The politics of high inflation – can governments do anything?

The politics of high inflation – can governments do anything?

Written By:

nickkelly - Date published:

10:46 am, May 19th, 2022 - 13 comments

Categories: economy, Europe, Financial markets, Free Trade, Globalisation, inequality, International, Media, Politics, uk politics, Ukraine, us politics -

Tags: cost of living, inflation, Joe Biden, nick kelly, NZ Labour, scott morrison, UK Conservatives, World Economic Forum

Britons woke up to the news today that inflation in the UK has hit a 40 year high of 9%. Recent increases to power bills, fuel and groceries have in no small part driven this inflationary pressure and indications are that prices could increase further. The bank of England governor has called for wage restraint fearing that this could drive inflation even higher, though with the cost of living rising so quickly this call will likely fall on deaf ears.The recent losses in local body elections and lacklustre polling for Boris Johnson’s Conservatives is in part due to the rising cost of living. But is this all just a case of bad economic management by the Conservatives?

My usual reference point is comparing and contrasting the UK and New Zealand situations, having lived in both countries. New Zealand’s inflation rate is at a 30-year high hitting 6.9%. A friend in NZ recently asked if I could send petrol over from the UK as the cost had gone up too much over there, the joke soon fell flat when I told them how much a tank of petrol cost here in the UK. In New Zealand, the opposition has been quick to blame the Labour Government in New Zealand for this, at a time when support for the government is falling fast. Having won a record majority in 2020 for their handling of the pandemic, Jacinda’s government now faces a backlash over coronavirus restrictions and is taking the blame for current economic challenges. Commentary in the New Zealand media also tends to focus on inflation as a domestic issue, as such much of the commentary is often wide of the mark.

In Australia, the country goes to the polls for their first federal election since the pandemic. Whilst polling numbers are still fairly close there is a real possibility the right of centre Liberal Coalition Government led by Scott Morrison may lose, in no small part due to inflation and the rising cost of living. Whilst there are plenty of good reasons to vote out the Coalition government, not the least their inaction on climate change, like in Britain and New Zealand, is the cost of living increase in Australia really down to the federal government?

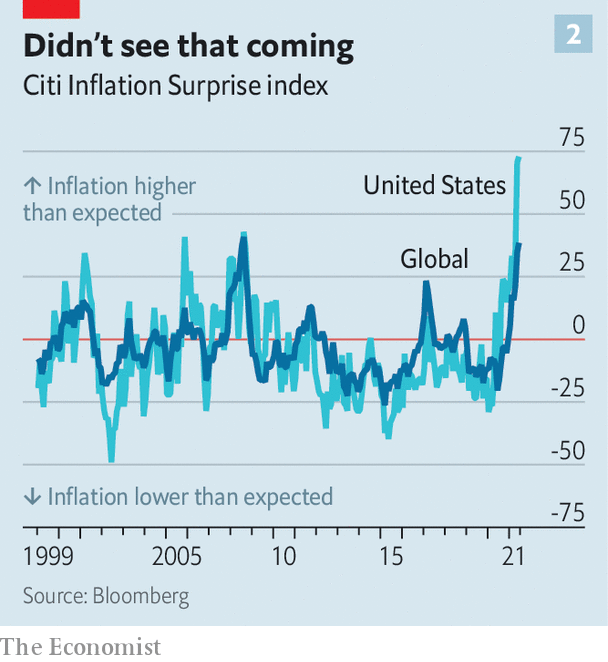

In the US, President Biden and the Democrat-controlled House and Senate are facing an uphill battle in the November midterms against a Republican Party now very much aligned to Trumpian politics. For the Biden administration there appear to be few options to control inflation in the short term. I have previously blogged about the limitations of the US political system and it is no surprise that many Americans yet again feel frustrated. However, it is clear that this is not a crisis limited to any single nation-state, what we are dealing with is a global inflation problem.

At the start of the pandemic, I wrote a blog post outlining how there would be long lasting economic ramifications of this crisis. This, along with the Russian invasion of Ukraine is driving inflation and causing economic uncertainty. This is particularly challenging for much of Europe where there is a high level of reliance on Russian Oil and Gas and moves to end this reliance will see short term price hikes and energy shortages.

Previously, I have written about the importance of global governance and how our current global governance institutions are not up to the challenges we face in the 21st century. The current crisis illustrates this more than ever. At the current time, we turn to the nation-state and in democratic countries we as voters can hold our leaders to account for what happens, including economic management. In reality, how much can Jacinda Ardern, Boris Johnson, Scott Morrison, Ursula von der Leyen or Joe Biden or any other world leader do? When finance Ministers do the national budget each year, many of the key economic factors are determined by external factors, not by their government’s decisions. Likewise, we can beat up the Bank of England, the Reserve Bank in New Zealand or other central banks for not controlling inflation within the targets they have been set, but they did not cause a global pandemic, invade Ukraine or control many of the key drivers of international inflation at that time.

This is not to let governments off the hook, as they still have the power to mitigate the effect of high inflation. Governments have the power to reduce or remove sales taxes, regulate pricing or support people on low incomes through benefits or policies that help lift wages. On the global stage, finance ministers when they attend the yearly Davos meeting, or leaders who attend the G20 meetings, need to be doing more to develop a global economic strategy that can protect against these sorts of shocks. Further, they need to create global governance institutions that can ensure a stable global economy that delivers for everyone, not just now but into the future. This is what we should be demanding of our governments.

Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s the big push was for globalisation, which in reality was a push for removing tariffs and international market liberalisation. The anti-globalisation movement of the time often took the position that this agenda weakened the nation-state and undermined democracy. The problem, which neither side really understood, is that in a world where we for a long time have depended on international trade but also on the movement of people, relying on national governments to resolve this will inevitably fail. Margaret Thatcher, in the introduction to her memoir The Downing Street Years, claimed the following:

An internationalism which seeks to supersede the nation-state, however, will founder quickly upon the reality that very few people are prepared to make genuine sacrifices for it

Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street years, page 11

Yes, in terms of consciousness people still hold nationalism and their own country in high regard. But where we increasingly see countries with governments of all different colours struggling to control the cost of living, at some point we must face the fact that an international response is required. People may not believe in current global governance institutions or be “prepared to make genuine sacrifices” for them. But they may do if these institutions were in fact giving people a better quality of life by controlling inflation and the cost of living. At the time of writing, this all seems somewhat academic, with there being little likelihood of an international response, other than some short term cooperation to control the immediate crisis without looking at the underlying long term problems. Yet it is clear that we will continue to face these economic challenges with tools that are ill-equipped to face the problems. Only a truly international response can create an economy that delivers for all.

Related Posts

13 comments on “The politics of high inflation – can governments do anything? ”

- Comments are now closed

- Comments are now closed

Recent Comments

- weka to Drowsy M. Kram on

- weka to Belladonna on

- Belladonna to weka on

- weka to Belladonna on

- dpalenski on

- feijoa to Tiger Mountain on

- AB to Belladonna on

- Belladonna to Stephen D on

- Stephen D on

- alwyn to Belladonna on

- Belladonna to AB on

- weka to Tiger Mountain on

- weka to Belladonna on

- weka to Hunter Thompson II on

- Tiger Mountain to Jimmy on

- Belladonna to Jimmy on

- Belladonna to Hunter Thompson II on

- Jimmy on

- Belladonna on

- Belladonna to Ad on

- tc to Patricia Bremner on

- Kay to Patricia Bremner on

- Kay on

- Res Publica to Anne on

- Shanreagh to Res Publica on

- weka to Psycho Milt on

- Psycho Milt to weka on

- weka to Bearded Git on

- weka to Bearded Git on

- gsays to Bearded Git on

- Bearded Git to Res Publica on

- Bearded Git to gsays on

- Bearded Git to weka on

- gsays to Bearded Git on

- weka to Bearded Git on

- weka to Bearded Git on

- Bearded Git to weka on

- Bearded Git to gsays on

- Bearded Git to weka on

- Bearded Git to Ad on

- Descendant Of Smith to weka on

- gsays to Bearded Git on

- Barfly on

Recent Posts

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Incognito

-

by lprent

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by Incognito

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by advantage

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

-

by lprent

-

by weka

-

by advantage

-

by Guest post

-

by Incognito

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Guest post

-

by Guest post

-

by advantage

-

by mickysavage

- What does India Want? What is New Zealand willing to give?

