It is seven years since Crystal Palace Transition Town (CPTT) set up the Crystal Palace Food Market. It has gone on to win many awards as one of London’s finest food markets. They have built a new infrastructure, a family of traders, and sparked a more resilient food system, connecting traders, customers, food producers and growers close to, and within, the city. When COVID-19 arrived, the market team had to take the tough call whether to stay open or to close.

As the UK government was just beginning to consider how it might respond to COVID-19, CPTT, and Karen and Laura in the CP Food Market team, were ahead of government guidance, by weeks. The food market introduced social distancing way ahead of government guidance, to some customers’ bafflement. First they went to creating barriers to reduce transmission, then social distancing queues, then stricter queues with rather fetching circles painted on the pavement at 2 metre intervals, then changed the model to having different stalls on different days. Their website was rapidly overhauled to become a portal so regulars could order home deliveries from their favourite suppliers.

Crystal Palace Food Market

CPTT have spent 10 years building extensive networks of projects and organisations, while also starting to lay down a new infrastructure of initiatives that are modelling what a low carbon future will need to look like, showing a level of ambition and imagination that, as with the example above, is way ahead of government action and which highlights the poverty of creativity among those making the larger decisions.

What if the rest of the city had locked down with that same sense of urgency? Who knows how many lives would have been saved. If our collective approach to climate change showed the same respect for science, the same focused sense of purpose, creativity and leadership, how different would it look? COVID-19 is, after all, merely a tragic foreshadowing of what uncontrolled climate change will look like and, indeed, how it is already being experienced by many, particularly in the Global South.

Before we go on to look at what Transition groups are doing on the ground, a quick reality check. We know that to have any chance of staying below 1.5 degrees of global heating requires huge changes. We know that the changes we have seen during the lockdown have led to cuts of just 5.5% globally this year, and that what is actually needed, according to the UN, is cuts of 7.6% every year, starting now. What COVID-19 has shown us is that things can change fast, we can build new infrastructures very fast if needed, that communities are capable of amazing acts of mutual support, and of reimagining the future in ways that many in current positions of leadership appear unable to.

George Monbiot recently wrote a piece that spoke to the growing calls to #BuildBackBetter. He argued we should “Bail out the people, not the corporations. Bail out the living world, not its destroyers. Let’s not waste our second chance”. Central to the Transition movement from the outset has been the idea of resilience. Usually framed as the ability to ‘bounce back’, it is seen in the Transition movement as being better imagined as the capacity to ‘bounce forward’, i.e. to use it as the opportunity to move forward to something better. How then to ‘bounce forward’ from COVID-19 in such a way that we also move to a way of doing things consistent with the scale of the climate crisis?

The Transition movement has been an experiment focused around this question for almost 13 years now. So what is it? Transition Network refers to it as “a movement of communities that are reimagining and rebuilding the world”. Transition groups work with a particular set of principles. They:

- Respect resource limits and create resilience

- Promote inclusivity and social justice

- Adopt subsidiarity (self-organisation and decision making at the appropriate level)

- Pay attention to balance, creating space for reflection, celebration and rest to balance the times when we’re busily getting things done.

- Are part of an experimental, learning network, seeing Transition as a real-life, real-time global social experiment.

- Freely share ideas and power, a grassroots movement where ideas can be taken up rapidly, widely and effectively because each community takes ownership of the process themselves

- Collaborate and look for synergies

- Foster positive visioning and creativity

It is true that there is much here that governments can do and must do, hence the need for movements such as Extinction Rebellion to bring sufficient pressure to bear. But as communities, as neighbourhoods, streets, workplaces, community organisations, there is so much we can do. Things that governments and other top-down institutions seem unable to even dream of. Indeed COVID-19 has shown that while many governments have taken their time (with a handful, like New Zealand, showing what a more mature approach could look like), communities have come together, organised remarkable networks and support infrastructure in very little time (something Transition Town Media (US) reflect on here).

