This essay is dedicated to the memory of Herman Daly, the father of ecological economics, who began writing about the absurdity of perpetual economic growth in the 1970s; Herman died on October 28 at age 84.

Politicians and economists talk glowingly about growth. They want our cities and GDP to grow. Jobs, profits, companies, and industries all should grow; if they don’t, there’s something wrong, and we must identify the problem and fix it. Yet few discuss doubling time, even though it’s an essential concept for understanding growth.

Doubling time helps us grasp the physical meaning of growth—which otherwise appears as an innocuous-looking number denoting the annual rate of change. At 1 percent annual growth, any given quantity doubles in about 70 years; at 2 percent growth, in 35 years; at 7 percent, in 10 years, and so on. Just divide 70 by the annual growth rate and you’ll get a good sense of doubling time. (Why 70? It’s approximately the natural logarithm of 2. But you don’t need to know higher math to do useful doubling-time calculations.)

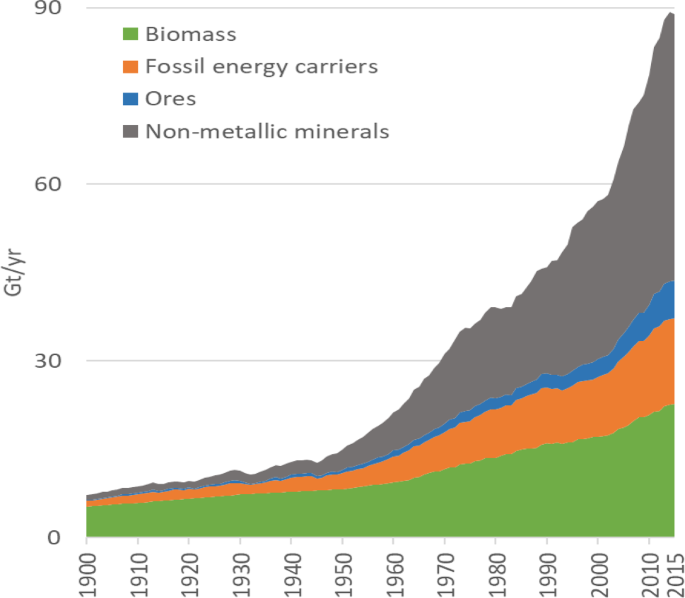

Here’s why failure to think in terms of doubling time gets us into trouble. Most economists seem to believe that a 2 to 3 percent annual rate of growth for economies is healthy and normal. But that implies a doubling time of roughly 25 years. When an economy grows, it uses more physical materials—everything from trees to titanium. Indeed, the global economy has doubled in size in the last quarter-century, and so has total worldwide extraction of materials. Since 1997 we have used over half the non-renewable resources extracted since the origin of humans.

As the economy grows, it also puts out more waste. In the last 25 years, the amount of solid waste produced globally has soared from roughly 3 million tons per day to about 6 million tons per day.

Global materials extraction and usage, 1900 to 2015. Source: Arnulf Grubler, Technological and Societal Changes and Their Impacts on Resource Production and Use.

NOTE: higher res version here: https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S0959378017313031-gr2_lrg.jpg.

Further, if the economy keeps growing at the recent rate, in the next 25 years we will approximately double the amount of energy and materials we use. And by 50 years from today our energy and materials usage will have doubled again, and will therefore be four times current levels. In a hundred years, we will be using 16 times as much. If this same 2 to 3 percent rate of growth were to persist for a century beyond that, by the year 2222 we’d be using about 250 times the amount of physical resources we do now, and we’d be generating about 250 times as much waste.

Population growth can also be described in terms of doublings. Global human population has doubled three times in the past 200 years, surging from 1 billion in 1820 to 2 billion in 1927, to 4 billion in 1974, to 8 billion today. Its highest rate of growth was in the 1960s, at over 2 percent per year; that rate is now down to 1.1 percent. If growth continues at the current rate, we’ll have about 18 billion people on Earth by the end of this century.

All of this would be fine if we lived on a planet that was itself expanding, doubling its available quantities of minerals, forests, fisheries, and soil every quarter-century, and doubling its ability to absorb industrial wastes. But we don’t. It is essentially the same beautiful but finite planet that was spinning through space long before the origin of humans.

Young people might think of 25 years as a long time. But, given the centuries it takes to regrow a mature forest, or the millennia it takes to produce a few inches of topsoil, or the tens of millions of years it took nature to produce fossil fuels, 25 years is a comparative eyeblink. And in that eyeblink, humanity’s already huge impact on Earth’s finely balanced ecosystems doubles.

Since resources are finite, the doubling of humanity’s rates of extracting them can’t go on forever. Economists try to get around this problem by hypothesizing that economic growth can eventually be decoupled from greater usage of resources. Somehow, according to the hypothesis, GDP (essentially a measure of the amount of money flowing through the economy) will continue to climb, but we’ll spend our additional money on intangible goods instead of products made from physical stuff. So far, however, the evidence shows that decoupling hasn’t occurred in the past and is unlikely to happen in the future. Even cryptocurrencies, seemingly the most ephemeral of goods, turn out to have a huge material footprint.

As long as we continue to pursue growth, we are on track to attempt more doublings of resource extraction and waste dumping. But, at some point, we will come up short. When that final doubling fails, a host of expectations will be dashed. Investment funds will go broke, debt defaults will skyrocket, businesses will declare bankruptcy, jobs will disappear, and politicians will grow hoarse blaming one another for failure to keep the economy expanding. In the worst-case scenario, billions of people could starve and nations could go to war over whatever resources are left.

