Green growth or degrowth?

Green growth or degrowth?

Written By:

notices and features - Date published:

11:07 am, November 22nd, 2023 - 21 comments

Categories: climate change, economy -

Tags: agrowth, degrowth, green growth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Ivan Savin, ESCP Business School and Lewis King, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Idea of green growth losing traction among climate policy researchers, survey of nearly 800 academics reveals

When she took to the floor to give her State of the Union speech on 13 September, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen largely stood by the script. Describing her vision of an economically buoyant and sustainable Europe in the era of climate change, she called on the EU to accelerate the development of the clean-tech sector, “from wind to steel, from batteries to electric vehicles”. “When it comes to the European Green Deal, we stick to our growth strategy,” von der Leyen said.

Her plans were hardly idiosyncratic. The notion of green growth – the idea that environmental goals can be aligned with continued economic growth – is still the common economic orthodoxy for major institutions like the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The OECD has promised to “strengthen their efforts to pursue green growth strategies […], acknowledging that green and growth can go hand-in-hand”, while the World Bank has called for “inclusive green growth” where “greening growth is necessary, efficient, and affordable”. Meanwhile, the EU has framed green growth as

“a basis to sustain employment levels and secure the resources needed to increase public welfare […] transforming production and consumption in ways that reconcile increasing GDP with environmental limits”.

However, our survey of nearly 800 climate policy researchers from around the world reveals widespread scepticism toward the concept in high-income countries, amid mounting literature arguing that the principle may neither be viable nor desirable. Instead, alternative post-growth paradigms including “degrowth” and “agrowth” are gaining traction.

Differentiating green growth from agrowth and degrowth

But what do these terms signify?

The “degrowth” school of thought proposes a planned reduction in material consumption in affluent nations to achieve more sustainable and equitable societies. Meanwhile, supporters of “agrowth” adopt a neutral view of economic growth, focusing on achieving sustainability irrespective of GDP fluctuations. Essentially, both positions represent scepticism toward the predominant “green growth” paradigm with degrowth representing a more critical view.

Much of the debate centres around the concept of decoupling – whether the economy can grow without corresponding increases in environmental degradation or greenhouse gas emissions. Essentially, it signifies a separation of the historical linkage between GDP growth and its adverse environmental effects. Importantly, absolute decoupling rather than relative decoupling is necessary for green growth to succeed. In other words, emissions should decrease during economic growth, and not just grow more slowly.

Green growth proponents assert that absolute decoupling is achievable in the long term, although there is a division regarding whether there will be a short-term hit to economic growth. The degrowth perspective is critical that absolute decoupling is feasible at the global scale and can be achieved at the rapid rate required to stay within Paris climate targets. A recent study found that current rates of decoupling in high-income are falling far short of what is needed to limit global heating to well below 2°C as set out by the Paris Agreement.

The agrowth position covers more mixed, middle-ground views on the decoupling debate. Some argue that decoupling is potentially plausible under the right policies, however, the focus should be on policies rather than targets as this is confusing means and ends. Others may argue that the debate is largely irrelevant as GDP is a poor indicator of societal progress – a “GDP paradox” exists, where the indicator continues to be dominant in economics and politics despite its widely recognised failings.

7 out of 10 climate experts sceptical of green growth

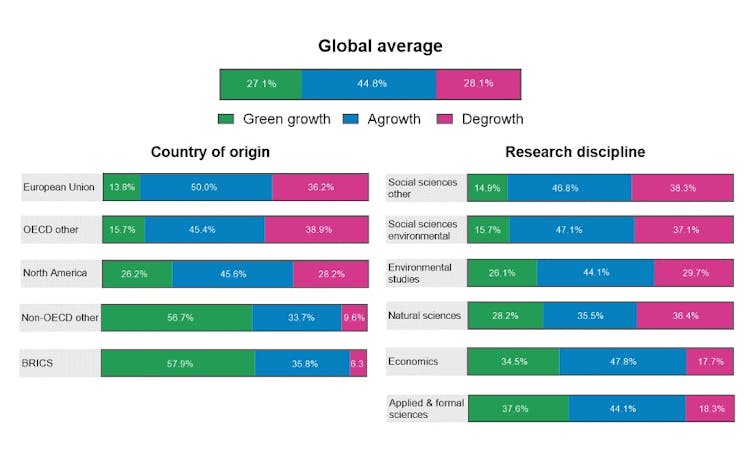

How prevalent are degrowth and agrowth views among experts? As part of a recent survey completed by 789 global researchers who have published on climate change mitigation policies, we asked questions to assess the respondents’ positions on the growth debate. Strikingly, 73% of all respondents expressed views aligned with “agrowth” or “degrowth” positions, with the former being the most popular. We found that the opinions varied based on the respondent’s country and discipline (see the figure below).

Fourni par l’auteur

While the OECD itself strongly advocates for green growth, researchers from the EU and other OECD nations demonstrated high levels of scepticism. In contrast, over half of the researchers from non-OECD nations, especially in emerging economies like the BRICS nations, were more supportive of green growth.

Disciplinary rifts

Furthermore, a disciplinary divide exists. Environmental and other social scientists, excluding orthodox economists, were the most sceptical of green growth. In contrast, economists and engineers showed the highest preference for green growth, possibly indicative of trust in technological progress and conventional economic models that suggest economic growth and climate goals are compatible.

Our analysis also examined the link between the growth positions and the GDP per capita of a respondent’s country of origin. A discernible trend emerged: as national income rises, there is increased scepticism toward green growth. At higher income levels, experts increasingly supported the post-growth argument that beyond a point, the socio-environmental costs of growth may outweigh the benefits.

The results were even more pronounced when we factored in the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI), suggesting that aspects beyond income, such as inequality and overall development, might influence these views.

In a world grappling with climate change and socio-economic disparities, these findings should not simply be dismissed. They underline the need for a more holistic dialogue on sustainable development, extending beyond the conventional green growth paradigm.

Post-growth thought no longer a fringe position

Although von der Leyen firmly stood in the green growth camp, this academic shift is increasingly reflected in the political debate. In May 2023, the European Parliament hosted a conference on the topic of “Beyond Growth” as an initiative of 20 MEPs from five different political groups and supported by over 50 partner organisations. Its main objective was to discuss policy proposals to move beyond the approach of national GDP growth being the primary measure of success.

Six national and regional governments – Scotland, New Zealand, Iceland, Wales, Finland, and Canada – have joined the Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEGo) partnership. The primary aim of the movement is to transition to “an economy designed to serve people and planet, not the other way around.”