As in Crystal Palace, around the world it has often been the communities leading the way, organising in ways that governments, so far away from what’s happening on the ground, wouldn’t even know where to begin. The idea of this piece is to give you a taste of that. The stories we share here are just a small taste of what is actually happening on the ground in the more than 50 countries where Transition groups are active.

What have we seen from the Transition movement during this time, and before, that can shape our thinking as to what ‘bouncing forward’ might look like in practice?

Let’s start with food. Many Transition groups have been responding to the COVID19 crisis in emergency mode.

The Deal with It group in Deal (UK) have joined forces with other local groups and been working with local farmers, bringing volunteers to do ‘gleaning’, harvesting surplus that is uneconomic for the farmer to bother with. Last week they gleaned 3 tonnes of fresh produce in a week which was distributed to food banks and families in food need, while also maintaining their food garden beds on the local train station.

Gleaning in Kent

In the US, Transition Town Glassboro have taken to Zoom to run online food growing classes, as have Transition Wellington in the UK. Transition Town Port Washington in the US have been running online composting classes. Cooperation Humboldt (US) have been creating ‘Little Free Pantries’ for people to help themselves to donated food. They have also been building small food gardens for families in need, with over 90 requests so far. Transition Wilmslow are finding a lot more people want to get involved in their community allotment and are now planning a new, much larger, market garden.

Cooperation Humboldt Little Free Pantries in Eureka

Transition Loughborough’s community allotment has also been in full swing, and they have been mastering the art of social distancing on an allotment, while also having ‘virtual’ plant sales (with an honesty box and dropping plants at peoples’ front doors). Transition Town Bridport (UK) had been planning a day planting an edible hedge at the local St. Mary’s School. It was going to be a community day with tea, cake, and planting. But COVID-19 had different ideas, and instead the planting had to be done by a group of just 5 members who managed to plant the entire hedge, which included apples, pears, plums, figs, cherries and nut varieties whilst also maintaining social distancing. Sarah Wilberforce of TTB said “the hedge will create beautiful blossom in the Spring, and foraging of nuts and berries in the autumn.”

In Totnes, ‘Food In Community’ have been gathering grade-out food from Riverford Organic Farm (vegetables and fruit with blemishes or imperfections) and distributing them to organisations and people in food need. So far they have distributed over 8 tonnes of produce. As Chantelle Norton from the group told me, “it’s about people dignity, community food sovereignty and resilience”. The networks and partnerships that they had laid in advance of this crisis have proved invaluable in this new context.

While these projects are proving vital in the context of COVID19, how do they point a way forward to what comes next? To ‘bouncing forward’? Where do we see these projects taking concrete steps towards the building of new food systems and networks, to a reimagining of the food system? In Sweden, the Transition group in Soderhamn called Närjord (“local soil”) have started a campaign called Potatisuppropet (‘Potato Appeal’, or ‘Potato Uprising’). COVID19 highlighted the perilous decline in food self sufficiency in Sweden, now down to just 50%.

They were inspired by the story from Swedish history of the 1917 Potato Uprising where, during the First World War, with famines looming, a quarter of a million people, mainly women, took to the streets to demand food. The government gave out seeds and seed potatoes and food gardens sprang up everywhere. Advertising posters from the times carried the immortal slogan “everyone plants potatoes – except boring people”.

Potatisuppropet

In the face of COVID19, the Swedish government stated “it is not possible to build food security in a few weeks’ time”. As Pella Thiel of the Swedish Transition Hub writes, “the Transition movement begs to differ”. The Närjord group bought 12 tonnes of seed potatoes, sold shares of the future harvest and gave away seed potatoes. They met with local authorities to instigate a more proactive approach to food security. The Swedish Hub then took the idea and rolled it out across Sweden as a simple idea. Firstly, plant a potato, secondly, tell the world about it, and thirdly ask your local authority what it is doing for food security. The response has been overwhelming.

Potatoes have been popping up in buckets outside local government offices and town squares. There has been a massive sharing of potato-growing techniques, potato songs, potato slogans. This simple act is also working hard to build a bridge to what the post-COVID world could look like. A very similar scheme is being promoted by Mantois en Transition in France as ‘Operation Potatoes’.