Nobody wants that to happen. So, of course, it would help to know when the last doubling will begin, so we can adjust our expectations accordingly. Do we have a century or two to think about all of this? Or has the final, ill-fated doubling already started?

Forecasting the Start of the Final Doubling—It’s Hard!

One of the problems with exponential acceleration of consumption is that the warning signs of impending resource scarcity tend to appear very close to the time of actual scarcity. During the final doubling, humanity will be using resources at the highest rates in history—so it will likely seem to most people that everything is going swimmingly, just when the entire human enterprise is being swept toward a waterfall.

Trying to figure out exactly when we’ll go over the falls is hard also because resource estimates are squishy. Take a single mineral resource—copper ore. The US Geological Survey estimates global copper reserves at 870 million metric tons, while annual copper demand is 28 million tons. So, dividing the first number by the second, it’s clear that we have 31 years’ worth of copper left at current rates of extraction. But nobody expects the global rate of copper mining to stay the same for the next 31 years. If the rate of extraction were to grow at 2.5 percent per year, then current reserves would be gone in a mere 22 years.

But that’s a simplistic analysis. Lower grades of copper ore, which are not currently regarded as commercially viable, are plentiful; with added effort and expense those resources could be extracted and processed. Further, there is surely more copper left to be discovered. A key bit of evidence in this regard is the fact that copper reserves have grown in some years, rather than diminishing. (On the other hand, the World Economic Forum has pointed out that the average cost of producing copper has risen by over 300 percent in recent years, while average copper ore grade has dropped by 30 percent.)

What if we were to recycle all the copper we use? Well, we should certainly try. But, disregarding any practical impediments, there’s the harsh reality that, as long as usage rates are growing, we’ll still need new sources of the metal, and the rate at which we’re depleting reserves will increase.

If all else fails, there are other metals that can serve as substitutes for copper. However, those other metals are also subject to depletion, and some of them won’t work as well as copper for specific applications.

Altogether, the situation is complicated enough that a reliable date for “peak copper,” or for when copper shortages will cause serious economic pain, is hard to estimate. This uncertainty, generalized to apply to all natural resources, leads some resource optimists to erroneously conclude that humanity will never face resource scarcity.

Here’s the thing though: if extraction is growing at 3 percent annually for a given resource, any underestimate won’t be off by very many years. That’s due to the power of exponentially growing extraction. For example, let’s say an analyst underestimates unobtanium reserves by half. In other words, there’s twice as much unobtanium in the ground as the analyst predicted. The date of the last bit of unobtanium extraction will only be 25 years later than what was forecast. Underestimating the abundance of a resource by three-quarters implies a run-out date that’s only 50 years too soon.

We’re In It

Resource depletion isn’t the only limit to the continued growth of the human enterprise. Climate change is another threat capable of stopping civilization in its tracks.

Our planet is warming as a result of greenhouse gas emissions—pollutants produced mainly by our energy system. Fossil fuels, the basis of that system, are cheap sources of densely stored energy that have revolutionized society. It’s because of fossil fuels that industrial economies have grown so fast in recent decades. In addition to causing climate change, fossil fuels are also subject to depletion: oilfields and coalmines are typically exhausted in a matter of decades. So, virtually nobody expects that societies will still be powering themselves with coal, oil, or natural gas a century from now; indeed, some experts anticipate fuel supply problems within years.

The main solution to climate change is for society to switch energy sources—to abandon fossil fuels as quickly as possible and replace them with solar and wind power. However, these alternative energy sources require infrastructure (panels, turbines, batteries, expanded grids, and new electrically powered machinery such as electric cars and trucks) that must be constructed using minerals and metals, many of which are rare. Some resource experts doubt that there are sufficient minerals to build an alternative energy system on a scale big enough to replace our current fossil-fueled energy system. Simon Michaux of the Finnish Geological Survey declares flatly that, “Global reserves are not large enough to supply enough metals to build the renewable non-fossil fuels industrial system.” Even if Michaux’s resource estimates are too pessimistic, it is still probably unrealistic to imagine that a renewables-based energy system will be capable of doubling in size even once, much less every 25 years forever more.

So, if another doubling of the global economy is impossible, that means the last doubling is already under way, and perhaps even nearing its conclusion.

It is better to anticipate the final doubling too soon rather than too late, because it will take time to shift expectations away from continuous growth. We’ll have to rethink finance and government planning, rewrite contracts, and perhaps even challenge some of the basic precepts of capitalism. Such a shift might easily require 25 years. Therefore, we should begin—or already should have begun—preparing for the end of growth at the start of the final doubling, at a time when it still appears to many people that energy and resources are abundant.

Re-localize, reduce, repair, and reuse. Build resilience. Become more independent of the monetary economy in any neighborly ways you can.

______________________________________________________

No more needs to be said.

One of the best things I've ever read explaining this (in terms of clarity and making it accessible to a range of people's understandings about the economy and the planet).

Bloody scary, laid out like that. Humans will not cope well.

The following two references suggest a much lower number of around 10 billion.

https://ourworldindata.org/future-population-growth#global-population-growth

https://www.populationpyramid.net/world/2100/

A lot of unknowns – such as the impact of COVID on lifespan.

1950 to 2021 births

Asian 57-67M per annum.