Clearly, post-growth thought is no longer a fringe, radical position within those working on solutions to climate change. Greater attention needs to be given to why some experts are doubtful that green growth can be achieved as well as potential alternatives focussed on wider concepts of societal wellbeing rather than limited thinking in terms of GDP growth.![]()

Ivan Savin, Associate professor of business analytics, research fellow at ICTA-UAB, ESCP Business School and Lewis King, Postdoctoral research fellow in Ecological economics, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Posts

21 comments on “Green growth or degrowth? ”

- Comments are now closed

- Comments are now closed

Recent Comments

- Anne on

- Barfly on

- Visubversa to tWig on

- Michael Scott to tc on

- Anne on

- tWig on

- tWig on

- Michael Scott to Michael Scott on

- tc on

- Subliminal on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Reality on

- PsyclingLeft.Always to georgecom on

- SPC on

- SPC on

- Rodel to tsmithfield on

- SPC on

- georgecom to tsmithfield on

- PsyclingLeft.Always to joe90 on

- joe90 to PsyclingLeft.Always on

- Reality on

- PsyclingLeft.Always to joe90 on

- joe90 on

- joe90 on

- SPC to tsmithfield on

- Res Publica to ghostwhowalksnz on

- tsmithfield to JeremyB on

- Kay to tsmithfield on

- mpledger to tsmithfield on

- Reality on

- adam on

- Ad on

- joe90 on

- tsmithfield on

- tsmithfield to Barfly on

- I Feel Love to tsmithfield on

- Barfly to tsmithfield on

Recent Posts

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Guest post

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by lprent

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by weka

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by lprent

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by lprent

-

by Guest post

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

- Stories of varying weight

More Than A FeildingBy David Slack5 hours ago

- Balancing External Security and the Economy

New Zealand is again having to reconcile conflicting pressures from its military and its trade interests. Should we join Pillar Two of AUKUS and risk compromising our markets in China? For a century after New Zealand was founded in 1840, its external security arrangements and external economics arrangements were aligned. ...PunditBy Brian Easton18 hours ago

New Zealand is again having to reconcile conflicting pressures from its military and its trade interests. Should we join Pillar Two of AUKUS and risk compromising our markets in China? For a century after New Zealand was founded in 1840, its external security arrangements and external economics arrangements were aligned. ...PunditBy Brian Easton18 hours ago - Weekly Climate Wrap: The unravelling of the offsets

The KakaBy Bernard Hickey23 hours ago

- What makes us tick

This morning the sky was bright.The birds, in their usual joyous bliss. Nature doesn’t seem to feel the heat of what might angst humans.Their calls are clear and beautiful.Just some random thoughts:MāoriPaul Goldsmith has announced his government will roll back the judiciary’s rulings on Māori Customary Marine Title, which recognises ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui24 hours ago

This morning the sky was bright.The birds, in their usual joyous bliss. Nature doesn’t seem to feel the heat of what might angst humans.Their calls are clear and beautiful.Just some random thoughts:MāoriPaul Goldsmith has announced his government will roll back the judiciary’s rulings on Māori Customary Marine Title, which recognises ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui24 hours ago - Foreshore and seabed 2.0

In 2003, the Court of Appeal delivered its decision in Ngati Apa v Attorney-General, ruling that Māori customary title over the foreshore and seabed had not been universally extinguished, and that the Māori Land Court could determine claims and confirm title if the facts supported it. This kicked off the ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 day ago

In 2003, the Court of Appeal delivered its decision in Ngati Apa v Attorney-General, ruling that Māori customary title over the foreshore and seabed had not been universally extinguished, and that the Māori Land Court could determine claims and confirm title if the facts supported it. This kicked off the ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 day ago - Gordon Campbell on the Royal Commission report into abuse in care

Earlier this week at Parliament, Labour leader Chris Hipkins was applauded for saying that the response to the final report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care had to be “bigger than politics.” True, but the fine words, apologies and “we hear you” messages will soon ring ...WerewolfBy lyndon1 day ago

Earlier this week at Parliament, Labour leader Chris Hipkins was applauded for saying that the response to the final report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care had to be “bigger than politics.” True, but the fine words, apologies and “we hear you” messages will soon ring ...WerewolfBy lyndon1 day ago - The Kākā’s Pick 'n' Mix for Friday, July 26

TL;DR: In news breaking this morning:The Ministry of Education is cutting $2 billion from its school building programme so the National-ACT-NZ First Coalition Government has enough money to deliver tax cuts; The Government has quietly lowered its child poverty reduction targets to make them easier to achieve;Te Whatu Ora-Health NZ’s ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago

TL;DR: In news breaking this morning:The Ministry of Education is cutting $2 billion from its school building programme so the National-ACT-NZ First Coalition Government has enough money to deliver tax cuts; The Government has quietly lowered its child poverty reduction targets to make them easier to achieve;Te Whatu Ora-Health NZ’s ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago - Weekly Roundup 26-July-2024

Kia ora. These are some stories that caught our eye this week – as always, feel free to share yours in the comments. Our header image this week (via Eke Panuku) shows the planned upgrade for the Karanga Plaza Tidal Swimming Steps. The week in Greater Auckland On ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland1 day ago

Kia ora. These are some stories that caught our eye this week – as always, feel free to share yours in the comments. Our header image this week (via Eke Panuku) shows the planned upgrade for the Karanga Plaza Tidal Swimming Steps. The week in Greater Auckland On ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland1 day ago - God what a relief

More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 day ago

- Trust In Me

Trust in me in all you doHave the faith I have in youLove will see us through, if only you trust in meWhy don't you, you trust me?In a week that saw the release of the 3,000 page Abuse in Care report Christopher Luxon was being asked about Boot Camps. ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 day ago

Trust in me in all you doHave the faith I have in youLove will see us through, if only you trust in meWhy don't you, you trust me?In a week that saw the release of the 3,000 page Abuse in Care report Christopher Luxon was being asked about Boot Camps. ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 day ago - The Hoon around the week to July 26

TL;DR: The podcast above of the weekly ‘hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers last night features co-hosts and talking about the Royal Commission Inquiry into Abuse in Care report released this week, and with:The Kākā’s climate correspondent on a UN push to not recognise carbon offset markets and ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago

- The Kākā’s Journal of Record for Friday, July 26

TL;DR: As of 6:00 am on Friday, July 26, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:Transport: Simeon Brown announced $802.9 million in funding for 18 new trains on the Wairarapa and Manawatū rail lines, which ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago

TL;DR: As of 6:00 am on Friday, July 26, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:Transport: Simeon Brown announced $802.9 million in funding for 18 new trains on the Wairarapa and Manawatū rail lines, which ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago - Radical law changes needed to build road

The northern expressway extension from Warkworth to Whangarei is likely to require radical changes to legislation if it is going to be built within the foreseeable future. The Government’s powers to purchase land, the planning process and current restrictions on road tolling are all going to need to be changed ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 day ago

The northern expressway extension from Warkworth to Whangarei is likely to require radical changes to legislation if it is going to be built within the foreseeable future. The Government’s powers to purchase land, the planning process and current restrictions on road tolling are all going to need to be changed ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 day ago - Skeptical Science New Research for Week #30 2024

Open access notables Could an extremely cold central European winter such as 1963 happen again despite climate change?, Sippel et al., Weather and Climate Dynamics: Here, we first show based on multiple attribution methods that a winter of similar circulation conditions to 1963 would still lead to an extreme seasonal ...2 days ago

Open access notables Could an extremely cold central European winter such as 1963 happen again despite climate change?, Sippel et al., Weather and Climate Dynamics: Here, we first show based on multiple attribution methods that a winter of similar circulation conditions to 1963 would still lead to an extreme seasonal ...2 days ago - First they came for the Māori

Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui2 days ago

- Join us for the weekly Hoon on YouTube Live

Photo by Joshua J. Cotten on UnsplashWe’re back again after our mid-winter break. We’re still with the ‘new’ day of the week (Thursday rather than Friday) when we have our ‘hoon’ webinar with paying subscribers to The Kākā for an hour at 5 pm.Jump on this link on YouTube Livestream ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

Photo by Joshua J. Cotten on UnsplashWe’re back again after our mid-winter break. We’re still with the ‘new’ day of the week (Thursday rather than Friday) when we have our ‘hoon’ webinar with paying subscribers to The Kākā for an hour at 5 pm.Jump on this link on YouTube Livestream ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - Will the real PM Luxon please stand up?

Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui2 days ago

- Will debt reduction trump abuse in care redress?

