, where Jewish MP Josh Burns is embattled, the ALP will run ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation4 hours ago - ‘Delusional’ Treaty Principles Bill scrapped but fight for Te Tiriti just beginning, say lawyers...

By Layla Bailey-McDowell, RNZ Māori news journalist Legal experts and Māori advocates say the fight to protect Te Tiriti is only just beginning — as the controversial Treaty Principles Bill is officially killed in Parliament. The bill — which seeks to redefine the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi — ...Evening ReportBy Asia Pacific Report5 hours ago

By Layla Bailey-McDowell, RNZ Māori news journalist Legal experts and Māori advocates say the fight to protect Te Tiriti is only just beginning — as the controversial Treaty Principles Bill is officially killed in Parliament. The bill — which seeks to redefine the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi — ...Evening ReportBy Asia Pacific Report5 hours ago - Coalition plan to dump fuel efficiency penalties would make Australia a global outlier

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Anna Mortimore, Lecturer, Griffith Business School, Griffith University The Coalition has announced it would, if elected to government, weaken a scheme aimed at cutting car emissions. The scheme, known as the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard (NVES), was introduced by the Albanese government ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation6 hours ago

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Anna Mortimore, Lecturer, Griffith Business School, Griffith University The Coalition has announced it would, if elected to government, weaken a scheme aimed at cutting car emissions. The scheme, known as the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard (NVES), was introduced by the Albanese government ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation6 hours ago - Peter Dutton’s climate policy backslide threatens Australia’s clout in the Pacific – right whe...

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Wesley Morgan, Research Associate, Institute for Climate Risk and Response, UNSW Sydney Australia’s relationship with its regional neighbours could be in doubt under a Coalition government after two Pacific leaders challenged Opposition Leader Peter Dutton over his weak climate stance. This week, ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation6 hours ago