Africa 11-45M per annum.

Rest 24-21M per annum.

Any change in the African mortality rate (improved health and longevity) would have an increasing impact.

It's little wonder the African Union is to become an add on to the G20.

One wonders as to the carbon impact of the urbanisation in that continent.

Virtually all the population growth this century will be in Africa; so I would agree the projections are very sensitive to what happens there:

https://www.populationpyramid.net/africa/2019/

But almost everywhere else populations have pretty much peaked are are in decline:

https://www.populationpyramid.net/europe/2019/

https://www.populationpyramid.net/china/2019/

https://www.populationpyramid.net/asia/2019/

Human beings do not behave like bacteria in a petrie dish.

Urbanisation in a continent with a rising population has carbon use/GW consequences (the same in India as it follows China on the urbanisation path).

It is essentially a idiotic argument that Richard Heinberg is making, based completely on exponential growth without looking at economic behaviour, the causes of innovation, what triggers recycling and reuse, and what causes populations to start and stop growing.

As RL implies arguing on the basis of 18 billion population at the end of the century is completely ridiculous.

Within my lifetime the rate of population growth worldwide has slowed from a double replacement of >2 children per child rearing adult to below the replacement rate (at 1.1 once you factor in accidents before progenation, fertility rates, and people who simply don't have children). The only reason that we still have a rising world population at present is because of those population replacement rates in the 1960s and 1970s. There is still a population bulge running through of children of the 60s having more limited number of children, and their children having fewer again.

Essentially all areas apart from Africa are currently not replacing their existing populations once you factor that 50s-70s age bulge in almost every part of the world. Africa itself had lower than expected population growths compared to the other regions of the world through most of the last part of the 20th century. That is likely due to a combination of endemic HIV/AIDs and other diseases, post-colonial warfare, and that as the only major equatorial landmass that it has had continuous extreme climate change since the temperature drops at the end of the Holocene hotspot ~5000 years ago.

Africa is now showing signs of a braking fertility, just as the rest of the world is showing signs of joining it in extreme climatic change events.

Reusable resources like copper being used in a economic system get changed usage according to their effort to be extracted. Sure, when we have a rising population the pool of available reusable copper gets increased by mining and refining. As easily accessible resources are used up (and remember that in the neolithic, copper 'mines' were places where raw almost pure copper was able to be picked up at the surface by hand), the effort to extract new mineral resources increases. When that happens, the already mined copper not in use becomes used more.

Not to mention that higher costs have an immediate effect of causing innovation in how to use less. Instead of using solid drawn wires for power, smaller stranded wires are used. Old electronic boards within my lifetime used to use wire strands. Now they use trace impurities.

Plus the falling populations that we already have in the developed nations now means that there is a lot of currently in-use copper going to be available for scavenging. That is why most of the recycled copper makes it way from developed countries to ones who are building their infrastructure up.

Then consider where copper is currently being used in a rising population world. Currently something like 40% of the worlds copper going into new manufacture is recycled copper. And when we have a falling population there is less need to create new power generation, distribution and transmission or to expand transport systems. That is around 65+% of all copper usage at present. When the infrastructure equalises out across the world, then that 65% will drop to maintenance and upgrade levels and demand falls drastically.

Population growth is the driver for all new material additions for recyclable resources. To ignore it, as Heinberg has done in this silly exponential growth thought experiment, is to ignore that exponential growth over any longer time periods is something that simply doesn't exist. Similarly, over the last three centuries, minerals have repeatably promoted as being a constraint on population growth. It simply hasn't happened.

You can easily find projections of copper running out since the 18th century and throughout the whole 20th century. On a fully recyclable material? They really are nuts. I can't think of a faster way than rising extraction costs to cause innovation and lower consumption patterns. In fact I can't think of any minerals

Virtually every growth system follows S curves of some form when new resources open up – in the human case from societal innovation that resulted in scientific innovation. The constraint at the top of a S curve shows as soon as a resource constraint is found. You can't see a single one over the last 3 centuries. Currently the only effective constraint displaying for population is that people aren't wanting to have spare kids when they don't drop dead so often.

Sure this doesn't happen with non-recyclable minerals like fossil hydrocarbon or fossil radioactives. Eventually having to tap the supply for new sources all of the time will eventually cause the extraction cost to rise high enough to cause constraint or a change in usage.

But there are a lot of reasons to not use non-recyclable minerals anyway – the waste byproducts are where the real cost shows up. Especially since these waste products cause issues that are visible at geological time scales.You can’t clean them up in human lifetimes. You have to plan on fixing them up over thousands of years.

Climate change from burning fossil fuels is ridiculously expensive to deal with.

Cleaning up nuclear waste sites like Sellafield (and thousands of others scattered world wide) was the 'solved' problem of Edward Teller in 1956. That simply hasn't effectively 'solved' anywhere in the intervening decades. The Finns are the first to have what looks like a properly designed geological disposal site actually working. But no-one knows if it will be any better than the sites and trials that have failed in miserably the past. It will also take decades of sceptical analysis of that and other new geological storage systems to decide if they get around the major problem known about nuclear electricity systems.

But what is clear is that if full nuclear disposal was an accounted project cost at the start of almost any nuclear power project, then nuclear power was the most expensive possible electricity supply option. Since most current new technology nuclear power projects also seem to be very light on how to clean up their waste properly, I think that they should be treated as prototypes unsuitable for wide release only. We shouldn't believe any modern day Edward Teller. Their track record for responsible engineering absolutely sucks.