In Wales, Transition Llandrindod Wells just heard they got funding from the Lottery to create ‘Incredible Edible Llandrindod’. As Dorienne Robinson from the group put it, “We want to try and grow as much food throughout the town as possible. To this end we have liaised with Powys County Council who have been hugely helpful and allowed us to start our project on a disused tennis court in the centre of town. A large variety of vegetables and fruits will be grown in planters and would be for the public to pick and use. If successful the Council may be able to offer us more space.”

How is COVID-19 affecting one of the most ambitious food projects to emerge from the Transition movement, namely Ceinture Aliment-terre Liégeoise (the Liége Food Belt)? CATL is reimagining the food system for the city, co-ordinating 21 co-operatives ranging from vineyards and breweries to shops and delivery businesses. I asked Christian Jonet of CATL how COVID-19 had impacted their work. He told me it has led to a significant increase in demand for local food. “Most of the cooperatives in our network that accept online orders have seen their turnover triple in a couple of months”, he told me. This has required a lot of reorganisation, and reinforced the need for a new central logistics hub. On the downside however, other CATL projects such as the creation of sustainable chains in the city’s schools have been put on hold. The closure of the city’s restaurants have also been a big blow. CATL co-ops such as Rayon 9, the cooperative that makes deliveries by bicycle, has lost 80% of its customers – mainly restaurants. However, the increase in demand for deliveries for the other co-ops offset this. As Christian put it, “it’s hard to imagine what the future will look like, but for now, consumer demand for local products is exploding”.

The past 12 years of the Transition movement is rich with learnings that can inform the discussions about ‘bouncing forward’. Groups have created new markets, connected farmers and growers with urban populations, created new vibrant CSA farms, created detailed studies analysing the degree to which places could feed themselves. They have put in place new mills, have crowdfunded for new food businesses, created new food gardens in schools, done economic analyses of the impacts a shift towards more localised food chains would bring. How differently would we be thinking about food resilience and vulnerability now if those strategies had been more widely adopted and properly resourced?

Connecting and mutual support

If we believed Hollywood disaster movies, by now society should have unravelled and broken down. Yet what has emerged is a strong instinct for solidarity and mutual support, an amazing flowering of people coming together to support each other, and to support essential workers in their community. Transition groups have played their part, as have many individual Transitioners, and not always necessarily ‘badged’ as Transition. As Hilary Jennings of Transition Town Tooting told me, “there is tons more going on where people are working to make PPE, campaigning for safer streets post lockdown, volunteering in street mutual aid groups, etc. In Tooting there is a flowering of a real diversity of community responses involving lots of interconnected individuals and groups rather than a ‘Transition-led’ response”.

But at the same time, Transition groups are stepping up to provide connection and reflection during these times. Transition Network itself has held ‘Connecting Transitions’ Zoom calls, and many Hubs, such as the Belgian Hub Reseau Transition have also been creating and holding spaces for reflection and sharing. Transition Buxton (UK) have been holding online webinars exploring what ‘bouncing forward’ could mean in their local context.