2 hours ago

- President Trump is redefining America’s international role, and Australia has influence

In the week of Australia’s 3 May election, ASPI will release Agenda for Change 2025: preparedness and resilience in an uncertain world, a report promoting public debate and understanding on issues of strategic importance to ...The StrategistBy Nerida King3 hours ago

In the week of Australia’s 3 May election, ASPI will release Agenda for Change 2025: preparedness and resilience in an uncertain world, a report promoting public debate and understanding on issues of strategic importance to ...The StrategistBy Nerida King3 hours ago - Simeon Brown Gaslights Doctors

Yesterday, 5,500 senior doctors across Aotearoa New Zealand voted overwhelmingly to strike for a day.This is the first time in New Zealand ASMS members have taken strike action for 24 hours.They are asking the government to fund them and account for resource shortfalls.Vacancies are critical - 45-50% in some regions.The ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī3 hours ago

Yesterday, 5,500 senior doctors across Aotearoa New Zealand voted overwhelmingly to strike for a day.This is the first time in New Zealand ASMS members have taken strike action for 24 hours.They are asking the government to fund them and account for resource shortfalls.Vacancies are critical - 45-50% in some regions.The ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī3 hours ago - ACT’s “Tough on Crime” Facade Crumbles with Jago’s Appeal

4 hours ago

- Judith Collins’ Hypocrisy: War Drums Over Welfare

Judith Collins is a seasoned master at political hypocrisy. As New Zealand’s Defence Minister, she's recently been banging the war drum, announcing a jaw-dropping $12 billion boost to the defence budget over the next four years, all while the coalition of chaos cries poor over housing, health, and education.Apparently, there’s ...5 hours ago

Judith Collins is a seasoned master at political hypocrisy. As New Zealand’s Defence Minister, she's recently been banging the war drum, announcing a jaw-dropping $12 billion boost to the defence budget over the next four years, all while the coalition of chaos cries poor over housing, health, and education.Apparently, there’s ...5 hours ago - Making the most of it

I’m on the London Overground watching what the phones people are holding are doing to their faces: The man-bun guy who could not be less impressed by what he's seeing but cannot stop reading; the woman who's impatient for a response; the one who’s frowning; the one who’s puzzled; the ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack5 hours ago

I’m on the London Overground watching what the phones people are holding are doing to their faces: The man-bun guy who could not be less impressed by what he's seeing but cannot stop reading; the woman who's impatient for a response; the one who’s frowning; the one who’s puzzled; the ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack5 hours ago - Maranga Ake

You don't have no prescriptionYou don't have to take no pillsYou don't have no prescriptionAnd baby don't have to take no pillsIf you come to see meDoctor Brown will cure your ills.Songwriters: Waymon Glasco.Dr Luxon. Image: David and Grok.First, they came for the Bottom FeedersAnd I did not speak outBecause ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel6 hours ago

You don't have no prescriptionYou don't have to take no pillsYou don't have no prescriptionAnd baby don't have to take no pillsIf you come to see meDoctor Brown will cure your ills.Songwriters: Waymon Glasco.Dr Luxon. Image: David and Grok.First, they came for the Bottom FeedersAnd I did not speak outBecause ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel6 hours ago - Bernard’s Dawn Chorus & Pick ‘n’ Mix for Wednesday, April 16

The Health Minister says the striking doctors already “well remunerated,” and are “walking away from” and “hurting” their patients. File photo: Lynn GrievesonLong stories short from our political economy on Wednesday, April 16:Simeon Brown has attacked1 doctors striking for more than a 1.5% pay rise as already “well remunerated,” even ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 hours ago

The Health Minister says the striking doctors already “well remunerated,” and are “walking away from” and “hurting” their patients. File photo: Lynn GrievesonLong stories short from our political economy on Wednesday, April 16:Simeon Brown has attacked1 doctors striking for more than a 1.5% pay rise as already “well remunerated,” even ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 hours ago - Strengthening Australia’s space cooperation with South Korea

The time is ripe for Australia and South Korea to strengthen cooperation in space, through embarking on joint projects and initiatives that offer practical outcomes for both countries. This is the finding of a new ...The StrategistBy Malcolm Davis6 hours ago

The time is ripe for Australia and South Korea to strengthen cooperation in space, through embarking on joint projects and initiatives that offer practical outcomes for both countries. This is the finding of a new ...The StrategistBy Malcolm Davis6 hours ago - They Can Only Talk About One Thing

Hi,When Trump raised tariffs against China to 145%, he destined many small businesses to annihilation. The Daily podcast captured the mass chaos by zooming in and talking to one person, Beth Benike, a small-business owner who will likely lose her home very soon.She pointed out that no, she wasn’t surprised ...David FarrierBy David Farrier8 hours ago

Hi,When Trump raised tariffs against China to 145%, he destined many small businesses to annihilation. The Daily podcast captured the mass chaos by zooming in and talking to one person, Beth Benike, a small-business owner who will likely lose her home very soon.She pointed out that no, she wasn’t surprised ...David FarrierBy David Farrier8 hours ago - National’s Inflation Shame: Kiwis Pay the Price

National’s handling of inflation and the cost-of-living crisis is an utter shambles and a gutless betrayal of every Kiwi scraping by. The Coalition of Chaos Ministers strut around preaching about how effective their policies are, but really all they're doing is perpetuating a cruel and sick joke of undelivered promises, ...8 hours ago

National’s handling of inflation and the cost-of-living crisis is an utter shambles and a gutless betrayal of every Kiwi scraping by. The Coalition of Chaos Ministers strut around preaching about how effective their policies are, but really all they're doing is perpetuating a cruel and sick joke of undelivered promises, ...8 hours ago - Winston’s Mate Rhys Williams Has Been Unmasked

Most people wouldn't have heard of a little worm like Rhys Williams, a so-called businessman and former NZ First member, who has recently been unmasked as the venomous troll behind a relentless online campaign targeting Green Party MP Benjamin Doyle.According to reports, Williams has been slinging mud at Doyle under ...19 hours ago

Most people wouldn't have heard of a little worm like Rhys Williams, a so-called businessman and former NZ First member, who has recently been unmasked as the venomous troll behind a relentless online campaign targeting Green Party MP Benjamin Doyle.According to reports, Williams has been slinging mud at Doyle under ...19 hours ago - Idiocy, Opportunity

Illustration credit: Jonathan McHugh (New Statesman)The other day, a subscriber said they were unsubscribing because they needed “some good news”.I empathised. Don’t we all.I skimmed a NZME article about the impacts of tariffs this morning with analysis from Kiwibank’s Jarrod Kerr. Kerr, their Chief Economist, suggested another recession is the ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī20 hours ago

Illustration credit: Jonathan McHugh (New Statesman)The other day, a subscriber said they were unsubscribing because they needed “some good news”.I empathised. Don’t we all.I skimmed a NZME article about the impacts of tariffs this morning with analysis from Kiwibank’s Jarrod Kerr. Kerr, their Chief Economist, suggested another recession is the ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī20 hours ago - US allies must band together in weapons development

Let’s assume, as prudence demands we assume, that the United States will not at any predictable time go back to being its old, reliable self. This means its allies must be prepared indefinitely to lean ...The StrategistBy Bill Sweetman21 hours ago

Let’s assume, as prudence demands we assume, that the United States will not at any predictable time go back to being its old, reliable self. This means its allies must be prepared indefinitely to lean ...The StrategistBy Bill Sweetman21 hours ago - I’ve been reading

Over the last three rather tumultuous US trade policy weeks, I’ve read these four books. I started with Irwin (whose book had sat on my pile for years, consulted from time to time but not read) in a week of lots of flights and hanging around airports/hotels, and then one ...Croaking CassandraBy Michael Reddell21 hours ago

Over the last three rather tumultuous US trade policy weeks, I’ve read these four books. I started with Irwin (whose book had sat on my pile for years, consulted from time to time but not read) in a week of lots of flights and hanging around airports/hotels, and then one ...Croaking CassandraBy Michael Reddell21 hours ago - This is not the time for increasing Indonesia’s defence spending