Luxon speaks in Parliament yesterday about the Abuse in Care report. Photo: Hagen Hopkins/Getty ImagesTL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy today are:PM Christopher Luxon said yesterday in tabling the Abuse in Care report in Parliament he wanted to ‘do the ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

Luxon speaks in Parliament yesterday about the Abuse in Care report. Photo: Hagen Hopkins/Getty ImagesTL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy today are:PM Christopher Luxon said yesterday in tabling the Abuse in Care report in Parliament he wanted to ‘do the ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - Olywhites and Time Bandits

About a decade ago I worked with a bloke called Steve. He was the grizzled veteran coder, a few years older than me, who knew where the bodies were buried - code wise. Despite his best efforts to be approachable and friendly he could be kind of gruff, through to ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago

About a decade ago I worked with a bloke called Steve. He was the grizzled veteran coder, a few years older than me, who knew where the bodies were buried - code wise. Despite his best efforts to be approachable and friendly he could be kind of gruff, through to ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago - Why were the 1930s so hot in North America?

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Jeff Masters and Bob Henson Those who’ve trawled social media during heat waves have likely encountered a tidbit frequently used to brush aside human-caused climate change: Many U.S. states and cities had their single hottest temperature on record during the 1930s, setting incredible heat marks ...2 days ago

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Jeff Masters and Bob Henson Those who’ve trawled social media during heat waves have likely encountered a tidbit frequently used to brush aside human-caused climate change: Many U.S. states and cities had their single hottest temperature on record during the 1930s, setting incredible heat marks ...2 days ago - Throwback Thursday – Thinking about Expressways

Some of the recent announcements from the government have reminded us of posts we’ve written in the past. Here’s one from early 2020. There were plenty of reactions to the government’s infrastructure announcement a few weeks ago which saw them fund a bunch of big roading projects. One of ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland2 days ago

Some of the recent announcements from the government have reminded us of posts we’ve written in the past. Here’s one from early 2020. There were plenty of reactions to the government’s infrastructure announcement a few weeks ago which saw them fund a bunch of big roading projects. One of ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland2 days ago - The Kākā’s Pick 'n' Mix for Thursday, July 25

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 7:00 am on Thursday, July 25 are:News: Why Electric Kiwi is closing to new customers - and why it matters RNZ’s Susan EdmundsScoop: Government drops ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 7:00 am on Thursday, July 25 are:News: Why Electric Kiwi is closing to new customers - and why it matters RNZ’s Susan EdmundsScoop: Government drops ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - The Possum: Demon or Friend?

Hi,I felt a small wet tongue snaking through one of the holes in my Crocs. It explored my big toe, darting down one side, then the other. “He’s looking for some toe cheese,” said the woman next to me, words that still haunt me to this day.Growing up in New ...David FarrierBy David Farrier2 days ago

Hi,I felt a small wet tongue snaking through one of the holes in my Crocs. It explored my big toe, darting down one side, then the other. “He’s looking for some toe cheese,” said the woman next to me, words that still haunt me to this day.Growing up in New ...David FarrierBy David Farrier2 days ago - Not a story

Yesterday I happily quoted the Prime Minister without fact-checking him and sure enough, it turns out his numbers were all to hell. It’s not four kg of Royal Commission report, it’s fourteen.My friend and one-time colleague-in-comms Hazel Phillips gently alerted me to my error almost as soon as I’d hit ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago

Yesterday I happily quoted the Prime Minister without fact-checking him and sure enough, it turns out his numbers were all to hell. It’s not four kg of Royal Commission report, it’s fourteen.My friend and one-time colleague-in-comms Hazel Phillips gently alerted me to my error almost as soon as I’d hit ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago - The Kākā’s Journal of Record for Thursday, July 25

TL;DR: As of 6:00 am on Thursday, July 25, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day were:The Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry published its final report yesterday.PM Christopher Luxon and The Minister responsible for ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

TL;DR: As of 6:00 am on Thursday, July 25, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day were:The Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry published its final report yesterday.PM Christopher Luxon and The Minister responsible for ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - A tougher line on “proactive release”?

The Official Information Act has always been a battle between requesters seeking information, and governments seeking to control it. Information is power, so Ministers and government agencies want to manage what is released and when, for their own convenience, and legality and democracy be damned. Their most recent tactic for ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago

The Official Information Act has always been a battle between requesters seeking information, and governments seeking to control it. Information is power, so Ministers and government agencies want to manage what is released and when, for their own convenience, and legality and democracy be damned. Their most recent tactic for ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago - 'Let's build a motorway costing $100 million per km, before emissions costs'

TL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy today are:Transport and Energy Minister Simeon Brown is accelerating plans to spend at least $10 billion through Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) to extend State Highway One as a four-lane ‘Expressway’ from Warkworth to Whangarei ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago

TL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy today are:Transport and Energy Minister Simeon Brown is accelerating plans to spend at least $10 billion through Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) to extend State Highway One as a four-lane ‘Expressway’ from Warkworth to Whangarei ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago - Lester's Prescription – Positive Bleeding.

I live my life (woo-ooh-ooh)With no control in my destinyYea-yeah, yea-yeah (woo-ooh-ooh)I can bleed when I want to bleedSo come on, come on (woo-ooh-ooh)You can bleed when you want to bleedYea-yeah, come on (woo-ooh-ooh)Everybody bleed when they want to bleedCome on and bleedGovernments face tough challenges. Selling unpopular decisions to ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago

I live my life (woo-ooh-ooh)With no control in my destinyYea-yeah, yea-yeah (woo-ooh-ooh)I can bleed when I want to bleedSo come on, come on (woo-ooh-ooh)You can bleed when you want to bleedYea-yeah, come on (woo-ooh-ooh)Everybody bleed when they want to bleedCome on and bleedGovernments face tough challenges. Selling unpopular decisions to ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago - Casey Costello gaslights Labour in the House

Please note:To skip directly to the- parliamentary footage in the video, scroll to 1:21 To skip to audio please click on the headphone icon on the left hand side of the screenThis video / audio section is under development. ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui3 days ago

- Why is the Texas grid in such bad shape?

This is a re-post from the Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler Headline from 2021 The Texas grid, run by ERCOT, has had a rough few years. In 2021, winter storm Uri blacked out much of the state for several days. About a week ago, Hurricane Beryl knocked out ...3 days ago

This is a re-post from the Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler Headline from 2021 The Texas grid, run by ERCOT, has had a rough few years. In 2021, winter storm Uri blacked out much of the state for several days. About a week ago, Hurricane Beryl knocked out ...3 days ago - Gordon Campbell on a textbook case of spending waste by the Luxon government

Given the crackdown on wasteful government spending, it behooves me to point to a high profile example of spending by the Luxon government that looks like a big, fat waste of time and money. I’m talking about the deployment of NZDF personnel to support the US-led coalition in the Red ...WerewolfBy lyndon3 days ago

Given the crackdown on wasteful government spending, it behooves me to point to a high profile example of spending by the Luxon government that looks like a big, fat waste of time and money. I’m talking about the deployment of NZDF personnel to support the US-led coalition in the Red ...WerewolfBy lyndon3 days ago - The Kākā’s Pick 'n' Mix for Wednesday, July 24

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 7:40 am on Wednesday, July 24 are:Deep Dive: Chipping away at the housing crisis, including my comments RNZ/Newsroom’s The DetailNews: Government softens on asset sales, ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 7:40 am on Wednesday, July 24 are:Deep Dive: Chipping away at the housing crisis, including my comments RNZ/Newsroom’s The DetailNews: Government softens on asset sales, ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago - LXR Takaanini