Agree on almost all points.

I responded to the nuclear power question elsewhere.

And very recently a new author – albeit he is 90 yrs old – has popped up in the pro-nuclear space who I'm finding challenging and thought provoking.

Yeah, Jack whatever his name simply doesn't understand the issue of how to deal with containment over time. He is a idiot focused on the short-term and obsessed by power generation rather than making the environment reasonably safe from nuclear waste de-containment over the next 500 years..

Think of it like this. If he and every nuclear engineer that I have ever read on containment on waste issues was alive as an engineer in the court of James 1st of England – they'd be confident that

This is essentially the position of nuclear engineers now when looking at containment. As someone who spends a lot of time reading history, and trained in thinking in geological timescales – that just reeks of stupidity. Both geology and reading history teach you that the everything changes.

It isn't a case of if containment of nuclear waste will get breached – it is a case of when it will. It is also a case of limiting how much damage gets caused when it does.

Nuclear engineers have a track record of never bothering to think about that any more than Edward Teller did back in 1956.

I was hoping to continue this discussion on the other Open Mike thread. It might be regarded as 'irrelevant' here.

It would pay to read what is written inits entirety.

18 billion at the current growth rate…however if we are already in overshoot this is the final doubling and that total will not be reached because reasons explained.

"So, if another doubling of the global economy is impossible, that means the last doubling is already under way, and perhaps even nearing its conclusion."

As to materials and energy Simon Michaux has outlined the same issues.

https://www.reddit.com/r/collapse/comments/vja57q/nate_hagens_interviews_scientist_studying_mineral/

The reason why population is projected to peak at around 10b (and I personally think it may well come in under this) is because industrialisation and urbanisation has dramatically cut fertility everywhere. Not because of famine or mass death.

As for the resources and materials constraint – as Lynn points out – this is an old prediction that has repeatedly failed to deliver. What happens is that as soon as market signals suggest we are reaching a resource constraint, we shift to an alternative. Either a more efficient implementation, recycling or a new technology.

Here for example are three decent alternatives to copper in electrical applications.

The reasons for population growth decline are many including resource constraint…and there are tipping points. All well canvases by Donella Meadows in her work on systems.

The 'old prediction that has failed to deliver' has been delayed by the type of substitution you promote…that substitution is evidence of resource constraint and only delays events…eventually all substitutes meet the same problems…i.e aluminium as a conductor , the constraint will not be the bauxite but the energy/processes that are increasingly constraining all activity at the required level.

Rationing has to date been achieved by price….Id suggest we have entered the era where rationing will be achieved by more direct and difficult decisions….and that will only buy a little time…..if we are lucky.

I do not understand this – fertility rates peaked in 1968 (even Heinberg acknowledges this) and have been declining ever since. Are you say this is because of resource constraints?

How would that work when in the pre-Industrial era where resources were far more constrained and everyone was dirt poor – they always had far more children?

Im saying that fertility rates are influenced by many factors….including resource constraint.

The degree of influence of individual factors will vary with both location and time.

Pre industrially the constraints were of capability not of reserves….and larger families were a feature (and still are in some locations) until relatively recently, certainly post industrial revolution.

So is the cure LESS people or less stuff used per person?

OR do we just continue to take stuff away from many more people so that the few can live the high life?

living within our means. Steady state economies with or without degrowth. Doughnut economics. Being real about physical reality and developing economics based on that. There are a lot of people doing work on this, from the edge and within the mainstream. It's not in politics or the MSM much yet.

Resources generally do not disappear when used they merely change form. The question then becomes whether we expend effort and energy to extract the resource from the by-product or we use more readily accessible forms of the resource. We are only restricted by technology and energy and in relation to energy we have far more than we can hope to use.

Resources do disappear. If you chop down a forest, it is gone. It takes decades to replace it and old growth forest takes much longer. If the timber from the forest is made into something short lived and single use eg paper, then it too all intents and purposes disappears both as part of an ecological loop, or as something humans can use over time. eg it is burned or sent to degrade in a landfill.

Even if humans choose to "to extract the resource from the by-product", eg to recycle the paper, that process itself takes energy and produces waste, as well as generally producing a product of a lesser order.

This is only true as an abstract. In reality, energy is lost all the time and the materials we rely on (forests, precious metals, sand, whatever) don't obey the rules you are trying to lay down. We are limited by the physicality of the universe and by the paucity of our imaginations and our unwillingness to work within the container of nature. That limitation isn't a bad thing if one uses sustainable design principles, in fact that kind of design is more inline with what you are talking about because it uses the energy loops and flows inherent in nature. But unlike your philosophy it doesn't ignore the meaning of the material world.

One of the requirements for right wing views, is to ignore concepts such as entropy.

Entropy only matters in a closed system. The Earth is not a closed system when it comes to energy. We don't have to worry about running out for billions of years.

Unfortunately you make a fundamental error…we are indeed a closed system.

All that free energy has to be converted, either biologically or technologically….both are limited.

I'm with Gosman on this. There's energy pouring in on us, yes? no?

Which, if we captured more than a small fraction, the earth would be a fireball.

Venus is an example of capturing too much energy.

However the resources required to use that energy, will run out eons before the energy does.

For most mineral resources, they don't go away. They are there and available to recycle within whatever civilisation is around. The reason that we've been mining so much in the last 5 centuries is because humans managed to figure out techniques to increase their population.