Indonesia could do without an increase in military spending that the Ministry of Defence is proposing. The country has more pressing issues, including public welfare and human rights. Moreover, the transparency and accountability to justify ...The StrategistBy Yokie Rahmad Isjchwansyah22 hours ago

Indonesia could do without an increase in military spending that the Ministry of Defence is proposing. The country has more pressing issues, including public welfare and human rights. Moreover, the transparency and accountability to justify ...The StrategistBy Yokie Rahmad Isjchwansyah22 hours ago - FSU Supports Chris Milne’s Right to Make Death Threats

22 hours ago

- Winston is inciting terrorism

That's the conclusion of a report into security risks against Green MP Benjamin Doyle, in the wake of Winston Peters' waging a homophobic hate-campaign against them: GRC’s report said a “hostility network” of politicians, commentators, conspiracy theorists, alternative media outlets and those opposed to the rainbow community had produced ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant23 hours ago

That's the conclusion of a report into security risks against Green MP Benjamin Doyle, in the wake of Winston Peters' waging a homophobic hate-campaign against them: GRC’s report said a “hostility network” of politicians, commentators, conspiracy theorists, alternative media outlets and those opposed to the rainbow community had produced ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant23 hours ago - Winston is inciting terrorism

That's the conclusion of a report into security risks against Green MP Benjamin Doyle, in the wake of Winston Peters' waging a homophobic hate-campaign against them: GRC’s report said a “hostility network” of politicians, commentators, conspiracy theorists, alternative media outlets and those opposed to the rainbow community had produced ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant23 hours ago

That's the conclusion of a report into security risks against Green MP Benjamin Doyle, in the wake of Winston Peters' waging a homophobic hate-campaign against them: GRC’s report said a “hostility network” of politicians, commentators, conspiracy theorists, alternative media outlets and those opposed to the rainbow community had produced ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant23 hours ago - Why has Hamish Campbell Gone Into Hiding?

National Party MP Hamish Campbell’s ties to the secretive Two By Twos "church" raises serious questions that are not being answered. This shadowy group, currently being investigated by the FBI for numerous cases of child abuse, hides behind a facade of faith while Campbell dodges scrutiny, claiming it’s a “private ...24 hours ago

National Party MP Hamish Campbell’s ties to the secretive Two By Twos "church" raises serious questions that are not being answered. This shadowy group, currently being investigated by the FBI for numerous cases of child abuse, hides behind a facade of faith while Campbell dodges scrutiny, claiming it’s a “private ...24 hours ago - Why has Hamish Campbell Gone Into Hiding?

National Party MP Hamish Campbell’s ties to the secretive Two By Twos "church" raises serious questions that are not being answered. This shadowy group, currently being investigated by the FBI for numerous cases of child abuse, hides behind a facade of faith while Campbell dodges scrutiny, claiming it’s a “private ...24 hours ago

National Party MP Hamish Campbell’s ties to the secretive Two By Twos "church" raises serious questions that are not being answered. This shadowy group, currently being investigated by the FBI for numerous cases of child abuse, hides behind a facade of faith while Campbell dodges scrutiny, claiming it’s a “private ...24 hours ago - The Government is cutting, just as the economic recovery is stalling

The economy is not doing what it was supposed to when PM Christopher Luxon said in January it was ‘going for growth.’ Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāLong stories short from our political economy on Tuesday, April 15:New Zealand’s economic recovery is stalling, according to business surveys, retail spending and ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago

The economy is not doing what it was supposed to when PM Christopher Luxon said in January it was ‘going for growth.’ Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāLong stories short from our political economy on Tuesday, April 15:New Zealand’s economic recovery is stalling, according to business surveys, retail spending and ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago - For a safer Symonds Street

This is a guest post by Lewis Creed, managing editor of the University of Auckland student publication Craccum, which is currently running a campaign for a safer Symonds Street in the wake of a horrific recent crash. The post has two parts: 1) Craccum’s original call for safety (6 ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post1 day ago

This is a guest post by Lewis Creed, managing editor of the University of Auckland student publication Craccum, which is currently running a campaign for a safer Symonds Street in the wake of a horrific recent crash. The post has two parts: 1) Craccum’s original call for safety (6 ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post1 day ago - Tuesday 15 April

NZCTU President Richard Wagstaff has published an opinion piece which makes the case for a different approach to economic development, as proposed in the CTU’s Aotearoa Reimagined programme. The number of people studying to become teachers has jumped after several years of low enrolment. The coalition has directed Health New ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald1 day ago

NZCTU President Richard Wagstaff has published an opinion piece which makes the case for a different approach to economic development, as proposed in the CTU’s Aotearoa Reimagined programme. The number of people studying to become teachers has jumped after several years of low enrolment. The coalition has directed Health New ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald1 day ago - As China’s AI industry grows, Australia must support its own

The growth of China’s AI industry gives it great influence over emerging technologies. That creates security risks for countries using those technologies. So, Australia must foster its own domestic AI industry to protect its interests. ...The StrategistBy Hassan Gad1 day ago

The growth of China’s AI industry gives it great influence over emerging technologies. That creates security risks for countries using those technologies. So, Australia must foster its own domestic AI industry to protect its interests. ...The StrategistBy Hassan Gad1 day ago - Luxon’s Economic Mismanagement

Unfortunately we have another National Party government in power at the moment, and as a consequence, another economic dumpster fire taking hold. Inflation’s hurting Kiwis, and instead of providing relief, National is fiddling while wallets burn.Prime Minister Chris Luxon's response is a tired remix of tax cuts for the rich ...1 day ago

Unfortunately we have another National Party government in power at the moment, and as a consequence, another economic dumpster fire taking hold. Inflation’s hurting Kiwis, and instead of providing relief, National is fiddling while wallets burn.Prime Minister Chris Luxon's response is a tired remix of tax cuts for the rich ...1 day ago - Girls and Boys

Girls who are boys who like boys to be girlsWho do boys like they're girls, who do girls like they're boysAlways should be someone you really loveSongwriters: Damon Albarn / Graham Leslie Coxon / Alexander Rowntree David / Alexander James Steven.Last month, I wrote about the Birds and Bees being ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 day ago

Girls who are boys who like boys to be girlsWho do boys like they're girls, who do girls like they're boysAlways should be someone you really loveSongwriters: Damon Albarn / Graham Leslie Coxon / Alexander Rowntree David / Alexander James Steven.Last month, I wrote about the Birds and Bees being ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 day ago - Australia can learn from Britain on cyber governance

Australia needs to reevaluate its security priorities and establish a more dynamic regulatory framework for cybersecurity. To advance in this area, it can learn from Britain’s Cyber Security and Resilience Bill, which presents a compelling ...The StrategistBy Andrew Horton and George Hlaing1 day ago

Australia needs to reevaluate its security priorities and establish a more dynamic regulatory framework for cybersecurity. To advance in this area, it can learn from Britain’s Cyber Security and Resilience Bill, which presents a compelling ...The StrategistBy Andrew Horton and George Hlaing1 day ago - Gordon Campbell On Why The US Stands To Lose The Tariff Wars

Deputy PM Winston Peters likes nothing more than to portray himself as the only wise old head while everyone else is losing theirs. Yet this time, his “old master” routine isn’t working. What global trade is experiencing is more than the usual swings and roundabouts of market sentiment. President Donald ...Gordon CampbellBy ScoopEditor2 days ago

Deputy PM Winston Peters likes nothing more than to portray himself as the only wise old head while everyone else is losing theirs. Yet this time, his “old master” routine isn’t working. What global trade is experiencing is more than the usual swings and roundabouts of market sentiment. President Donald ...Gordon CampbellBy ScoopEditor2 days ago - Why is there no progress in Ukrainian war peace talks?