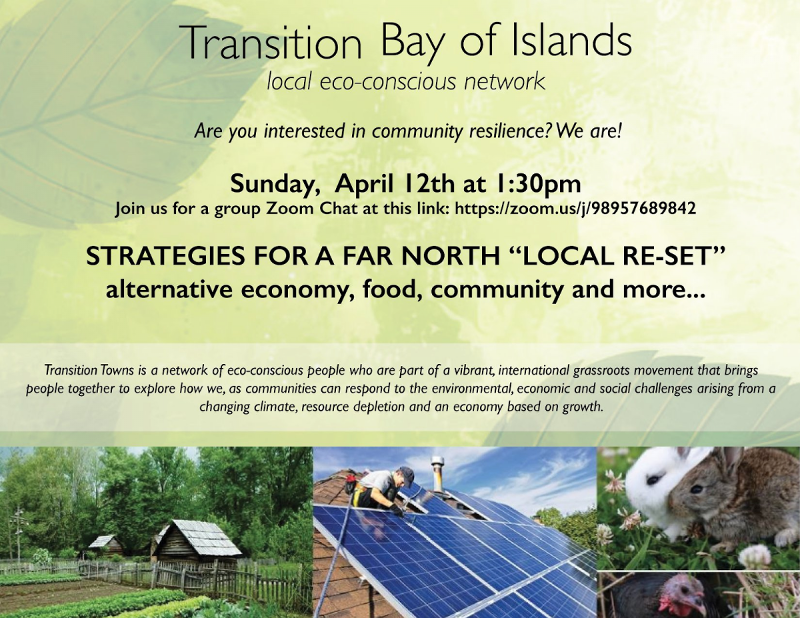

Transition Bay of Islands (New Zealand) have been doing the same, writing “We will need to ground ourselves. We will need to take stock of everything, reassess our lives individually and collectively, and then begin rebuilding consciously together, the kind of world we want to live in and how we want to live in it. So, let’s have some discussion around strategies for this ‘reset’ in our local Far North community”.

The Transition Australia Hub have been coordinating a series of weekly Zoom ‘conversation cafes’, and recently circulated a colourful note of insights shared. Transition Town Jericho in the US have been using Zoom to facilitate workshops around how to work with grief in this time. The Luxembourg Hub have been running online Resilience Cafes. Transition Sweden’s first webinar responding to Covid-19 attracted 800 participants and has since been viewed by over 5,000. Over the Easter weekend, the German Transition Hub ran a three day open web-conference under the name Beyond Corona. As they report, “the theme was co-dreaming, co-creating, co living”.

In Belgium, the national Hub, Reseau Transition, did something similar, but inviting people from a wide range of other movements too. As Josué Dusoulier of the group put it, the event, called ‘Time to Breathe’ was attended by 100 people. He continues, “breathe so that we don’t go back to business as usual after this crisis. Breathe so that we’re able to see what potential is here and be able to make deeper steps in the changes we need”. This model of Zoom meetings exploring how we are and what happens next has also been picked up by many other Hubs and local groups.

Resilient local economies

COVID-19 is also causing more people to question what an economy is for. What, they are asking, should we be valuing and seeking to protect, what activities are essential to our ability to sustain lives and livelihoods, create and maintain wellbeing? Transition Liverpool (UK) are working on a solidarity economy map of the city and its wider region with, as they write, “an initial focus on the small businesses that will really need support to survive the social distancing model”. They also just got £50,000 of funding to run (once the lockdown is lifted) a ‘Park(ing) Day’ event, where they take over car parking spaces across the city (making sure they buy a ticket first) and turning them into something that gives a flavour of what comes after the age of the car.

Back in Crystal Palace, COVID-19 has meant a big rethink for their hugely successful ‘Library of Things’ project. No longer able to be a Library of Things in the way originally conceived, i.e. people dropping by to borrow tools and equipment, the group have developed a ‘Library of People’, an online skills sharing platform, as well as ‘Things on Wheels’, a door to door delivery service for things people want to borrow.

Transition groups are also playing an active role in creating new infrastructures for local businesses to keep going and to develop a new aspect to their business during this time. In the north of Italy, in Valsamoggia, the Municipalities in Transition team has been working alongside the municipality to create a platform to map all the local businesses who are offering a home delivery service. It is now being used by 72 businesses, and its model is being adopted by other places too. The article about the initiative closes with these words: “Whatever the future holds there is definitely a feeling of “We can do this!” in the face of uncertainty, hoping that this seed of resilience, continues to nurture the importance of community long after this “coronated” season.

Some people are not letting the lockdown stop them from planning new Transition activities. The newest Transition initiative in the US is Eco Vista, which is the name chosen by students at the University of California, Santa Barbara, to describe their vision of turning their 23,000-resident community of Isla Vista, consisting eighty percent of students, into a model eco-village by 2030 for other student communities to draw on and ultimately to create a network of such communities. Some of the group recently appeared in a webinar with Transition US to talk more about where the idea came from and how it’s going:

It has been fascinating to see how strategies and approaches trialled by the Transition movement for years are, during this crisis, being picked up and looked at afresh. The BBC, for example, wrote a long article about the potential role that local currencies could play in helping businesses during the crisis.