As I reported about the city centre, Auckland’s rail network is also going through a difficult and disruptive period which is rapidly approaching a culmination, this will result in a significant upgrade to the whole network. Hallelujah. Also like the city centre this is an upgrade predicated on the City ...Greater AucklandBy Patrick Reynolds3 days ago

As I reported about the city centre, Auckland’s rail network is also going through a difficult and disruptive period which is rapidly approaching a culmination, this will result in a significant upgrade to the whole network. Hallelujah. Also like the city centre this is an upgrade predicated on the City ...Greater AucklandBy Patrick Reynolds3 days ago - Four kilograms of pain

Today, a 4 kilogram report will be delivered to Parliament. We know this is what the report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in State and Faith-based Care weighs, because our Prime Minister told us so.Some reporter had blindsided him by asking a question about something done by ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago

Today, a 4 kilogram report will be delivered to Parliament. We know this is what the report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in State and Faith-based Care weighs, because our Prime Minister told us so.Some reporter had blindsided him by asking a question about something done by ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago - The Kākā’s Journal of Record for Wednesday, July 24

TL;DR: As of 7:00 am on Wednesday, July 24, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:Beehive: Transport Minister Simeon Brown announced plans to use PPPs to fund, build and run a four-lane expressway between Auckland ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago

TL;DR: As of 7:00 am on Wednesday, July 24, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:Beehive: Transport Minister Simeon Brown announced plans to use PPPs to fund, build and run a four-lane expressway between Auckland ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago - Luxon gets caught out

NewstalkZB host Mike Hosking, who can usually be relied on to give Prime Minister Christopher Luxon an easy run, did not do so yesterday when he interviewed him about the HealthNZ deficit. Luxon is trying to use a deficit reported last year by HealthNZ as yet another example of the ...PolitikBy Richard Harman3 days ago

NewstalkZB host Mike Hosking, who can usually be relied on to give Prime Minister Christopher Luxon an easy run, did not do so yesterday when he interviewed him about the HealthNZ deficit. Luxon is trying to use a deficit reported last year by HealthNZ as yet another example of the ...PolitikBy Richard Harman3 days ago - A worrying sign

Back in January a StatsNZ employee gave a speech at Rātana on behalf of tangata whenua in which he insulted and criticised the government. The speech clearly violated the principle of a neutral public service, and StatsNZ started an investigation. Part of that was getting an external consultant to examine ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant4 days ago

Back in January a StatsNZ employee gave a speech at Rātana on behalf of tangata whenua in which he insulted and criticised the government. The speech clearly violated the principle of a neutral public service, and StatsNZ started an investigation. Part of that was getting an external consultant to examine ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant4 days ago - Are we fine with 47.9% home-ownership by 2048?

Renting for life: Shared ownership initiatives are unlikely to slow the slide in home ownership by much. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāTL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy today are:A Deloitte report for Westpac has projected Aotearoa’s home-ownership rate will ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

Renting for life: Shared ownership initiatives are unlikely to slow the slide in home ownership by much. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāTL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy today are:A Deloitte report for Westpac has projected Aotearoa’s home-ownership rate will ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - Let's Win This

You're broken down and tiredOf living life on a merry go roundAnd you can't find the fighterBut I see it in you so we gonna walk it outAnd move mountainsWe gonna walk it outAnd move mountainsAnd I'll rise upI'll rise like the dayI'll rise upI'll rise unafraidI'll rise upAnd I'll ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago

You're broken down and tiredOf living life on a merry go roundAnd you can't find the fighterBut I see it in you so we gonna walk it outAnd move mountainsWe gonna walk it outAnd move mountainsAnd I'll rise upI'll rise like the dayI'll rise upI'll rise unafraidI'll rise upAnd I'll ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago - Waimahara: The Singing Spirit of Water

There’s been a change in Myers Park. Down the steps from St. Kevin’s Arcade, past the grassy slopes, the children’s playground, the benches and that goat statue, there has been a transformation. The underpass for Mayoral Drive has gone from a barren, grey, concrete tunnel, to a place that thrums ...Greater AucklandBy Connor Sharp4 days ago

There’s been a change in Myers Park. Down the steps from St. Kevin’s Arcade, past the grassy slopes, the children’s playground, the benches and that goat statue, there has been a transformation. The underpass for Mayoral Drive has gone from a barren, grey, concrete tunnel, to a place that thrums ...Greater AucklandBy Connor Sharp4 days ago - A major milestone: Global climate pollution may have just peaked

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections Global society may have finally slammed on the brakes for climate-warming pollution released by human fossil fuel combustion. According to the Carbon Monitor Project, the total global climate pollution released between February and May 2024 declined slightly from the amount released during the same ...4 days ago

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections Global society may have finally slammed on the brakes for climate-warming pollution released by human fossil fuel combustion. According to the Carbon Monitor Project, the total global climate pollution released between February and May 2024 declined slightly from the amount released during the same ...4 days ago - The Kākā’s Pick 'n' Mix for Tuesday, July 23

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 7:00 am on Tuesday, July 23 are:Deep Dive: Penlink: where tolling rhetoric meets reality BusinessDesk-$$$’s Oliver LewisScoop: Te Pūkenga plans for regional polytechs leak out ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 7:00 am on Tuesday, July 23 are:Deep Dive: Penlink: where tolling rhetoric meets reality BusinessDesk-$$$’s Oliver LewisScoop: Te Pūkenga plans for regional polytechs leak out ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - The Kākā’s Journal of Record for Tuesday, July 23

TL;DR: As of 6:00 am on Tuesday, July 23, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:Health: Shane Reti announced the Board of Te Whatu Ora- Health New Zealand was being replaced with Commissioner Lester Levy ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

TL;DR: As of 6:00 am on Tuesday, July 23, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:Health: Shane Reti announced the Board of Te Whatu Ora- Health New Zealand was being replaced with Commissioner Lester Levy ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - HealthNZ and Luxon at cross purposes over budget blowout

Health NZ warned the Government at the end of March that it was running over Budget. But the reasons it gave were very different to those offered by the Prime Minister yesterday. Prime Minister Christopher Luxon blamed the “botched merger” of the 20 District Health Boards (DHBs) to create Health ...PolitikBy Richard Harman4 days ago

Health NZ warned the Government at the end of March that it was running over Budget. But the reasons it gave were very different to those offered by the Prime Minister yesterday. Prime Minister Christopher Luxon blamed the “botched merger” of the 20 District Health Boards (DHBs) to create Health ...PolitikBy Richard Harman4 days ago - 2500-3000 more healthcare staff expected to be fired, as Shane Reti blames Labour for a budget defic...

Long ReadKey Summary: Although National increased the health budget by $1.4 billion in May, they used an old funding model to project health system costs, and never bothered to update their pre-election numbers. They were told during the Health Select Committees earlier in the year their budget amount was deficient, ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui4 days ago

Long ReadKey Summary: Although National increased the health budget by $1.4 billion in May, they used an old funding model to project health system costs, and never bothered to update their pre-election numbers. They were told during the Health Select Committees earlier in the year their budget amount was deficient, ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui4 days ago - Might Kamala Harris be about to get a 'stardust' moment like Jacinda Ardern?