President Trump’s hopes of ending the war in Ukraine seemed more driven by ego than realistic analysis. Professor Vladimir Brovkin’s latest video above highlights the internal conflicts within the USA, Russia, Europe, and Ukraine, which are currently hindering peace talks and clarity. Brovkin pointed out major contradictions within ...Open ParachuteBy Ken2 days ago

President Trump’s hopes of ending the war in Ukraine seemed more driven by ego than realistic analysis. Professor Vladimir Brovkin’s latest video above highlights the internal conflicts within the USA, Russia, Europe, and Ukraine, which are currently hindering peace talks and clarity. Brovkin pointed out major contradictions within ...Open ParachuteBy Ken2 days ago - Ani O’Brien has Zero Credibility

In the cesspool that is often New Zealand’s online political discourse, few figures wield their influence as destructively as Ani O’Brien. Masquerading as a champion of free speech and women’s rights, O’Brien’s campaigns are a masterclass in bad faith, built on a foundation of lies, selective outrage, and a knack ...2 days ago

In the cesspool that is often New Zealand’s online political discourse, few figures wield their influence as destructively as Ani O’Brien. Masquerading as a champion of free speech and women’s rights, O’Brien’s campaigns are a masterclass in bad faith, built on a foundation of lies, selective outrage, and a knack ...2 days ago - Australian policy does need more Asia—more Southeast Asia

The international challenge confronting Australia today is unparalleled, at least since the 1940s. It requires what the late Brendan Sargeant, a defence analyst, called strategic imagination. We need more than shrewd economic manoeuvring and a ...The StrategistBy Anthony Milner2 days ago

The international challenge confronting Australia today is unparalleled, at least since the 1940s. It requires what the late Brendan Sargeant, a defence analyst, called strategic imagination. We need more than shrewd economic manoeuvring and a ...The StrategistBy Anthony Milner2 days ago - EGU2025 – Picking and chosing sessions to attend on site in Vienna

This year's General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) will take place as a fully hybrid conference in both Vienna and online from April 27 to May 2. This year, I'll join the event on site in Vienna for the full week and I've already picked several sessions I plan ...2 days ago

This year's General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) will take place as a fully hybrid conference in both Vienna and online from April 27 to May 2. This year, I'll join the event on site in Vienna for the full week and I've already picked several sessions I plan ...2 days ago - Bookshelf: How China sees things

Here’s a book that looks not in at China but out from China. David Daokui Li’s China’s World View: Demystifying China to Prevent Global Conflict is a refreshing offering in that Li is very much ...The StrategistBy John West2 days ago

Here’s a book that looks not in at China but out from China. David Daokui Li’s China’s World View: Demystifying China to Prevent Global Conflict is a refreshing offering in that Li is very much ...The StrategistBy John West2 days ago - The Mirage of Chris Luxon’s Pre-Election Promises

The New Zealand National Party has long mastered the art of crafting messaging that resonates with a large number of desperate, often white middle-class, voters. From their 2023 campaign mantra of “getting our country back on track” to promises of economic revival, safer streets, and better education, their rhetoric paints ...2 days ago

The New Zealand National Party has long mastered the art of crafting messaging that resonates with a large number of desperate, often white middle-class, voters. From their 2023 campaign mantra of “getting our country back on track” to promises of economic revival, safer streets, and better education, their rhetoric paints ...2 days ago - To counter anti-democratic propaganda, step up funding for ABC International

A global contest of ideas is underway, and democracy as an ideal is at stake. Democracies must respond by lifting support for public service media with an international footprint. With the recent decision by the ...The StrategistBy Claire Gorman2 days ago

A global contest of ideas is underway, and democracy as an ideal is at stake. Democracies must respond by lifting support for public service media with an international footprint. With the recent decision by the ...The StrategistBy Claire Gorman2 days ago - What was the story re Orr’s resignation?

It is almost six weeks since the shock announcement early on the afternoon of Wednesday 5 March that the Governor of the Reserve Bank, Adrian Orr, was resigning effective 31 March, and that in fact he had already left and an acting Governor was already in place. Orr had been ...Croaking CassandraBy Michael Reddell2 days ago

It is almost six weeks since the shock announcement early on the afternoon of Wednesday 5 March that the Governor of the Reserve Bank, Adrian Orr, was resigning effective 31 March, and that in fact he had already left and an acting Governor was already in place. Orr had been ...Croaking CassandraBy Michael Reddell2 days ago - Monday 14 April

The PSA surveyed more than 900 of its members, with 55 percent of respondents saying AI is used at their place of work, despite most workers not being in trained in how to use the technology safely. Figures to be released on Thursday are expected to show inflation has risen ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago

The PSA surveyed more than 900 of its members, with 55 percent of respondents saying AI is used at their place of work, despite most workers not being in trained in how to use the technology safely. Figures to be released on Thursday are expected to show inflation has risen ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago - How to spot AI influence in Australia’s election campaign

Be on guard for AI-powered messaging and disinformation in the campaign for Australia’s 3 May election. And be aware that parties can use AI to sharpen their campaigning, zeroing in on issues that the technology ...The StrategistBy Niusha Shafiabady2 days ago

Be on guard for AI-powered messaging and disinformation in the campaign for Australia’s 3 May election. And be aware that parties can use AI to sharpen their campaigning, zeroing in on issues that the technology ...The StrategistBy Niusha Shafiabady2 days ago - David Seymour – Arsehole of the Week

Strap yourselves in, folks, it’s time for another round of Arsehole of the Week, and this week’s golden derrière trophy goes to—drumroll, please—David Seymour, the ACT Party’s resident genius who thought, “You know what we need? A shiny new Treaty Principles Bill to "fix" all that pesky Māori-Crown partnership nonsense ...2 days ago

Strap yourselves in, folks, it’s time for another round of Arsehole of the Week, and this week’s golden derrière trophy goes to—drumroll, please—David Seymour, the ACT Party’s resident genius who thought, “You know what we need? A shiny new Treaty Principles Bill to "fix" all that pesky Māori-Crown partnership nonsense ...2 days ago - Bernard’s Dawn Chorus and Pick ‘n’ Mix for Monday, April 14

Apple Store, Shanghai. Trump wants all iPhones to be made in the USM but experts say that is impossible. Photo: Getty ImagesLong stories shortist from our political economy on Monday, April 14:Donald Trump’s exemption on tariffs on phones and computers is temporary, and he wants all iPhones made in the ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

Apple Store, Shanghai. Trump wants all iPhones to be made in the USM but experts say that is impossible. Photo: Getty ImagesLong stories shortist from our political economy on Monday, April 14:Donald Trump’s exemption on tariffs on phones and computers is temporary, and he wants all iPhones made in the ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - Unmasking the National Party’s Fascism

Kia ora, readers. It’s time to pull back the curtain on some uncomfortable truths about New Zealand’s political landscape. The National Party, often cloaked in the guise of "sensible centrism," has, at times, veered into territory that smells suspiciously like fascism. Now, before you roll your eyes and mutter about hyperbole, ...2 days ago

Kia ora, readers. It’s time to pull back the curtain on some uncomfortable truths about New Zealand’s political landscape. The National Party, often cloaked in the guise of "sensible centrism," has, at times, veered into territory that smells suspiciously like fascism. Now, before you roll your eyes and mutter about hyperbole, ...2 days ago - Open Letter to Auckland Transport about Project K

This is a letter we will be sending to Auckland Transport to ask they return to the original consulted plans on the Karanga-a-Hape Station precinct integration project, after they released significant changes to designs last week. If you would like to be added as a signatory, please reach out to ...Greater AucklandBy Connor Sharp2 days ago

This is a letter we will be sending to Auckland Transport to ask they return to the original consulted plans on the Karanga-a-Hape Station precinct integration project, after they released significant changes to designs last week. If you would like to be added as a signatory, please reach out to ...Greater AucklandBy Connor Sharp2 days ago - The gas plan that’s sailing Australia into strategic peril

Australia’s east coast is facing a gas crisis, as the country exports most of the gas it produces. Although it’s a major producer, Australia faces a risk of domestic liquefied natural gas (LNG) supply shortfalls ...The StrategistBy Henry Campbell and Raelene Lockhorst2 days ago

Australia’s east coast is facing a gas crisis, as the country exports most of the gas it produces. Although it’s a major producer, Australia faces a risk of domestic liquefied natural gas (LNG) supply shortfalls ...The StrategistBy Henry Campbell and Raelene Lockhorst2 days ago - Amateur Hour!