Community energy

We are also seeing a lot of projects that were begun by Transition groups coming to maturity and play an active role, both in supporting communities through COVID-19, and through modelling ‘bounce forward’ strategies. Community energy groups have, over the last 10 years, grown to a point where they now manage large amounts of renewable energy generation capacity. Ouse Valley Energy Services Company (OVESCO), which grew out of Transition Town Lewes, has been installing renewables through community investment since its first installment on a school in Nayland in 2011. It has done a huge amount to mentor surrounding communities to do that same. Now in the south east of the UK there are many community renewables projects, and many of those are contributing their dividends this year to community COVID-19 responses and food banks. When your model means you don’t have directors getting huge bonuses, those funds can go to things that mean more to the community.

In Portugal Transição São Luís, who have been involved in renewable energy projects since 2012, recently held a workshop together with Proseu (an EU renewables project) and the Science Department at the University of Lisbon called ‘Walks to a new energy model in San Luís. The workshop is held by the informal group ‘Energy with Joy’, and the proposal is to design concrete steps forward to their dream of making São Luis a ‘Solar Village’. They want to bulk buy solar photovoltaic systems, and in the longer term to set up a PV production facility in the village.

Bouncing Forward

While it is clear that the process of ‘bouncing forward’, of #BuildBackBetter, will not be easy, and indeed while many governments are already showing their commitment to #BuildBackWorse, bailing out fossil fuel companies and airlines among others, we already know much of what needs to happen now. Building a new food system that is more local and resilient is now both an economic strategy but also a survival strategy. Bold, bright, brilliant action now that sets out to start building a different future is vital. Transition groups continue to show what’s possible.

Community responses are always nuanced and context and place-specific in ways that top-down approaches can never be. They are able to understand and respond to a place, to its needs and opportunities in vitally-needed ways. They can build on surprising, sometimes chance relationships between people, businesses, institutions, places and ideas in a way that some central policy unit would never even begin to conceive.

Margaret Mead once famously said “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has”. That was never truer than it is today. Over those 13 years since the Transition movement started, I have visited many hundreds of Transition groups. I have never met anyone who told me that getting involved in being part of developing bottom-up community solutions had somehow impoverished their lives, made them more anxious, feel more isolated. The ability of these groups to create, hold and nurture ‘What If’ spaces where people can come together to imagine what ‘bouncing forward’ means in that context have been vital incubators of new ideas and fresh thinking.

And most of this has happened independent of government funding, meaningful support. Imagine how further along we might be if this work were properly resourced? Until now, one persistent cultural narrative in the Global North has been that there is “no such thing as society”, and that all resources should go into larger scale solutions. But this crisis has shown that of course there is such a thing as society. And in many cases it is society that has responded more effectively to this crisis than governments have. They need to be viewed as the cornerstone of ‘bouncing back’. This small selection of stories from the Transition movement show that this is where the seeds of a better future can be found.

(feature image by Nicholas Bartos on Unsplash)

Originally posted at Transition Network

Being a typical individualist, I haven't gone there, but the plan still makes sense:

TRANSITION TOWNS ADOPT FOUR KEY ASSUMPTIONS:

1 That life with dramatically lower energy consumption is inevitable; it's better to plan now than be taken by surprise.

2 That our communities presently lack the resilience to weather the severe energy shocks that will accompany peak oil and climate change.

3 That we have to act collectively and act now.

4 That by unleashing the collective intellect of those around us to creatively and proactively design our energy descent we can build ways of living that are more connected, more enriching and recognize the biological limits of our planet.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/home-property/67582964/how-to-live-in-a-transition-town

There's a particular type of human required to launch such schemes: team-builder. You could add community organiser, perhaps, but that model defers too much to the status quo. Pioneer ethos is requisite.