The mining took off to service the expanded population because recycling doesn't cope with expanded populations. When you look at periods when populations are static or falling (the aftermath centuries of the black death across eurasia being a good example), you find mines being abandoned.

You can see the same change in pace for mining in the past whenever there is population increase in an area. Mining starts or resumes on recyclable mineral mining sites.

The exceptions are in consumed minerals like salt and tars. Even during times of human diebacks you can see those mining activities continuing.

So population changes are always the main operand for recyclical mineral mining activity

I suggest you listen to the interview with Simon Michaux…you cant recycle something that hasnt been created and recycling itself is a finite process…you expend both energy and capability /capacity and also lose quality …it is not an ad infinitum process.

Isn't the universe recycling constantly, the materials created at the point of big-bang?

Are you suggesting that new materials are being added, daily?

Are you suggesting they are not?

Are you saying that humans will still be around over that time scale?

A fantasy common to Randites like Musk, that they will subvert mortality.

Not created – you mean possibly mean 'mined' or 'extracted'. There are very few places where elements are actually created out of various types of particles. Slightly more places where minerals are formed.

However if you read my comments. Mining by humans has a direct relationshop with human population growth. If you had a

You really need to be kind of careful specifying your frameworks especially when you're assert something to someone interested in earth sciences, physics, chemistry, or cosmology.

As Robert points out, everything material is recycled already.

The continents push material into the upper mantle and spew it out of non-basaltic volcanoes. The core routes heavy elements up from the lower mantle in magma geysers. The core itself mixes itself into lower mantle as it discards radioactive heat.

We are orbiting a generation III star. Almost everything in it has been recycled at least a couple of times in gas clouds, exploded stars and their nebulas. Most everything will tend to agglomerate under gravity and most likely be recycled somewhere. There are some interesting interactions even with black holes which don't look that persistent over very long time frames.

What you are probably trying to articulate and describe is largely a economic framework in the present day. Recycling is not a particularly loss creating process if you have sufficient energy. Because after all mining itself is just another recycling process.

At an atomic level, atoms aren't known for their ability to be lost as a element outside of inside of sun (where they make different elements) or a neutron star (seas of smaller particles) or a black hole (who knows) – or whenre they are an unstable isotope within a given time frame.

You can grab almost any element and with energy and knowledge of physical and chemical properties – extract pure elements out of the most mixed up messes. This is after all how we extract them now.

We are long past the days when our neolithic ancestors could pick up on the earth surface nearly pure veins of copper or gold or silver out of rock.

For centuries we extract have extracted copper and every other element at very low purity rates out of rubbish rock or sediments.

These days copper is mined from ores with a concentration of copper of less than 1%.

If you look back say 180 years ago, we only mined copper directly out of veins of rock – probably typically around 5% concentration of the rock extracted at a much lower expenditure of energy.

An electronics graveyard has a copper concentration that is way way more than 1%. After one of our current waste disposal areas has compacted a bit and bled off organics – they will probably wind up with copper concentrations approaching 0.1%. Not a large step.

Copper is about 0.09 ppm in seawater. If we got a concentrated source of energy, (fusion, renewable/battery) of a break though in ionic filtering it wouldn't surprise me if we could recycle copper out of seawater in 180 years. It isn't that hard. Cuttlefish have copper based blood where the copper is filtered out of seawater. In fact we can do this now quite easily with current technologies. But…

It'd be more currently expensive in energy terms for humans to do it than the way the cuttle fish do it. But what we do now to extract copper is way harder and more expensive in energy that the way it was done 180 years ago.

And that leads back to economics. Now perhaps you can have a look at the need for certain minerals in economic terms and then look at costs to extract and refine it. This is a classic problem of break evens. So if we need Yttrium or Copper for something, the the price will go up. As it does, then innovation will get funded to make it economic or to find an alternative.

With copper, we can use aluminium for almost all cases that we need it for. In electricity or electricity, the common aluminium alloys are less ductile and requires more heat handling. But that is just a cost in the BOM. You can guarantee that the price for dealing with that will drop like a stone if the cost of extracting 'fresh' copper rises. You can also guarantee that there will be a rush of copper out of existing installations and its replacement by

The same applies to every other element or mineral. Possibly except for the radioactive ones or where we're getting cheap chemical energy from. Those would require energy inputs to store potential energy. There isn't really a point – it is almost invariably simpler to directly use the energy directly stored more efficiently.

So if you want to make the stupid assertion

You are dead wrong – unless you want to specify a very long time period – as in billions of years. You’re not even really right is it was looking at human timescales. Most of the time now we already know how to extract anything at almost any concentration from multiple sources. It just becomes a matter of making it worth doing so. Moreover we also usually know ways to work around needing a particular mineral – also at a cost.

But hey, if you’re justy trying to say that you’re cheap, kind of lazy and conservative. Well yep that does show up in your attitudes and understanding of the universe and world you live in.

Yes again this lines up closely with my understanding as well. The only point I would like to underline is that recycling most resources is indeed a simple matter of energy economics.

Setting aside your objection to nuclear energy that we have debated elsewhere, this is one of the critical benefits that would flow from clean, abundant and cheap electricity – the opportunity to effectively recycle virtually any resource we needed.

All that is wonderful…some if may even be correct but you miss the fundamental point of doubling….all the recycling in the world dosnt create 2 tonnes of (e.g) copper when you start with 1 tonne….and there are loses in the recycling process, even for copper.