Overnight, Donald J. Trump, America’s 47th President, and only the second President since 1893 to win non-consecutive terms, rolled back more of his “no exemptions, no negotiations” & “no big deal” tariffs.Smartphones, computers, and other electronics1 are now exempt from the 125% levies imposed on imports from China; they retain ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī3 days ago

Overnight, Donald J. Trump, America’s 47th President, and only the second President since 1893 to win non-consecutive terms, rolled back more of his “no exemptions, no negotiations” & “no big deal” tariffs.Smartphones, computers, and other electronics1 are now exempt from the 125% levies imposed on imports from China; they retain ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī3 days ago - 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #15

A listing of 36 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, April 6, 2025 thru Sat, April 12, 2025. This week's roundup is again published by category and sorted by number of articles included in each. The formatting is a ...3 days ago

A listing of 36 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, April 6, 2025 thru Sat, April 12, 2025. This week's roundup is again published by category and sorted by number of articles included in each. The formatting is a ...3 days ago - World Domination

Just one year of loveIs better than a lifetime aloneOne sentimental moment in your armsIs like a shooting star right through my heartIt's always a rainy day without youI'm a prisoner of love inside youI'm falling apart all around you, yeahSongwriter: John Deacon.Morena folks, it feels like it’s been quite ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago

Just one year of loveIs better than a lifetime aloneOne sentimental moment in your armsIs like a shooting star right through my heartIt's always a rainy day without youI'm a prisoner of love inside youI'm falling apart all around you, yeahSongwriter: John Deacon.Morena folks, it feels like it’s been quite ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago - “I think I was, at that time, the only girl in Taranaki who ever wrote a line”

“It's a history of colonial ruin, not a history of colonial progress,” says Michele Leggott, of the Harris family.We’re talking about Groundwork: The Art and Writing of Emily Cumming Harris, in which she and Catherine Field-Dodgson recall a near-forgotten and fascinating life, the female speck in the history of texts.Emily’s ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago

“It's a history of colonial ruin, not a history of colonial progress,” says Michele Leggott, of the Harris family.We’re talking about Groundwork: The Art and Writing of Emily Cumming Harris, in which she and Catherine Field-Dodgson recall a near-forgotten and fascinating life, the female speck in the history of texts.Emily’s ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago - Fact brief – Is the sun responsible for global warming?

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Is the sun responsible for global warming? Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities, not solar variability, is responsible for the global warming observed ...3 days ago

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Is the sun responsible for global warming? Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities, not solar variability, is responsible for the global warming observed ...3 days ago - A Baptism in the Forest: Accepted

Hitherto, 2025 has not been great in terms of luck on the short story front (or on the personal front. Several acquaintances have sadly passed away in the last few days). But I can report one story acceptance today. In fact, it’s quite the impressive acceptance, being my second ‘professional ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2214 days ago

Hitherto, 2025 has not been great in terms of luck on the short story front (or on the personal front. Several acquaintances have sadly passed away in the last few days). But I can report one story acceptance today. In fact, it’s quite the impressive acceptance, being my second ‘professional ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2214 days ago - Bernard’s Saturday Soliloquy for the week to April 12

Six long stories short from our political economy in the week to Saturday, April 12:Donald Trump exploded a neutron bomb under 80 years of globalisation, but Nicola Willis said the Government would cut operational and capital spending even more to achieve a Budget surplus by 2027/28. That even tighter fiscal ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

Six long stories short from our political economy in the week to Saturday, April 12:Donald Trump exploded a neutron bomb under 80 years of globalisation, but Nicola Willis said the Government would cut operational and capital spending even more to achieve a Budget surplus by 2027/28. That even tighter fiscal ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - Budget 2025: delivering for whom?

On 22 May, the coalition government will release its budget for 2025, which it says will focus on "boosting economic growth, improving social outcomes, controlling government spending, and investing in long-term infrastructure.” But who, really, is this budget designed to serve? What values and visions for Aotearoa New Zealand lie ...4 days ago

On 22 May, the coalition government will release its budget for 2025, which it says will focus on "boosting economic growth, improving social outcomes, controlling government spending, and investing in long-term infrastructure.” But who, really, is this budget designed to serve? What values and visions for Aotearoa New Zealand lie ...4 days ago - The Other Side

Lovin' you has go to be (Take me to the other side)Like the devil and the deep blue sea (Take me to the other side)Forget about your foolish pride (Take me to the other side)Oh, take me to the other side (Take me to the other side)Songwriters: Steven Tyler, Jim ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago

Lovin' you has go to be (Take me to the other side)Like the devil and the deep blue sea (Take me to the other side)Forget about your foolish pride (Take me to the other side)Oh, take me to the other side (Take me to the other side)Songwriters: Steven Tyler, Jim ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago - It’s (past) time to get serious about funding Australia’s defence and security

In the week of Australia’s 3 May election, ASPI will release Agenda for Change 2025: preparedness and resilience in an uncertain world, a report promoting public debate and understanding on issues of strategic importance to ...The StrategistBy Marc Ablong4 days ago

In the week of Australia’s 3 May election, ASPI will release Agenda for Change 2025: preparedness and resilience in an uncertain world, a report promoting public debate and understanding on issues of strategic importance to ...The StrategistBy Marc Ablong4 days ago - The Downward Spiral of Arise Church: Part 4

Hi,Back in 2022 I spent a year reporting on New Zealand’s then-biggest megachurch, Arise, revealing the widespread abuse of hundreds of interns.That series led to a harrowing review (leaked by Webworm) and the resignation of its founders and leaders John and Gillian Cameron, who fled to Australia where they now ...David FarrierBy David Farrier4 days ago

Hi,Back in 2022 I spent a year reporting on New Zealand’s then-biggest megachurch, Arise, revealing the widespread abuse of hundreds of interns.That series led to a harrowing review (leaked by Webworm) and the resignation of its founders and leaders John and Gillian Cameron, who fled to Australia where they now ...David FarrierBy David Farrier4 days ago - Whatever the CCP says, regimes don’t have the rights of nations

All nation states have a right to defend themselves. But do regimes enjoy an equal right to self-defence? Is the security of a particular party-in-power a fundamental right of nations? The Chinese government is asking ...The StrategistBy John Fitzgerald5 days ago

All nation states have a right to defend themselves. But do regimes enjoy an equal right to self-defence? Is the security of a particular party-in-power a fundamental right of nations? The Chinese government is asking ...The StrategistBy John Fitzgerald5 days ago - Countervailing Trumpian Sense

A modest attempt to analyse Donald Trump’s tariff policies.Alfred Marshall, whose text book was still in use 40 years after he died wrote ‘every short statement about economics is misleading with the possible exception of my present one.’ (The text book is 719 pages.) It’s a timely reminder that any ...PunditBy Brian Easton5 days ago

A modest attempt to analyse Donald Trump’s tariff policies.Alfred Marshall, whose text book was still in use 40 years after he died wrote ‘every short statement about economics is misleading with the possible exception of my present one.’ (The text book is 719 pages.) It’s a timely reminder that any ...PunditBy Brian Easton5 days ago - Uncertainty, Hierarchy and the Dilemma of Democracy.