As a momentous, historic weekend in US politics unfolded, analysts and commentators grasped for precedents and comparisons to help explain the significance and power of the choice Joe Biden had made. The 46th president had swept the Democratic party’s primaries but just over 100 days from the election had chosen ...PunditBy Tim Watkin5 days ago

As a momentous, historic weekend in US politics unfolded, analysts and commentators grasped for precedents and comparisons to help explain the significance and power of the choice Joe Biden had made. The 46th president had swept the Democratic party’s primaries but just over 100 days from the election had chosen ...PunditBy Tim Watkin5 days ago - Solutions Interview: Steven Hail on MMT & ecological economics

TL;DR: I’m casting around for new ideas and ways of thinking about Aotearoa’s political economy to find a few solutions to our cascading and self-reinforcing housing, poverty and climate crises.Associate Professor runs an online masters degree in the economics of sustainability at Torrens University in Australia and is organising ...The KakaBy Steven Hail5 days ago

- Reported back

The Finance and Expenditure Committee has reported back on National's Local Government (Water Services Preliminary Arrangements) Bill. The bill sets up water for privatisation, and was introduced under urgency, then rammed through select committee with no time even for local councils to make a proper submission. Naturally, national's select committee ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant5 days ago

The Finance and Expenditure Committee has reported back on National's Local Government (Water Services Preliminary Arrangements) Bill. The bill sets up water for privatisation, and was introduced under urgency, then rammed through select committee with no time even for local councils to make a proper submission. Naturally, national's select committee ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant5 days ago - Vandrad the Viking, Christopher Coombes, and Literary Archaeology

Some years ago, I bought a book at Dunedin’s Regent Booksale for $1.50. As one does. Vandrad the Viking (1898), by J. Storer Clouston, is an obscure book these days – I cannot find a proper online review – but soon it was sitting on my shelf, gathering dust alongside ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2215 days ago

Some years ago, I bought a book at Dunedin’s Regent Booksale for $1.50. As one does. Vandrad the Viking (1898), by J. Storer Clouston, is an obscure book these days – I cannot find a proper online review – but soon it was sitting on my shelf, gathering dust alongside ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2215 days ago - Gordon Campbell On The Biden Withdrawal

History is not on the side of the centre-left, when Democratic presidents fall behind in the polls and choose not to run for re-election. On both previous occasions in the past 75 years (Harry Truman in 1952, Lyndon Johnson in 1968) the Democrats proceeded to then lose the White House ...WerewolfBy lyndon5 days ago

History is not on the side of the centre-left, when Democratic presidents fall behind in the polls and choose not to run for re-election. On both previous occasions in the past 75 years (Harry Truman in 1952, Lyndon Johnson in 1968) the Democrats proceeded to then lose the White House ...WerewolfBy lyndon5 days ago - Joe Biden's withdrawal puts the spotlight back on Kamala and the USA's complicated relatio...

This is a free articleCoverageThis morning, US President Joe Biden announced his withdrawal from the Presidential race. And that is genuinely newsworthy. Thanks for your service, President Biden, and all the best to you and yours.However, the media in New Zealand, particularly the 1News nightly bulletin, has been breathlessly covering ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui5 days ago

This is a free articleCoverageThis morning, US President Joe Biden announced his withdrawal from the Presidential race. And that is genuinely newsworthy. Thanks for your service, President Biden, and all the best to you and yours.However, the media in New Zealand, particularly the 1News nightly bulletin, has been breathlessly covering ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui5 days ago - Why we have to challenge our national fiscal assumptions

A homeless person’s camp beside a blocked-off slipped damage walkway in Freeman’s Bay: we are chasing our tail on our worsening and inter-related housing, poverty and climate crises. Photo: Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāTL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

A homeless person’s camp beside a blocked-off slipped damage walkway in Freeman’s Bay: we are chasing our tail on our worsening and inter-related housing, poverty and climate crises. Photo: Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāTL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - Existential Crisis and Damaged Brains

What has happened to it all?Crazy, some'd sayWhere is the life that I recognise?(Gone away)But I won't cry for yesterdayThere's an ordinary worldSomehow I have to findAnd as I try to make my wayTo the ordinary worldYesterday morning began as many others - what to write about today? I began ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago

What has happened to it all?Crazy, some'd sayWhere is the life that I recognise?(Gone away)But I won't cry for yesterdayThere's an ordinary worldSomehow I have to findAnd as I try to make my wayTo the ordinary worldYesterday morning began as many others - what to write about today? I began ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago - A speed limit is not a target, and yet…

This is a guest post from longtime supporter Mr Plod, whose previous contributions include a proposal that Hamilton become New Zealand’s capital city, and that we should switch which side of the road we drive on. A recent Newsroom article, “Back to school for the Govt’s new speed limit policy“, ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post5 days ago

This is a guest post from longtime supporter Mr Plod, whose previous contributions include a proposal that Hamilton become New Zealand’s capital city, and that we should switch which side of the road we drive on. A recent Newsroom article, “Back to school for the Govt’s new speed limit policy“, ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post5 days ago - The Kākā’s Pick 'n' Mix for Monday, July 22

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 7:00 am on Monday, July 22 are:Today’s Must Read: Father and son live in a tent, and have done for four years, in a million ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 7:00 am on Monday, July 22 are:Today’s Must Read: Father and son live in a tent, and have done for four years, in a million ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - The Kākā’s Journal of Record for Monday, July 22

TL;DR: As of 7:00 am on Monday, July 22, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:US President Joe Biden announced via X this morning he would not stand for a second term.Multinational professional services firm ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

TL;DR: As of 7:00 am on Monday, July 22, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:US President Joe Biden announced via X this morning he would not stand for a second term.Multinational professional services firm ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - 2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #29

A listing of 32 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, July 14, 2024 thru Sat, July 20, 2024. Story of the week As reflected by preponderance of coverage, our Story of the Week is Project 2025. Until now traveling ...6 days ago

A listing of 32 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, July 14, 2024 thru Sat, July 20, 2024. Story of the week As reflected by preponderance of coverage, our Story of the Week is Project 2025. Until now traveling ...6 days ago - I'd like to share what I did this weekend

Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui6 days ago

- For the children – Why mere sentiment can be a misleading force in our lives, and lead to unex...

National: The Party of ‘Law and Order’ IntroductionThis weekend, the Government formally kicked off one of their flagship policy programs: a military style boot camp that New Zealand has experimented with over the past 50 years. Cartoon credit: Guy BodyIt’s very popular with the National Party’s Law and Order image, ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui6 days ago

National: The Party of ‘Law and Order’ IntroductionThis weekend, the Government formally kicked off one of their flagship policy programs: a military style boot camp that New Zealand has experimented with over the past 50 years. Cartoon credit: Guy BodyIt’s very popular with the National Party’s Law and Order image, ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui6 days ago - A friend in uncertain times

Day one of the solo leg of my long journey home begins with my favourite sound: footfalls in an empty street. 5.00 am and it’s already light and already too warm, almost.If I can make the train that leaves Budapest later this hour I could be in Belgrade by nightfall; ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack6 days ago

Day one of the solo leg of my long journey home begins with my favourite sound: footfalls in an empty street. 5.00 am and it’s already light and already too warm, almost.If I can make the train that leaves Budapest later this hour I could be in Belgrade by nightfall; ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack6 days ago - The Chaotic World of Male Diet Influencers

Hi,We’ll get to the horrific world of male diet influencers (AKA Beefy Boys) shortly, but first you will be glad to know that since I sent out the Webworm explaining why the assassination attempt on Donald Trump was not a false flag operation, I’ve heard from a load of people ...David FarrierBy David Farrier6 days ago

Hi,We’ll get to the horrific world of male diet influencers (AKA Beefy Boys) shortly, but first you will be glad to know that since I sent out the Webworm explaining why the assassination attempt on Donald Trump was not a false flag operation, I’ve heard from a load of people ...David FarrierBy David Farrier6 days ago - It's Starting To Look A Lot Like… Y2K

Do you remember Y2K, the threat that hung over humanity in the closing days of the twentieth century? Horror scenarios of planes falling from the sky, electronic payments failing and ATMs refusing to dispense cash. As for your VCR following instructions and recording your favourite show - forget about it.All ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago

Do you remember Y2K, the threat that hung over humanity in the closing days of the twentieth century? Horror scenarios of planes falling from the sky, electronic payments failing and ATMs refusing to dispense cash. As for your VCR following instructions and recording your favourite show - forget about it.All ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago - Bernard’s Saturday Soliloquy for the week to July 20

Climate Change Minister Simon Watts being questioned by The Kākā’s Bernard Hickey.TL;DR: My top six things to note around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the week to July 20 were:1. A strategy that fails Zero Carbon Act & Paris targetsThe National-ACT-NZ First Coalition Government finally unveiled ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

Climate Change Minister Simon Watts being questioned by The Kākā’s Bernard Hickey.TL;DR: My top six things to note around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the week to July 20 were:1. A strategy that fails Zero Carbon Act & Paris targetsThe National-ACT-NZ First Coalition Government finally unveiled ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - Pharmac Director, Climate Change Commissioner, Health NZ Directors – The latest to quit this m...