Michaux's case is there are insufficient minerals (subsequently materials) available to replace the energy fossil fuels currently provide….consequently we will have (considerably) less energy available….and recycling requires energy, along with all the competing uses

NZ produces approx 0.5% of the worlds aluminium and expends 13% of its electricity generation to do so.

I think that you're completely missing the point.

What we are are mining at present is teeny fraction of the accessible and economic atoms of every material. Also the teeny fraction of the available energy. What you're presupposing is that the means for using either is restricted to something like 19th or 20th century means.

Given enough energy or enough knowledge it is easy to extract fresh resources to top up the massive stockpile of used atoms of every type that we already have.

Given even moderate amounts of surplus energy it is always cheaper to recycle than it is to mine at the current concentrations of raw ore being mined.

The only reason that we don't currently do more on recycling is that it'd be pointless when the existing stockpile of minerals is already in use. We have an expanding population and an expanding infrastructure.

The only reason that we had to mine over the last 300 years is and has been the breakneck increase in human populations. Plus a steady rise of affluence amongst some parts of it over the last millennium. This was the breathless and rather idiotic view in 2011.

If you ever care to look at the demographics stats, then that is clearly not going to be a factor in future. We're going to add about just 2.5 billion to the existing 8 billion over the next 80 years up to 2100. We won't be adding a billion every decade as we have been doing through most of my life.

When I was born in 1959 when the world population was estimated at about 3 billion. That means that we have nearly tripled the world population while I have been alive. We have way more than tripled the worlds infrastructure.

We've been mining because that that was the only way to add the new resources to simultaneously provide the same things to new generations that our parents had in 1959 AND raise the level of resources at the same time for all living generations.

95% of the materials for roads, rail, airports, housing, comms lines, factories, stores, cars, trains, aircraft etc now present were not in a useable form in 1959. It has all been mined or extracted since then. Recycling has always gone on. It just wasn't sufficient to keep up with demand.

But that is slowly going to peter out as the rate of population growth decreases again and again. Sure there will be continued demand due to rising affluence and there will be mining to support that. But even that will fade out. Given sufficient energy it is always cheaper to recycle the concentrations of materials in unused infrastructure that it is mine.

That is why China as a country going through a massive infrastructure upgrade takes much of the infrastructural waste from the US and the EU to recycle. This isn't a new trend. Japan was doing that when I was born.

The only question in my mind over past decades was if we'd have the surplus energy to really start to recycle. That has been answered over the past decade. Renewables can easily supply the energy – you only have to look at South Austraila (surplus solar) or the North sea to see that.

There are still questions about the energy storage, buffering, and grid transport. But most of those are in the engineering refinement stage rather than the "is it possible" stage.

A meaningless way to express it because there is no comparable base of comparison. That is the David Farrar technique of how to lie meaninglessly with unrelated statistics. It is how you produce a slogan for the lazy and mindless to understand.

The more useful basal way of expressing it with population at its base…

NZ produces enough aluminium for 0.005 * 8 billion = 40 million people. It expends the electrical power for 0.13 * 5.1 million = 663,000 people to do it. That makes it look a whole lot different eh?

It is still a bullshit stat. It just happens to be more rational than your silly slogan

What is remarkable is how successful developed and major developing economies are in energy efficiency, and how fast.

The Top 10 Most Energy Efficient Countries | Quick Electricity

In order of appearance: France, UK, Germany and Netherlands tied, Italy, Spain, Japan, Taiwan, China, and the USA are the most efficient economies in energy use.

This is of course not the same as the countries leading the way in energy transition, which are the Usual Suspects from Scandinavia.

These countries are leading the energy transition race | World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

In 2022 the global economy used energy 2% more efficiently than it did in 2021, a rate of improvement almost four times that of the last two years, and almost double the rate of the past five years.

Poverty is rapidly decreasing across the world, with more than a billion fewer people living below the International Poverty Line of $2.15 per day than in 1990.

It is really, really tiring listening to Heinberg doing yet more Malthusian bullshit and he needs to stop, and it would be great if this bullshit weren't repeated here.

Whenever a politician starts talking about growth it is usually one from ACT or National.

And the growth they are talking about is their own bank balance.

That's all they ever care about, despite what they might claim otherwise.

That is a patently false statement….all political parties lionise 'growth' even the Greens.

Unfortunately growth is considered the measure of success…and not without reason….our entire system of being currently depends upon it.

Hmmm …

https://www.greens.org.nz/climate_change_policy

snap. Nice one, that one hadn't sunk in before now.

Hmmm indeed..

https://assets.nationbuilder.com/beachheroes/pages/9646/attachments/original/1596420974/policy-Greens_Economic.pdf?1596420974

More hmmm …

Doesn’t look like they are lionising ‘growth’, does it?

investment = growth …econ101

differentiation = growth …biol101

differentiation = growth …psych101

You forgot time….time is a bugger eh

Missing the point, several points, in fact.

Anywho, time is factored in all those growth processes, in fact it is a necessary factor. As with economic growth. And they all require investment of resources and some transformative step(s) (HT to Gosman).

Think like a Greenie, for a minute and think of the 4 pillars of the Green Party, none of which fits your econ101 label well.

Unfortunately Incognito the 4 pillars fit econ 101 all too well which if you are honest you will recognise.

As said to weka it is not a criticism, rather a statement of fact.