If nothing else, we have learned that the economic and geopolitical turmoil caused by the Trump tariff see-saw raises a fundamental issue of the human condition that extends beyond trade wars and “the markets.” That issue is uncertainty and its centrality to individual and collective life. It extends further into ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo5 days ago

If nothing else, we have learned that the economic and geopolitical turmoil caused by the Trump tariff see-saw raises a fundamental issue of the human condition that extends beyond trade wars and “the markets.” That issue is uncertainty and its centrality to individual and collective life. It extends further into ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo5 days ago - Strengthening South Korea’s national security by adopting the cloud

To improve its national security, South Korea must improve its ICT infrastructure. Knowing this, the government has begun to move towards cloud computing. The public and private sectors are now taking a holistic national-security approach ...The StrategistBy Afeeya Akhand5 days ago

To improve its national security, South Korea must improve its ICT infrastructure. Knowing this, the government has begun to move towards cloud computing. The public and private sectors are now taking a holistic national-security approach ...The StrategistBy Afeeya Akhand5 days ago - Workers’ Memorial Day 2025

28 April 2025 Mournfor theDead FightFor theLiving Every week in New Zealand 18 workers are killed as a consequence of work. Every 15 minutes, a worker suffers ...NZCTUBy Jeremiah Boniface5 days ago

28 April 2025 Mournfor theDead FightFor theLiving Every week in New Zealand 18 workers are killed as a consequence of work. Every 15 minutes, a worker suffers ...NZCTUBy Jeremiah Boniface5 days ago - Reset Pax Americana: the West needs a grand accord

The world is trying to make sense of the Trump tariffs. Is there a grand design and strategy, or is it all instinct and improvisation? But much more important is the question of what will ...The StrategistBy Michael Pezzullo5 days ago

The world is trying to make sense of the Trump tariffs. Is there a grand design and strategy, or is it all instinct and improvisation? But much more important is the question of what will ...The StrategistBy Michael Pezzullo5 days ago - Poisoning The Well – It’s Not Just ACT

OPINION:Yesterday was a triumphant moment in Parliament House.The “divisive”, “disingenous”, “unfair”, “discriminatory” and “dishonest” Treaty Principles Bill, advanced by the right wing ACT Party, failed.Spectacularly.11 MP votes for (ACT).112 MP votes against (All Other Parties).As the wonderful Te Pāti Māori MP, Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke said: We are not divided, but united.Green ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī5 days ago

OPINION:Yesterday was a triumphant moment in Parliament House.The “divisive”, “disingenous”, “unfair”, “discriminatory” and “dishonest” Treaty Principles Bill, advanced by the right wing ACT Party, failed.Spectacularly.11 MP votes for (ACT).112 MP votes against (All Other Parties).As the wonderful Te Pāti Māori MP, Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke said: We are not divided, but united.Green ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī5 days ago - The Pacific Response Group is making pleasing progress but needs more buy-in

The Pacific Response Group (PRG), a new disaster coordination organisation, has operated through its first high-risk weather season. But as representatives from each Pacific military leave Brisbane to return to their home countries for the ...The StrategistBy Blake Johnson and Adam Ziogas5 days ago

The Pacific Response Group (PRG), a new disaster coordination organisation, has operated through its first high-risk weather season. But as representatives from each Pacific military leave Brisbane to return to their home countries for the ...The StrategistBy Blake Johnson and Adam Ziogas5 days ago - Friday 11 April

The Treaty Principles Bill has been defeated in Parliament with 112 votes in opposition and 11 in favour, but the debate about Te Tiriti and Māori rights looks set to stay high on the political agenda. Supermarket giant Woolworths has confirmed a new operating model that Workers First say will ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald5 days ago

The Treaty Principles Bill has been defeated in Parliament with 112 votes in opposition and 11 in favour, but the debate about Te Tiriti and Māori rights looks set to stay high on the political agenda. Supermarket giant Woolworths has confirmed a new operating model that Workers First say will ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald5 days ago - A few wins, for now

More Than A FeildingBy David Slack5 days ago

- Aotearoa Wins!

And this is what I'm gonna doI'm gonna put a call to you'Cause I feel good tonightAnd everything's gonna beRight-right-rightI'm gonna have a good time tonightRock and roll music gonna play all nightCome on, baby, it won't take longOnly take a minute just to sing my songSongwriters: Kirk Pengilly / ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago

And this is what I'm gonna doI'm gonna put a call to you'Cause I feel good tonightAnd everything's gonna beRight-right-rightI'm gonna have a good time tonightRock and roll music gonna play all nightCome on, baby, it won't take longOnly take a minute just to sing my songSongwriters: Kirk Pengilly / ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago - Indonesia’s cyber soldiers: armed without a compass

The Indonesian military has a new role in cybersecurity but, worryingly, no clear doctrine on what to do with it nor safeguards against human rights abuses. Assignment of cyber responsibility to the military is part ...The StrategistBy Gatra Priyandita and Christian Guntur Lebang5 days ago

The Indonesian military has a new role in cybersecurity but, worryingly, no clear doctrine on what to do with it nor safeguards against human rights abuses. Assignment of cyber responsibility to the military is part ...The StrategistBy Gatra Priyandita and Christian Guntur Lebang5 days ago - Weekly Roundup 11-April-2025

Another Friday, another roundup. Autumn is starting to set in, certainly getting darker earlier but we hope you enjoy some of the stories we found interesting this week. This week in Greater Auckland On Tuesday we ran a guest post from the wonderful Darren Davis about what’s happening ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland5 days ago

Another Friday, another roundup. Autumn is starting to set in, certainly getting darker earlier but we hope you enjoy some of the stories we found interesting this week. This week in Greater Auckland On Tuesday we ran a guest post from the wonderful Darren Davis about what’s happening ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland5 days ago - Bernard’s Dawn Chorus & Pick ‘n’ Mix Six for Friday, April 11

Long stories shortest: The White House confirms Donald Trump’s total tariffs now on China are 145%, not 125%. US stocks slump again. Gold hits a record high. PM Christopher Luxon joins a push for a new rules-based trading system based around CPTPP and EU, rather than US-led WTO. Winston Peters ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

Long stories shortest: The White House confirms Donald Trump’s total tariffs now on China are 145%, not 125%. US stocks slump again. Gold hits a record high. PM Christopher Luxon joins a push for a new rules-based trading system based around CPTPP and EU, rather than US-led WTO. Winston Peters ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - The Hoon around the week to April 11

The podcast above of the weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers on Thursday night features co-hosts & talking about the week’s news with regular and special guests, including: and on the week in geopolitics and climate, including Donald Trump’s shock and (partial) backflip; and,Health Coalition Aotearoa Chair ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

The podcast above of the weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers on Thursday night features co-hosts & talking about the week’s news with regular and special guests, including: and on the week in geopolitics and climate, including Donald Trump’s shock and (partial) backflip; and,Health Coalition Aotearoa Chair ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - Skeptical Science New Research for Week #15 2025

Open access notables Global and regional drivers for exceptional climate extremes in 2023-2024: beyond the new normal, Minobe et al., npj Climate and Atmospheric Science: Climate records have been broken with alarming regularity in recent years, but the events of 2023–2024 were exceptional even when accounting for recent climatic trends. ...6 days ago

Open access notables Global and regional drivers for exceptional climate extremes in 2023-2024: beyond the new normal, Minobe et al., npj Climate and Atmospheric Science: Climate records have been broken with alarming regularity in recent years, but the events of 2023–2024 were exceptional even when accounting for recent climatic trends. ...6 days ago - The US harms its image in the Pacific with aid cuts and tariffs

USAID cuts and tariffs will harm the United States’ reputation in the Pacific more than they will harm the region itself. The resilient region will adjust to the economic challenges and other partners will fill ...The StrategistBy Blake Johnson and Astrid Young6 days ago

USAID cuts and tariffs will harm the United States’ reputation in the Pacific more than they will harm the region itself. The resilient region will adjust to the economic challenges and other partners will fill ...The StrategistBy Blake Johnson and Astrid Young6 days ago - Good fucking riddance

National's racist and divisive Treaty Principles Bill was just voted down by the House, 112 to 11. Good fucking riddance. The bill was not a good-faith effort at legislating, or at starting a "constitutional conversation". Instead it was a bad faith attempt to stoke division and incite racial hatred - ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago

National's racist and divisive Treaty Principles Bill was just voted down by the House, 112 to 11. Good fucking riddance. The bill was not a good-faith effort at legislating, or at starting a "constitutional conversation". Instead it was a bad faith attempt to stoke division and incite racial hatred - ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago - The threat spectrum

Democracy watch Indonesia’s parliament passed revisions to the country’s military law, which pro-democracy and human rights groups view as a threat to the country’s democracy. One of the revisions seeks to expand the number of ...The StrategistBy Linus Cohen, Astrid Young and Alice Wai6 days ago

Democracy watch Indonesia’s parliament passed revisions to the country’s military law, which pro-democracy and human rights groups view as a threat to the country’s democracy. One of the revisions seeks to expand the number of ...The StrategistBy Linus Cohen, Astrid Young and Alice Wai6 days ago - Australia needs a civilian cyber reserve. State emergency services are the model

Australia should follow international examples and develop a civilian cyber reserve as part of a whole-of-society approach to national defence. By setting up such a reserve, the federal government can overcome a shortage of expertise ...The StrategistBy Samuli Haataja and Dan Svantesson6 days ago