Summary:As New Zealand loses at least 12 leaders in the public service space of health, climate, and pharmaceuticals, this month alone, directly in response to the Government’s policies and budget choices, what lies ahead may be darker than it appears. Tui examines some of those departures and draws a long ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui1 week ago

Summary:As New Zealand loses at least 12 leaders in the public service space of health, climate, and pharmaceuticals, this month alone, directly in response to the Government’s policies and budget choices, what lies ahead may be darker than it appears. Tui examines some of those departures and draws a long ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui1 week ago - Flooding Housing Policy

The Minister of Housing’s ambition is to reduce markedly the ratio of house prices to household incomes. If his strategy works it would transform the housing market, dramatically changing the prospects of housing as an investment.Leaving aside the Minister’s metaphor of ‘flooding the market’ I do not see how the ...PunditBy Brian Easton1 week ago

The Minister of Housing’s ambition is to reduce markedly the ratio of house prices to household incomes. If his strategy works it would transform the housing market, dramatically changing the prospects of housing as an investment.Leaving aside the Minister’s metaphor of ‘flooding the market’ I do not see how the ...PunditBy Brian Easton1 week ago - A Voyage Among the Vandals: Accepted (Again!)

As previously noted, my historical fantasy piece, set in the fifth-century Mediterranean, was accepted for a Pirate Horror anthology, only for the anthology to later fall through. But in a good bit of news, it turned out that the story could indeed be re-marketed as sword and sorcery. As of ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2211 week ago

As previously noted, my historical fantasy piece, set in the fifth-century Mediterranean, was accepted for a Pirate Horror anthology, only for the anthology to later fall through. But in a good bit of news, it turned out that the story could indeed be re-marketed as sword and sorcery. As of ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2211 week ago - The Kākā's Chorus for Friday, July 19

An employee of tobacco company Philip Morris International demonstrates a heated tobacco device. Photo: Getty ImagesTL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy on Friday, July 19 are:At a time when the Coalition Government is cutting spending on health, infrastructure, education, housing ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

An employee of tobacco company Philip Morris International demonstrates a heated tobacco device. Photo: Getty ImagesTL;DR: The top six things I’ve noted around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy on Friday, July 19 are:At a time when the Coalition Government is cutting spending on health, infrastructure, education, housing ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - The Kākā’s Pick 'n' Mix for Friday, July 19

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 8:30 am on Friday, July 19 are:Scoop: NZ First Minister Casey Costello orders 50% cut to excise tax on heated tobacco products. The minister has ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

TL;DR: My pick of the top six links elsewhere around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day or so to 8:30 am on Friday, July 19 are:Scoop: NZ First Minister Casey Costello orders 50% cut to excise tax on heated tobacco products. The minister has ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - Weekly Roundup 19-July-2024

Kia ora, it’s time for another Friday roundup, in which we pull together some of the links and stories that caught our eye this week. Feel free to add more in the comments! Our header image this week shows a foggy day in Auckland town, captured by Patrick Reynolds. ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland1 week ago

Kia ora, it’s time for another Friday roundup, in which we pull together some of the links and stories that caught our eye this week. Feel free to add more in the comments! Our header image this week shows a foggy day in Auckland town, captured by Patrick Reynolds. ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland1 week ago - Weekly Climate Wrap: A market-led plan for failure

TL;DR : Here’s the top six items climate news for Aotearoa this week, as selected by Bernard Hickey and The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer. A discussion recorded yesterday is in the video above and the audio of that sent onto the podcast feed.The Government released its draft Emissions Reduction ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

- Tobacco First

Save some money, get rich and old, bring it back to Tobacco Road.Bring that dynamite and a crane, blow it up, start all over again.Roll up. Roll up. Or tailor made, if you prefer...Whether you’re selling ciggies, digging for gold, catching dolphins in your nets, or encouraging folks to flutter ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago

Save some money, get rich and old, bring it back to Tobacco Road.Bring that dynamite and a crane, blow it up, start all over again.Roll up. Roll up. Or tailor made, if you prefer...Whether you’re selling ciggies, digging for gold, catching dolphins in your nets, or encouraging folks to flutter ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago - Trump’s Adopted Son.

Waiting In The Wings: For truly, if Trump is America’s un-assassinated Caesar, then J.D. Vance is America’s Octavian, the Republic’s youthful undertaker – and its first Emperor.DONALD TRUMP’S SELECTION of James D. Vance as his running-mate bodes ill for the American republic. A fervent supporter of Viktor Orban, the “illiberal” prime ...1 week ago

Waiting In The Wings: For truly, if Trump is America’s un-assassinated Caesar, then J.D. Vance is America’s Octavian, the Republic’s youthful undertaker – and its first Emperor.DONALD TRUMP’S SELECTION of James D. Vance as his running-mate bodes ill for the American republic. A fervent supporter of Viktor Orban, the “illiberal” prime ...1 week ago - The Kākā’s Journal of Record for Friday, July 19

TL;DR: As of 6:00 am on Friday, July 19, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:The PSA announced the Employment Relations Authority (ERA) had ruled in the PSA’s favour in its case against the Ministry ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

TL;DR: As of 6:00 am on Friday, July 19, the top six announcements, speeches, reports and research around housing, climate and poverty in Aotearoa’s political economy in the last day are:The PSA announced the Employment Relations Authority (ERA) had ruled in the PSA’s favour in its case against the Ministry ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - The Hoon around the week to July 19

TL;DR: The podcast above of the weekly ‘hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers last night features co-hosts and talking with:The Kākā’s climate correspondent talking about the National-ACT-NZ First Government’s release of its first Emissions Reduction Plan;University of Otago Foreign Relations Professor and special guest Dr Karin von ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #29 2024

Open access notables Improving global temperature datasets to better account for non-uniform warming, Calvert, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society: To better account for spatial non-uniform trends in warming, a new GITD [global instrumental temperature dataset] was created that used maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to combine the land surface ...1 week ago

Open access notables Improving global temperature datasets to better account for non-uniform warming, Calvert, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society: To better account for spatial non-uniform trends in warming, a new GITD [global instrumental temperature dataset] was created that used maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to combine the land surface ...1 week ago

Related Posts

- Release: Charter schools to remove the rights of teachers

A late change to charter school legislation will cheat educators out of fair pay and negotiating power proving charter schools are just a vehicle to make profit out of our education system. ...23 hours ago

A late change to charter school legislation will cheat educators out of fair pay and negotiating power proving charter schools are just a vehicle to make profit out of our education system. ...23 hours ago - Te iwi Māori will not stand for another Foreshore and Seabed