The problem for all politcal parties (and their voters) is a viable (acceptable?) pathway from here to there.

Sadly I see none….hence your labelling me as a fatalist.

I don’t see how. Econ 101 is fundamentally incompatible with both “This world is finite, therefore unlimited material growth is impossible” and “Ecological sustainability is paramount”.

The Greens have a set of principles, and they engage in policy making. They are willing to compromise on policy but not principles. The charter doesn’t say ‘hey, let’s do sustainability within neocapitalism and ignore nature’. That’s parliament saying that.

Nope, it is your interpretation, which doesn’t make it a fact, but your PoV through your chosen monocular lens of econ101 and all that comprises.

I don’t need to label, just making an observation that the shoe fits rather nicely and you wear it well.

The problem is that many commenters, even here on TS, appear to misunderstand the Green way of thinking (and acting) – it is not quite cookie-cutter mainstream politics and can be confusing for those who are less receptive to nuance. They mischaracterise and misrepresent Green policies by ‘green-splaining’ them through their own reductionist and often binary lens. This inevitably leads to twisting and contorting and thus to wrong conclusions accusing Greens of flawed logic, contradictions, and falsehoods. It almost never seems to occur to such people that they may be in fact incorrect in many of their assumptions and interpretations. This is a fact but since I’m addressing you, it’s a criticism too.

Not all growth is unsustainable …green101

if you accept that the world is finite then the very act of compromise is contrary to their principles.

Again it is not a criticism (or perhaps it is) but the fact remains…if you believe that growth is unsustainable, then you cannot (or should not) promote a misnomer, sustainable growth.

but I understand the logic for doing so, even if I see the falsehood.

Pat, by your argument, no political party who has the vision, ethics, and policies to make the necessary changes would ever be in parliament because they would have to compromise their core principles to do so. This would go some way to explaining why you believe that the necessary change won’t happen.

It’s like saying that climate activists have compromised their principles by driving a car, and therefore aren’t committed to climate change.

Meanwhile, the Greens can have the core principles in their Charter, and still work within the pragmatics of the system. Some people believe this means they have sold out, they don’t believe in the charter and are instead pro-growth and that they won’t lead on degrowth or steady state because of that compromise. But as Incognito is saying, such views come from not understanding how the GP works.

They are playing the long game. If they want to influence mainstream politics they have to work within mainstream structures, and they are the ones who change the mainstream by holding to their principles at the same time. This is how change happens.

lol…whatever gets you through the day

As you were …

@ weka

its like saying…exactly like…that if we wish to solve the problems created by growth we have to implement actions that nobody wants.

That may be a controversial statement but it dosnt necessarily make it incorrect.

Al Bartlett had a great list of the things we all considered ‘goods’ that potentially worked against the collective best interest…it is an enlightening list

Bartlett was a physicist and defined growth in a strictly physical quantitative way, as you do too and many an economist. When the Green Party writes “grow the value of exports”, for example, this doesn’t necessarily mean increase the volume but the quality. A so-called knowledge economy can have a light carbon footprint and still be better off than one that specialises (!) in producing and exporting bulk quantities of primary products. It takes imagination and courage to envision a different way of doing things and it only takes a little of negativity and resistance to keep on the garden path.

As long as you don’t want to consider this possibility, we’re doomed to talk past each other. As you were.

This is a political and philosophical positioning of yours, it’s not a fact.

For instance, there are increasing numbers of people who support alternative economic models, degrowth, steady state, doughnut and so on.

There are also many people working on Transition networks, or regenag or any number of transition techs.

Maybe it’s you that doesn’t want the actions that are necessary.

Nevertheless, the Greens are in parliament and they still have their core principles which address the problems of overpopulation, overconsumption, and the current economic model of perpetual growth.

And as long as you decline to accept that there is a relationship between the quantity of people and the consumption of resources and erosion of other (no matter the 'value') then you will continue to delude yourself that there are solutions that dont require less

As you are

More people need to consume more to meet the basic life necessities – never declined this, so it is a strawman. Beyond that, it becomes a debate about what is justified over-consumption and what is sustainable. Arguably, even without any increase in the number of people on the planet our collective way of living is unsustainable. If you cannot accept this then any talk about future predictions or models is moot beyond the pale.

Strawmen are not the problem

We are victims of our own success.

"Arguably, even without any increase in the number of people on the planet our collective way of living is unsustainable."

The evidence shows that to be the case…and yet all our current systems (detrimental as they are) are necessary to maintain that.

If you believe you have solved the moral dilemma presented by the 'overcrowded lifeboat' dont be shy and enlighten the world…there may be a Nobel prize in it for you.

I tried walking on water to rescue the strawmen in the Titanic hoping for a major reward that would make me feel

specialgreat, but alas … it was but a figment of your imagination. Those are like an iceberg.Maybe it is me ….but you yourself wrote "Meanwhile, the Greens can have the core principles in their Charter, and still work within the pragmatics of the system. Some people believe this means they have sold out, they don’t believe in the charter and are instead pro-growth and that they won’t lead on degrowth or steady state because of that compromise"

Now the Greens in NZ attract around 10% support from those that vote, and by your statement 'some' of the Greens think thats a sell out position but ipso facto the majority do not, or party policy would reflect that…so if its 'my' philosophy it is a philosophy supported by the overwhelming majority of voters…and that is a fact.