What do we imagine this COVID 19 is?. A cloud, vaporous and poisonous? A shadow that falls on the lungs of humans? A grinning mask that hides behind every person's face? A curse? A weapon? A static charge that jumps from person to person if they get too close? A ancient enemy that's broken through the crust of civilisation to claim its dues? A virus? What's a virus? Who, aside from those who study them deeply, knows that, and if there are such people, are they spinning out beyond the limits of "conventional" science the way the quantum physicists have, dipping into poetry and mysticism dictionaries in order to describe what they've found?

Turning our considerable ability to think and feel toward the Covid will change the way we see the world. In my opinion.

The word “Virus” translates as "toxin". Virology is highly theoretical given that viral genomes are modelled, not observed. Viral "particles" are not alive, which is why antibiotics don't work on them. We all know this , correct? But few people seem to know that viruses are PART of us. we have trillions of them in our biome and our immune systems are so complex that science does not fully understand them.

All that aside, a realistic picture may be formed based on the data. Anyone who cares to spend a little time and with basic schooling will naturally ask the right questions when presented with statistics. They do not correlate with the status "pandemic" in any possible way.

However, it is clear that questions of any type are not welcomed in our society. They are censored and dismissed, because critical thinking is not commonly practiced as most people are just trying to get through the day and put food on table

Before I dismiss you as ignorant, let me ask you a few simple questions:

I look forward to your informed and informative reply; feel free (!) to add a link to credible information to support your answers.

"Have you heard of gene/genome sequencing?"

Yes, but I don't know what it is at the physical rather than conceptual level. When Bob says our knowledge of them is modelled not observed, how do we observe the SARS-CoV-2 virus genome sequencing?

Bob might want to try answer that but in case he doesn’t oblige:

For example, isolate viral material from patient sample. Do Sanger sequencing. Obtain genome. Nothing “theoretical” or “modelled” about it, at least not in the sense that Bob seemed to imply.

I could say a lot more but I don’t want to pre-empt Bob’s answers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanger_sequencing

Let's leave Bob out of it for a moment. How do humans observe genome sequencing? It's not a trick question, I actually want to know.

might be better phrased as 'how do humans observe genomes?'

I don’t quite understand the question. The sequence of a genome is a long code written in/with four letters (A, T, G, and C). Just like a computer can read code, cells can read their DNA, and translate it into proteins. With the DNA code, there are certain start and stop signals, etc. Unlike proteins, the DNA sequence (code) is its function, in a simplified view; protein function depends on three-dimensional structure. You can also ‘observe’ the genome by looking at the products of its transcription called transcripts, e.g. mRNA (messenger RNA).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messenger_RNA

yes, but I'm not a cell, I'm a human and I want to know how other humans can observe the genome from the outside.

When you saying 'by looking at', how is that done in the physical world?

There are so many ways of ‘observing’ the genome.

One way, is looking at the proteins translated and expressed in a cell, cells, or tissue, as I said.

A more direct way, is looking at DNA expression, e.g. by measuring all transcripts in a cell or a sample of cells. One way of doing this is using micro-array chips. Wikipedia is good for basic information, e.g. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DNA_microarray [have a look at the very short and basic video on the RH side and the schematics on the RH side]

Like most things in modern (natural) science, physical measurements (which are really interactions with the physical world per se) need to be transformed into information that a human can take in and digest, mentally speaking. This is greatly aided by computers, as Lprent said.

We are a long way off Bob’s initial comment

Hi Weka, here's what I've gleaned from Google and Wikipedia – apologies if this is repeating what Incognito and others have already written.