In 2004 te iwi Māori rallied against the Crown’s attempt to confiscate our coastlines and moana with the Foreshore and Seabed Act. This led to the largest hīkoi of a generation and the birth of Te Pāti Māori. 20 years later, history is repeating itself. Today the government has announced ...2 days ago

In 2004 te iwi Māori rallied against the Crown’s attempt to confiscate our coastlines and moana with the Foreshore and Seabed Act. This led to the largest hīkoi of a generation and the birth of Te Pāti Māori. 20 years later, history is repeating itself. Today the government has announced ...2 days ago - Te Pāti Māori Acknowledge the Need for Fundamental Change in State Care

It has been five and a half years since the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care was established to investigate the abuse of children, young people, and vulnerable adults within state and faith-based institutions. Yesterday, the final report - Whanaketia through pain and trauma, from darkness to light ...2 days ago

It has been five and a half years since the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care was established to investigate the abuse of children, young people, and vulnerable adults within state and faith-based institutions. Yesterday, the final report - Whanaketia through pain and trauma, from darkness to light ...2 days ago - National disgrace for children in poverty

2 days ago

- Release: National disgrace for children in poverty

2 days ago

- Government quietly waters down child poverty targets

The Government’s move to dilute child poverty targets is a reminder that it is actively choosing to preserve hardship for thousands of households. ...2 days ago

The Government’s move to dilute child poverty targets is a reminder that it is actively choosing to preserve hardship for thousands of households. ...2 days ago - Release: National jumps on Labour’s trains

National is so short on ideas it is now announcing Labour’s rail announcement from a year ago, Labour transport spokesperson Tangi Utikere said. ...2 days ago

National is so short on ideas it is now announcing Labour’s rail announcement from a year ago, Labour transport spokesperson Tangi Utikere said. ...2 days ago - Release: Opposition parties unite to protect ECE

Labour, the Green Party and Te Pāti Māori are uniting to stop the Government’s dangerous changes to the Early Childhood Education sector. ...2 days ago

Labour, the Green Party and Te Pāti Māori are uniting to stop the Government’s dangerous changes to the Early Childhood Education sector. ...2 days ago - Release: Another step forward for survivors of abuse in care

Labour welcomes the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care’s final report and the government committing to a formal apology in November. ...3 days ago

Labour welcomes the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care’s final report and the government committing to a formal apology in November. ...3 days ago - Govt must listen to experiences of abuse survivors

The Government must do all it can to bring abuse in care to an end following the release of the independent inquiry. ...3 days ago

The Government must do all it can to bring abuse in care to an end following the release of the independent inquiry. ...3 days ago - Release: Health New Zealand exposes Minister spinning in freefall

Health New Zealand contradicted the Government’s spin that back-office bureaucracy is the cause of overspend in the public health system. ...4 days ago

Health New Zealand contradicted the Government’s spin that back-office bureaucracy is the cause of overspend in the public health system. ...4 days ago - Govt must act on Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestine

The Green Party is calling on the Government to take action off the back of the International Court of Justice ruling on Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestine. ...4 days ago

The Green Party is calling on the Government to take action off the back of the International Court of Justice ruling on Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestine. ...4 days ago - NZ Government Must Enforce ICJ Ruling

On Friday the International Court of Justice reaffirmed what Palestinian’s have been telling us for decades: that the occupation and colonisation of Palestinian lands by Israel is illegal and must end immediately. They also called for reparations for Palestinian’s who have lived under Israeli occupation since it began in 1967. ...5 days ago

On Friday the International Court of Justice reaffirmed what Palestinian’s have been telling us for decades: that the occupation and colonisation of Palestinian lands by Israel is illegal and must end immediately. They also called for reparations for Palestinian’s who have lived under Israeli occupation since it began in 1967. ...5 days ago - Release: Listen PM, boot camps don’t work

Refusing to listen to evidence, experts or experience the Government is stubbornly marching ahead with its boot camps. ...7 days ago

Refusing to listen to evidence, experts or experience the Government is stubbornly marching ahead with its boot camps. ...7 days ago - Release: Govt must act on ICJ ruling on illegal Israeli occupation

Labour calls on the Government to act after the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled that Israel’s occupation of Palestinian Territories is illegal. ...7 days ago

Labour calls on the Government to act after the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled that Israel’s occupation of Palestinian Territories is illegal. ...7 days ago - Release: Rents up under National, promises fall flat

National Party policies which promised to put “downward pressure” on rents are having the opposite effect. ...1 week ago

National Party policies which promised to put “downward pressure” on rents are having the opposite effect. ...1 week ago - MSD figures show Govt determined to punish beneficiaries

The 53.7 percent rise in benefit sanctions over the last year is more proof of this Government’s disdain for our communities most in need of support. ...1 week ago

The 53.7 percent rise in benefit sanctions over the last year is more proof of this Government’s disdain for our communities most in need of support. ...1 week ago - We need real solutions, not more failed boot camps – Willow-Jean Prime

Aotearoa could be a country where every child grows up feeling safe, loved and with a sense of belonging in their whānau and community. But for some of our children, this is far from reality. Instead, they are trapped in a maze of intergenerational harm that they can’t escape on ...1 week ago

Aotearoa could be a country where every child grows up feeling safe, loved and with a sense of belonging in their whānau and community. But for some of our children, this is far from reality. Instead, they are trapped in a maze of intergenerational harm that they can’t escape on ...1 week ago - David Seymour is Unfit to Serve as Minister

Te Pāti Māori are calling for David Seymour to resign as Associate Health Minister in response to his call for Pharmac to ignore the Treaty of Waitangi. “This announcement is just another example of the government’s anti-Tiriti, anti-Māori agenda.” Said Co-leader and spokesperson for health, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer. “Seymour thinks it ...1 week ago

Te Pāti Māori are calling for David Seymour to resign as Associate Health Minister in response to his call for Pharmac to ignore the Treaty of Waitangi. “This announcement is just another example of the government’s anti-Tiriti, anti-Māori agenda.” Said Co-leader and spokesperson for health, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer. “Seymour thinks it ...1 week ago - Renters suffer as soaring rents feed rising inflation

The soaring price of renting is driving the rise of inflation in this country - with latest figures from Stats NZ showing rents are up 4.8 per cent on average while annual inflation is at 3.3 per cent. ...1 week ago

The soaring price of renting is driving the rise of inflation in this country - with latest figures from Stats NZ showing rents are up 4.8 per cent on average while annual inflation is at 3.3 per cent. ...1 week ago - National’s climate strategy undoes good progress

National’s Emissions Reduction Plan will take New Zealand further from the economy we need to ensure the next generation has a stable climate and secure livelihoods. ...1 week ago

National’s Emissions Reduction Plan will take New Zealand further from the economy we need to ensure the next generation has a stable climate and secure livelihoods. ...1 week ago - Green Party releases executive summary of independent investigation

Following consultation with named parties and thorough consideration of privacy interests, the Green Party is in a position to release the Executive Summary of the final report from the independent investigation into Darleen Tana. ...1 week ago

Following consultation with named parties and thorough consideration of privacy interests, the Green Party is in a position to release the Executive Summary of the final report from the independent investigation into Darleen Tana. ...1 week ago - Government back off track on climate action

Today’s Draft Emissions Reduction Plan shows the Government couldn’t care less about a liveable climate for all. ...1 week ago

Today’s Draft Emissions Reduction Plan shows the Government couldn’t care less about a liveable climate for all. ...1 week ago - PM needs to step in over Shane Jones’ undeclared meeting