Your statement that some of the Greens think the GP being pragmatic and staying in parliament is a sell out is a reflection of your own purity politics, doesn’t really have much bearing on the GP’s principles or being willing to compromise on policy.

Your philosophy isn’t supported by the overwhelming majority of voters. People vote for a wide range of reasons and most people won’t even know what your philosophy is.

You believe that no-one wants to make the necessary change. I can easily point to individuals and whole movements that demonstrate this is simply not true. I write whole posts about this. The vast majority of NZ voters don’t know what the alternatives are or at least don’t see them as possible. The argument here is about why, and people saying ‘we can’t change’ or ‘no-one wants to change’ is part of the problem.

Research shows most people in NZ want more action on climate. There are obviously forces working against that, but that’s a different thing from saying no-one is willing to change. Lots of people are waiting for change and wanting it to happen.

In your opinion.

pat wrote:

"if you believe that growth is unsustainable, then you cannot (or should not) promote a misnomer, sustainable growth."

Forests grow…sustainably.

The biosphere seemed, until humans emerged, to be growing sustainably.

Growth, moderated/governed/regulated by natural death and decay, is sustainable (not infinitely, perhaps, but long-term enough to need a fair stack of fire-fighter's calendars to cover).

and that is the antithesis of the global economy’s obsession with perpetual growth. I wish we could just get to the conversation about how we can think like a forest in order to meet human needs, instead of chopping all the trees down.

Weka wrote:

"I wish we could just get to the conversation about how we can think like a forest in order to meet human needs, instead of chopping all the trees down."

Same. I have ideas about this. Goethe had ideas about this. Thinking like a forest is doable. Trying to do so, using the frameworks we use to build our towns and cities, transport ourselves around etc. will hamper the needed dialogue. We first have to unravel the tangled skein of habit, expectation, faith and desire we have woven for ourselves. That's harder, few can do it. Meeting our needs in a "forest-friendly" way is doable. We just need to take advice

The Greens will shift to degrowth or steady state narratives when it becomes politically possible to do so. I would guess TPM will too.

From the GP charter,

https://www.greens.org.nz/charter

Point being, it's hardwired into the charter for a reason, and many in the Greens would make the change now if it were possible.

Yes some would shift to degrowth now if as you say it were politically viable…but the fact remains the party policy retains a growth agenda (albeit with a sustainable rider)…it is not a criticism, merely a statement of fact.

That's different from lionising. They're a mainstream political party. They have to work within a parliament and government that runs a neoliberal economy. It's pragmatics.

Yes it is mainstream…and the mainstream lionise growth.

as said…not without reason.

"fact" ?

You can identify and verify "fact"?

You the man!

Are you sure your name isnt Richard rather than Robert?

Richardratherthanrobert is a very uncommon name in these parts, pat.

Robert, I be.

You?

"This world is finite"

Is it?

How so??

the bit in the post about the planet not expanding along with humans extracting resources is probably as good a response as any.

It isn’t a patently false statement at all.

How often do you hear National or ACT talking about “managing” resources the way the Greens or (sometimes) Labour do?

Almost never.

They exist on the premise that everyone should want more and more of everything and one should never be satisfied with what one has.

Our planet cannot sustain the “more…more” philosophy much longer but National and ACT are blind and deaf to this.

Correct!

It's all about story.

Guard yourself against story-tellers who's stories are truncated.

except for the elephant in the living room's story.

Has anyone got a counter to concern about the need to bury somewhat toxic windmill turbines and solar panels after their use?

The Oz coal industry shills are onto the issue as a way to place pressure on their new government.

https://www.indystar.com/story/news/environment/2021/03/23/how-to-keep-solar-panels-and-wind-turbines-out-landfills/6875966002/

Given this plant is by it's very nature exposed to the weather, or worse the ocean, the expected life can be reasonably expected to be in the range of 10 to 25 years. And that is being generous.

The article you link to looks reasonable to me. The correct answer is recycling, but ideally this has to be incorporated into the design right from the outset in order to be efficient. As far as I am aware, none of our current SWB designs take this into account, nor are there any published lifecycle plans around disposal.

I was talking with a project engineer a month or two back (in a very different context) bemoaning how difficult it was to scale up the pilot plant he was working on. Issues, problems and waste streams that are easily dealt with at small scale, quickly become monsters as you go big.

I'm amazed that this Malthusian nonsense has raised its head once more. A forecast of the global human population reaching 18 billion this century?

I had similar arguments on Kiwiblog in 2008 where I quoted another book published in 1974, not long after The Population Bomb and at the same time as a number of doom-mongering tomes. The book was called The Next Ten Thousand Years and it was written by a guy who specialised in popularising science and technology. His name was Adrian Berry and he freely admitted that trying to predict how humanity would develop over such an enormous span of time was very speculative. But he thought it would be fun and interesting if he could ground it in known science as far as possible.

Before he pushed forward in time though he felt he had to give a brief background as to the development of science and technology to date and focusing on the philosophies behind it. He also felt he had to deal with the various predictions of doom that were then in vogue, including Mr Erlich and friends (of the Earth). With regard to the population explosion predictions this is a little of what he wrote:

A set of rational, logically connected arguments grounded in a degree of understanding of human nature that Erlich and company never came close to grasping. Moreover, arguments and predictions that turned out to be right. Not bad for one page from a relatively obscure author with probably no more than a humble Bachelors degree to his name, if that. Something to remember the next time somebody tries to browbeat one into not speaking up against experts with superior qualifications and knowledge.