All genomes are physically tiny (they have to pack into cells, or organelles, or viral envelopes, etc.), but not so tiny that they can't be observed using special microscopes and methods. Here's a link to the image of a circular bacterial (Escherichia coli) (double stranded DNA) genome caught part way through the act of replication, i.e. copying itself.

https://www.chegg.com/homework-help/figure-134b-shows-autoradiograph-replicating-bacterial-chrom-chapter-13-problem-3aeq-solution-9780077418687-exc

The smallest/shortest (viral) genomes, of the Circoviridae family (ssDNA), are <2000 nucelotides.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virus#Genome

Apart from observing genomes/chromosomes using various microscopy techniques, you can 'observe' a genome by sequencing it (Sanger sequencing, which Incognito has mentioned, is one common method; for genomes of any size Next Generation Sequencing methods are used, and yes, many DNA sequencing methods make use of fluorescent dyes/labels) and then reading the sequence of bases (A G T C).

Here's a link (to an entry in the NCBI database) for the sequence of one of the smallest genomes, that of the porcine circovirus 1:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AF071879.1

Like almost everything these days, you observe genome sequencing with computers.

There are a number of techniques ranging from causing fluorescently or dyed bases to ionic detection of the different bases.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DNA_sequencing#High-throughput_methods

so one way is to dye the material, and then how is it observed? eg how does the computer get its data?

(wiki is almost unfit for purpose now for science articles. Not a hope in hell that most people reading the first sentence in your link will understand it).

There is much scientific jargon in this 5 minute Illumina (Solexa) Youtube video describing their next generation sequencing (NGS) methodology.

That's unfortunate but largely unavoidable – simplification and analogy can help to get ideas across, but too much simplification carries its own risks. You can see from some of the comments on the video that already knowing something about DNA sequencing is no guarantee of complete understanding.

The Illumina sequencing workflow

While I was typing this, the next Youtube video (also ~5 minutes) started playing; it might be more helpful to anyone interested.

Next Generation Sequencing

I need a 3 or 4 paragraph (short) explanation. I'd be willing to watch a vid if I thought it was going to answer my question

Most first-year university students with a chemistry and molecular biology education to at least year 12 level would need more than 3 or 4 artfully-worded paragraphs to get the hang of NGS.

Like many multi-step scientific methods, it's all so simple once you understand it, but that payoff may not be worth investing 5 minutes of your time. For me there are certainly more topics that fall into that category than out of it.

I don't think I'm asking to get the hang of NGS though.

It will be more than 5 mins. It will be all the stops and rewinds to go over things again, having to look up words and so on. When I write posts based around videos, it's almost never a matter of watching through once.

This 3.5 minute video on Sanger sequencing is quite good.

"so one way is to dye the material, and then how is it observed? eg how does the computer get its data?"

It’s that type of question that these videos seek to answer. Because the 'how' of obtaining DNA sequence data via Sanger sequencing and NGS is technical in nature (involving specific technical steps that require some background knowledge of molecular biology and chemistry to truly understand), it's going to be a challenge to give a meaningful explanation in 3 or 4 paragraphs, let alone a video. I certainly wouldn't attempt it, but some have. Best of luck – Incognito provided this link @2.1.1.1.1.

It’d be impossible to look at molecular level DNA with a visible light. The frequency length was too long to resolve down to that size level. They used electron microscopes originally. But of course whatever they looked at would uncoil and disintegrate from the energy. Same with ultra violet and other shorter frequency radiation.

With florescence or with dyed, you’d have a sensor that looks for a particular frequency of light. Often not visible in a frequency that humans could see – but which machines can detect. For ionic, you’d typically be using a sensor that measures a electrical field, or passes a electrical field through a molecule and looks for differences in resistance.

They’d figured out what the possible molecules were earlier by sequestering DNA and RNA and then breaking the bods between molecules and separating then. Probably using a molecular weight separation or electrophoresis.

The hard bit with looking at DNA or RNA is to get the sequence of the molecules. They do that via a variety of methods – but ultimately the mostly run them through restricted gateway that lets one molecule of a strange of DNA or RNA through at a time – then they just have to identify which of the 4 possible molecules it is.

The sequence of molecules of a stretch of DNA/RNA (typically surrounded by check or cut molecules) codes for a particular protein when it is transcribed.

After that I’d have to start thinking – so I’ll get back to work again.

ta, that seems to be getting closer to a description I can get my head around.