Australia should follow international examples and develop a civilian cyber reserve as part of a whole-of-society approach to national defence. By setting up such a reserve, the federal government can overcome a shortage of expertise ...The StrategistBy Samuli Haataja and Dan Svantesson6 days ago

Related Posts

- Release: Food prices further stretching the family budget

Families already stretched by rising costs will struggle with the news food prices are going up again. ...21 hours ago

Families already stretched by rising costs will struggle with the news food prices are going up again. ...21 hours ago - Release: Mental health staff and patients at risk without plan

More people could be harmed if Minister for Mental Health Matt Doocey does not guarantee to protect patients and workers as the Police withdraw from supporting mental health call outs. ...2 days ago

More people could be harmed if Minister for Mental Health Matt Doocey does not guarantee to protect patients and workers as the Police withdraw from supporting mental health call outs. ...2 days ago - Release: Driver licensing proposal doesn’t put safety first

The Government’s proposal to change driver licensing rules is a mixed bag of sensible and careless. ...2 days ago

The Government’s proposal to change driver licensing rules is a mixed bag of sensible and careless. ...2 days ago - Release: Students struggling as Govt sits on hands

The Government is continuing to sit on its hands as students struggle to pay rent due to delays with StudyLink. ...5 days ago

The Government is continuing to sit on its hands as students struggle to pay rent due to delays with StudyLink. ...5 days ago - Release: More must be done to stop children going hungry

More children are going hungry and statistics showing children in material hardship continue to get worse. ...5 days ago

More children are going hungry and statistics showing children in material hardship continue to get worse. ...5 days ago - Greens continue to call for Pacific Visa Waiver

The Green Party recognises the extension of visa allowances for our Pacific whānau as a step in the right direction but continues to call for a Pacific Visa Waiver. ...5 days ago

The Green Party recognises the extension of visa allowances for our Pacific whānau as a step in the right direction but continues to call for a Pacific Visa Waiver. ...5 days ago - More children going hungry under Coalition govt

The Government yesterday released its annual child poverty statistics, and by its own admission, more tamariki across Aotearoa are now living in material hardship. ...5 days ago

The Government yesterday released its annual child poverty statistics, and by its own admission, more tamariki across Aotearoa are now living in material hardship. ...5 days ago - Release: Longer wait for treatment under National

New Zealanders have waited longer to get an appointment with a specialist and to get elective surgery under the National Government. ...5 days ago

New Zealanders have waited longer to get an appointment with a specialist and to get elective surgery under the National Government. ...5 days ago - Ka mate te Pire- Ka ora te mana o Te Tiriti o Waitangi me te iwi Māori

Today, Te Pāti Māori join the motu in celebration as the Treaty Principles Bill is voted down at its second reading. “From the beginning, this Bill was never welcome in this House,” said Te Pāti Māori Co-Leader, Rawiri Waititi. “Our response to the first reading was one of protest: protesting ...6 days ago

Today, Te Pāti Māori join the motu in celebration as the Treaty Principles Bill is voted down at its second reading. “From the beginning, this Bill was never welcome in this House,” said Te Pāti Māori Co-Leader, Rawiri Waititi. “Our response to the first reading was one of protest: protesting ...6 days ago - Chris Hipkins speech: Treaty Principles Bill second reading

Normally, when I rise in this House to speak on a bill, I say it's a great privilege to speak on the bill. That is not the case today. ...6 days ago

Normally, when I rise in this House to speak on a bill, I say it's a great privilege to speak on the bill. That is not the case today. ...6 days ago - Release: End to the Treaty Principles Bill, but challenges remain ahead for Aotearoa

6 days ago

- Ka mate te Pire, ka ora Te Tiriti o Waitangi – Treaty Principles Bill dead, Te Tiriti o Waitangi m...

The Green Party is proud to have voted down the Coalition Government’s Treaty Principles Bill, an archaic piece of legislation that sought to attack the nation’s founding agreement. ...6 days ago

The Green Party is proud to have voted down the Coalition Government’s Treaty Principles Bill, an archaic piece of legislation that sought to attack the nation’s founding agreement. ...6 days ago - Member’s Bill an opportunity for climate action

A Member’s Bill in the name of Green Party MP Julie Anne Genter which aims to stop coal mining, the Crown Minerals (Prohibition of Mining) Amendment Bill, has been pulled from Parliament’s ‘biscuit tin’ today. ...6 days ago

A Member’s Bill in the name of Green Party MP Julie Anne Genter which aims to stop coal mining, the Crown Minerals (Prohibition of Mining) Amendment Bill, has been pulled from Parliament’s ‘biscuit tin’ today. ...6 days ago - Release: Bill to make trading laws fairer passes first hurdle

Labour MP Kieran McAnulty’s Members Bill to make the law simpler and fairer for businesses operating on Easter, Anzac and Christmas Days has passed its first reading after a conscience vote in Parliament. ...6 days ago

Labour MP Kieran McAnulty’s Members Bill to make the law simpler and fairer for businesses operating on Easter, Anzac and Christmas Days has passed its first reading after a conscience vote in Parliament. ...6 days ago - Release: Reserve Bank acts while Govt shrugs

Nicola Willis continues to sit on her hands amid a global economic crisis, leaving the Reserve Bank to act for New Zealanders who are worried about their jobs, mortgages, and KiwiSaver. ...7 days ago

Nicola Willis continues to sit on her hands amid a global economic crisis, leaving the Reserve Bank to act for New Zealanders who are worried about their jobs, mortgages, and KiwiSaver. ...7 days ago - Release: Property Law Amendment Bill pulled from ballot

A Bill to protect first home buyers and others from bad faith property vendors has been drawn from the Member’s Ballot. ...1 week ago

A Bill to protect first home buyers and others from bad faith property vendors has been drawn from the Member’s Ballot. ...1 week ago - Release: More children at risk of losing family connections

Karen Chhour is proposing to scrap Oranga Tamariki targets which aim to connect more children under state care with family and their culture. ...1 week ago

Karen Chhour is proposing to scrap Oranga Tamariki targets which aim to connect more children under state care with family and their culture. ...1 week ago - Release: David Parker made a difference – Hipkins

The Labour Leader today acknowledged and celebrated David Parker’s 23-year contribution to the Labour Party and to Parliament. ...1 week ago

The Labour Leader today acknowledged and celebrated David Parker’s 23-year contribution to the Labour Party and to Parliament. ...1 week ago - Release: David Parker to step down from Parliament

Long-serving Labour MP and former Minister David Parker has today announced his intention to leave Parliament. ...1 week ago

Long-serving Labour MP and former Minister David Parker has today announced his intention to leave Parliament. ...1 week ago - Release: Flaws in Govt’s climate strategy will cost us money

The Government’s plan to achieve our climate goals falls short, and will cost New Zealanders money and jobs. ...1 week ago

The Government’s plan to achieve our climate goals falls short, and will cost New Zealanders money and jobs. ...1 week ago - Green Party differing view on the Treaty Principles Bill

1 week ago

- Te Pāti Māori Urges Governor-General to Block Repeal of 7AA

Today, the Oranga Tamariki (Repeal of Section 7AA) Amendment Bill has passed its third and final reading, but there is one more stage before it becomes law. The Governor-General must give their ‘Royal assent’ for any bill to become legally enforceable. This means that, even if a bill gets voted ...2 weeks ago

Today, the Oranga Tamariki (Repeal of Section 7AA) Amendment Bill has passed its third and final reading, but there is one more stage before it becomes law. The Governor-General must give their ‘Royal assent’ for any bill to become legally enforceable. This means that, even if a bill gets voted ...2 weeks ago - Release: Abortion care quietly shelved amid staff shortage

Abortion care at Whakatāne Hospital has been quietly shelved, with patients told they will likely have to travel more than an hour to Tauranga to get the treatment they need. ...2 weeks ago

Abortion care at Whakatāne Hospital has been quietly shelved, with patients told they will likely have to travel more than an hour to Tauranga to get the treatment they need. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Govt guts Kāinga Ora, third of workforce under axe

The gutting of Kāinga Ora shows public housing is not a priority for this Government as it removes a third of the roles at the housing agency. ...2 weeks ago