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon should be asking serious questions of his Minister for Resources Shane Jones now it’s been revealed he misled the public about a dinner with mining companies that he didn’t declare and said wasn’t pre-arranged. ...2 weeks ago

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon should be asking serious questions of his Minister for Resources Shane Jones now it’s been revealed he misled the public about a dinner with mining companies that he didn’t declare and said wasn’t pre-arranged. ...2 weeks ago - Te Pāti Māori Opposes Three Strikes Amendment Bill

Te Pāti Māori have submitted to the Justice Select Committee against the Sentencing (Reinstating Three Strikes) Amendment Bill. The bill will further entrench racism in our justice system and fails to focus on rehabilitation. “Reinstating Three Strikes will empower a systematically racist system and exacerbate the overrepresentation of Māori in ...2 weeks ago

Te Pāti Māori have submitted to the Justice Select Committee against the Sentencing (Reinstating Three Strikes) Amendment Bill. The bill will further entrench racism in our justice system and fails to focus on rehabilitation. “Reinstating Three Strikes will empower a systematically racist system and exacerbate the overrepresentation of Māori in ...2 weeks ago - Govt Determined to Make Aotearoa a Country of Disposable Renters

The Transport and Infrastructure Committee is set to make a determination on the Residential Tenancies Amendment (RTA) Bill in the coming weeks. “This legislation will give landlords the power to kick our whānau out onto the street for no reason” said Housing spokesperson, Mariameno Kapa-Kingi. “Their solution to the housing ...2 weeks ago

The Transport and Infrastructure Committee is set to make a determination on the Residential Tenancies Amendment (RTA) Bill in the coming weeks. “This legislation will give landlords the power to kick our whānau out onto the street for no reason” said Housing spokesperson, Mariameno Kapa-Kingi. “Their solution to the housing ...2 weeks ago - Statement on retail crime Ministerial Advisory Group

“National’s campaign was about tackling crime and the best they can do is a two-year long Ministerial Advisory Group,” Labour justice spokesperson Duncan Webb said. ...2 weeks ago

“National’s campaign was about tackling crime and the best they can do is a two-year long Ministerial Advisory Group,” Labour justice spokesperson Duncan Webb said. ...2 weeks ago - Statement from Labour education spokesperson Jan Tinetti

“There are more examples of charter schools failing their students than there are success stories. The coalition Government is driving to dismantle our public school system and instead promote a privatised, competitive structure that puts profits before kids,” Jan Tinetti said. ...2 weeks ago

“There are more examples of charter schools failing their students than there are success stories. The coalition Government is driving to dismantle our public school system and instead promote a privatised, competitive structure that puts profits before kids,” Jan Tinetti said. ...2 weeks ago - Govt Continues to Destructively Withhold Information

“This government is choosing to deliberately mislead and withhold information, keeping our people in the dark about this government’s agenda and the future of our mokopuna,” said co-leader and spokesperson for Health, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer. The call comes after the demand from the Chief Ombudsman that Associate Minister of Health, Casey ...2 weeks ago

“This government is choosing to deliberately mislead and withhold information, keeping our people in the dark about this government’s agenda and the future of our mokopuna,” said co-leader and spokesperson for Health, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer. The call comes after the demand from the Chief Ombudsman that Associate Minister of Health, Casey ...2 weeks ago - Statement from Labour climate change spokesperson Megan Woods

“Today’s climate announcement by Simon Watts makes clear the National Government is simply paying lip service to meeting its climate change targets,” Megan Woods said. ...2 weeks ago

“Today’s climate announcement by Simon Watts makes clear the National Government is simply paying lip service to meeting its climate change targets,” Megan Woods said. ...2 weeks ago - Eight ways National is making life harder for workers

National is choosing to make life harder for workers by taking away the rights our communities have fought hard for. Here's how they’re taking workers backwards. ...3 weeks ago

National is choosing to make life harder for workers by taking away the rights our communities have fought hard for. Here's how they’re taking workers backwards. ...3 weeks ago - Waitlists up and workforce down under National

Health New Zealand’s recent quarterly performance report shows the public health system is going backwards under the National government. ...3 weeks ago

Health New Zealand’s recent quarterly performance report shows the public health system is going backwards under the National government. ...3 weeks ago

Related Posts

- Joint statement from the Prime Ministers of Canada, Australia and New Zealand

Australia, Canada and New Zealand today issued the following statement on the need for an urgent ceasefire in Gaza and the risk of expanded conflict between Hizballah and Israel. The situation in Gaza is catastrophic. The human suffering is unacceptable. It cannot continue. We remain unequivocal in our condemnation of ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz17 hours ago

Australia, Canada and New Zealand today issued the following statement on the need for an urgent ceasefire in Gaza and the risk of expanded conflict between Hizballah and Israel. The situation in Gaza is catastrophic. The human suffering is unacceptable. It cannot continue. We remain unequivocal in our condemnation of ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz17 hours ago - AG reminds institutions of legal obligations

Attorney-General Judith Collins today reminded all State and faith-based institutions of their legal obligation to preserve records relevant to the safety and wellbeing of those in its care. “The Abuse in Care Inquiry’s report has found cases where records of the most vulnerable people in State and faith‑based institutions were ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz20 hours ago

Attorney-General Judith Collins today reminded all State and faith-based institutions of their legal obligation to preserve records relevant to the safety and wellbeing of those in its care. “The Abuse in Care Inquiry’s report has found cases where records of the most vulnerable people in State and faith‑based institutions were ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz20 hours ago - More young people learning about digital safety

Minister of Internal Affairs Brooke van Velden says the Government’s online safety website for children and young people has reached one million page views. “It is great to see so many young people and their families accessing the site Keep It Real Online to learn how to stay safe online, and manage ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz20 hours ago

Minister of Internal Affairs Brooke van Velden says the Government’s online safety website for children and young people has reached one million page views. “It is great to see so many young people and their families accessing the site Keep It Real Online to learn how to stay safe online, and manage ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz20 hours ago - Speech to the Conference for General Practice 2024

Tēnā tātou katoa, Ngā mihi te rangi, ngā mihi te whenua, ngā mihi ki a koutou, kia ora mai koutou. Thank you for the opportunity to be here and the invitation to speak at this 50th anniversary conference. I acknowledge all those who have gone before us and paved the ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz22 hours ago

Tēnā tātou katoa, Ngā mihi te rangi, ngā mihi te whenua, ngā mihi ki a koutou, kia ora mai koutou. Thank you for the opportunity to be here and the invitation to speak at this 50th anniversary conference. I acknowledge all those who have gone before us and paved the ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz22 hours ago - Employers and payroll providers ready for tax changes

New Zealand’s payroll providers have successfully prepared to ensure 3.5 million individuals will, from Wednesday next week, be able to keep more of what they earn each pay, says Finance Minister Nicola Willis and Revenue Minister Simon Watts. “The Government's tax policy changes are legally effective from Wednesday. Delivering this tax ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz1 day ago

New Zealand’s payroll providers have successfully prepared to ensure 3.5 million individuals will, from Wednesday next week, be able to keep more of what they earn each pay, says Finance Minister Nicola Willis and Revenue Minister Simon Watts. “The Government's tax policy changes are legally effective from Wednesday. Delivering this tax ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz1 day ago - Experimental vineyard futureproofs wine industry

An experimental vineyard which will help futureproof the wine sector has been opened in Blenheim by Associate Regional Development Minister Mark Patterson. The covered vineyard, based at the New Zealand Wine Centre – Te Pokapū Wāina o Aotearoa, enables controlled environmental conditions. “The research that will be produced at the Experimental ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz1 day ago