The gutting of Kāinga Ora shows public housing is not a priority for this Government as it removes a third of the roles at the housing agency. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Thousands of submissions excluded from Treaty Principles Bill report

Thousands of New Zealanders’ submissions are missing from the official parliamentary record because the National-dominated Justice Select Committee has rushed work on the Treaty Principles Bill. ...2 weeks ago

Thousands of New Zealanders’ submissions are missing from the official parliamentary record because the National-dominated Justice Select Committee has rushed work on the Treaty Principles Bill. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Uncertainty remains over the impact of tariffs

Today’s announcement of 10 percent tariffs for New Zealand goods entering the United States is disappointing for exporters and consumers alike, with the long-lasting impact on prices and inflation still unknown. ...2 weeks ago

Today’s announcement of 10 percent tariffs for New Zealand goods entering the United States is disappointing for exporters and consumers alike, with the long-lasting impact on prices and inflation still unknown. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Worst February for building consents in over a decade

The National Government’s choices have contributed to a slow-down in the building sector, as thousands of people have lost their jobs in construction. ...2 weeks ago

The National Government’s choices have contributed to a slow-down in the building sector, as thousands of people have lost their jobs in construction. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Labour supports Willie Apiata’s selfless act

Willie Apiata’s decision to hand over his Victoria Cross to the Minister for Veterans is a powerful and selfless act, made on behalf of all those who have served our country. ...2 weeks ago

Willie Apiata’s decision to hand over his Victoria Cross to the Minister for Veterans is a powerful and selfless act, made on behalf of all those who have served our country. ...2 weeks ago - Te Pāti Māori MPs Denied Fundamental Rights in Privileges Committee Hearing

The Privileges Committee has denied fundamental rights to Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, Rawiri Waititi and Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke, breaching their own standing orders, breaching principles of natural justice, and highlighting systemic prejudice and discrimination within our parliamentary processes. The three MPs were summoned to the privileges committee following their performance of a haka ...2 weeks ago

The Privileges Committee has denied fundamental rights to Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, Rawiri Waititi and Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke, breaching their own standing orders, breaching principles of natural justice, and highlighting systemic prejudice and discrimination within our parliamentary processes. The three MPs were summoned to the privileges committee following their performance of a haka ...2 weeks ago - Release: Govt health and safety changes put workers at risk

Changes to New Zealand’s health and safety laws will strip back key protections for small businesses and put working Kiwis at greater risk. ...2 weeks ago

Changes to New Zealand’s health and safety laws will strip back key protections for small businesses and put working Kiwis at greater risk. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Kiwis worse off this April thanks to Govt choices

April 1 used to be a day when workers could count on a pay rise with stronger support for those doing it tough, but that’s not the case under this Government. ...2 weeks ago

April 1 used to be a day when workers could count on a pay rise with stronger support for those doing it tough, but that’s not the case under this Government. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Three more years for Interislander ferries

Winston Peters is shopping for smaller ferries after Nicola Willis torpedoed the original deal, which would have delivered new rail enabled ferries next year. ...2 weeks ago

Winston Peters is shopping for smaller ferries after Nicola Willis torpedoed the original deal, which would have delivered new rail enabled ferries next year. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Myanmar junta must stop the airstrikes

The Government should work with other countries to press the Myanmar military regime to stop its bombing campaign especially while the country recovers from the devastating earthquake. ...2 weeks ago

The Government should work with other countries to press the Myanmar military regime to stop its bombing campaign especially while the country recovers from the devastating earthquake. ...2 weeks ago - Release: National failing to deliver on supermarkets

National is paying lip service to its promises to bring down the cost of living, failing to make any meaningful change in the grocery sector. ...2 weeks ago

National is paying lip service to its promises to bring down the cost of living, failing to make any meaningful change in the grocery sector. ...2 weeks ago

Related Posts

- Why the Coalition’s tone-deaf diss track was bound to hit all the wrong notes

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Andy Ward, Senior Lecturer in Music, School of Business and Creative Industries, University of the Sunshine Coast Hip-hop is a cultural powerhouse that has infiltrated every facet of popular culture, across a global market. That said, one place you usually don’t see ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation7 minutes ago

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Andy Ward, Senior Lecturer in Music, School of Business and Creative Industries, University of the Sunshine Coast Hip-hop is a cultural powerhouse that has infiltrated every facet of popular culture, across a global market. That said, one place you usually don’t see ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation7 minutes ago - Homelessness – the other housing crisis politicians aren’t talking about

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Cameron Parsell, Professor, School of Social Science, The University of Queensland Igor Corovic/Shutterstock Measures to tackle homelessness in Australia have been conspicuously absent from the election campaign. The major parties have rightly identified deep voter anxiety over high house prices. They ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation1 hour ago

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Cameron Parsell, Professor, School of Social Science, The University of Queensland Igor Corovic/Shutterstock Measures to tackle homelessness in Australia have been conspicuously absent from the election campaign. The major parties have rightly identified deep voter anxiety over high house prices. They ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation1 hour ago - Superb fairy-wrens’ songs hold clues to their personalities, new study finds

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Diane Colombelli-Négrel, Senior Lecturer, Animal Behaviour, Flinders University Two superb fairy-wrens (_Malurus cyaneus_). ARKphoto/Shutterstock When we think of bird songs, we often imagine a cheerful soundtrack during our morning walks. However, for birds, songs are much more than background music – they ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation2 hours ago

- ‘De-extinction’ of dire wolves promotes false hope: technology can’t undo extinction

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Martín Boer-Cueva, Ecologist and Environmental Consultant, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Colossal Biosciences Over the past week, the media have been inundated with news of the “de-extinction” of the dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus) – a species that went extinct about 13,000 years ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation2 hours ago

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Martín Boer-Cueva, Ecologist and Environmental Consultant, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Colossal Biosciences Over the past week, the media have been inundated with news of the “de-extinction” of the dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus) – a species that went extinct about 13,000 years ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation2 hours ago - The tiniest rebuild in Ōtautahi is finally complete

For the last four years, one artist has been rebuilding the lost icons of the city in miniature form. It’s a Friday morning and Mike Beer, aka Ghostcat, is flitting about Pūmanawa Gallery in Ōtautahi making last-minute adjustments. “These are actually from the Canterbury sale yards,” he says, gesturing to ...The SpinoffBy Alex Casey2 hours ago

For the last four years, one artist has been rebuilding the lost icons of the city in miniature form. It’s a Friday morning and Mike Beer, aka Ghostcat, is flitting about Pūmanawa Gallery in Ōtautahi making last-minute adjustments. “These are actually from the Canterbury sale yards,” he says, gesturing to ...The SpinoffBy Alex Casey2 hours ago - ‘Makes me feel better about humanity’: Hannah Tunnicliffe’s favourite writer

Welcome to The Spinoff Books Confessional, in which we get to know the reading habits of Aotearoa writers, and guests. This week: Hannah Tunnicliffe, author of new mystery book for children Detective Stanley and the Mystery at the Museum (illustrated by Erica Harrison). The book I wish I’d written Anything ...The SpinoffBy The Spinoff Review of Books2 hours ago

Welcome to The Spinoff Books Confessional, in which we get to know the reading habits of Aotearoa writers, and guests. This week: Hannah Tunnicliffe, author of new mystery book for children Detective Stanley and the Mystery at the Museum (illustrated by Erica Harrison). The book I wish I’d written Anything ...The SpinoffBy The Spinoff Review of Books2 hours ago - Students are neither left nor right brained: how some early childhood educators get this ‘neuromyt...

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Kate E. Williams, Professor of Education, University of the Sunshine Coast MalikNalik/ Shutterstock Many teachers and parents know neuroscience, the study of how the brain functions and develops, is important for children’s education. Brain development is recommended as part of ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation3 hours ago

Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Kate E. Williams, Professor of Education, University of the Sunshine Coast MalikNalik/ Shutterstock Many teachers and parents know neuroscience, the study of how the brain functions and develops, is important for children’s education. Brain development is recommended as part of ...Evening ReportBy The Conversation3 hours ago - Reserve Bank’s budget to be slashed by 25%

3 hours ago

- Review: The Polkinghorne documentary and what the trial was missing