Parihaka

Parihaka

Written By:

mickysavage - Date published:

11:09 am, December 30th, 2020 - 8 comments

Categories: history, Maori Issues, racism, uncategorized -

Tags:

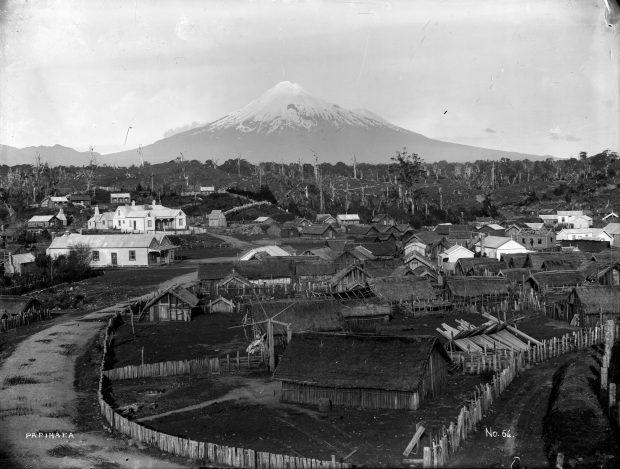

I am spending some time down in Taranaki and thought I would check out some of the local historical sites.

Top of my list was Parihaka.

I was generally aware of its history but after reading some more about it I cannot believe how badly local iwi were treated, and how this particular treaty settlement was, out of a crowded field, so just.

A starting point is the Treaty of Wairangi, especially article 2 which said:

The Queen of England agrees and consents (to Give) to the Chiefs, hapus, and all the people of New Zealand, the full chieftainship (rangatiratanga) of their lands, their villages and all their possessions (taonga: everything that is held precious) but the Chiefs give to the Queen the purchasing of those pieces of land which the owner is willing to sell, subject to the arranging of payment which will be agreed to by them and the purchaser who will be appointed by the Queen for the purpose of buying for her.

This did not last long. The land wars, essentially a grab of land by the authorities and pakeha immigrants erupted. One of the causes, the Waitara purchase, caused fighting to break out in Taranaki.

The New Zealand History website has this description of how it started:

The opening shots of the first Taranaki War were fired when British troops attacked a pā built by Te Āti Awa chief Te Rangitāke at Te Kohia, Waitara.

A minor chief, Te Teira Mānuka, had offered to sell Governor Thomas Gore Browne land in 1859. Te Rangitāke (also known as Wiremu Kīngi) denied the validity of the sale and his supporters erected a flagstaff to mark their boundary.

Gore Browne overturned previous policy by pursuing a contested land sale. He hoped to win support from New Plymouth settlers desperate for land. When Gore Browne ordered surveyors onto the Pekapeka block, Māori pulled up their pegs. The governor declared martial law and sent in British troops.

This sort of event, sale of land by an individual clearly without tribal authority that the European authorities then insisted on enforcing, happened time and time again during our country’s history.

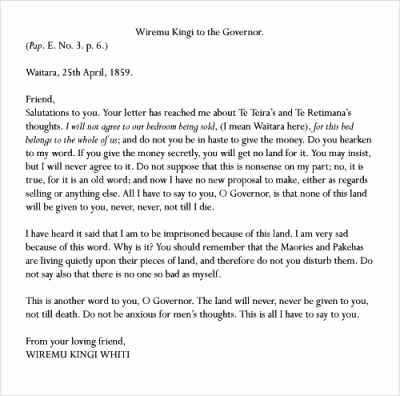

The actutal chief, Wiremu Kingi had previously tried the polite response and wrote to Governor Thomas Gore Browne. In legal terms Browne was being put on notice:

Browne did not take the hint.

The fighting itself ended more in a stalemate than a victory for the settlers with Kingi and his supporters proving to be adept at the use of fortifications protecting them against the overwhelming firepower the authorities utilised.

The settler dominated Parliament then chose to pass the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 which allowed the confiscation (raupatu) of land owned by any tribes deemed to be in open rebellion with the Crown. All of Taranaki was deemed to be in open rebellion, ergo they all lost their land. Clearly as far as the settlers were concerned the opposition to clearly unenforceable contracts for the sale of land was tantamount to rebellion. And while for the purposes of land sales individual Maori had the right to do what they wanted when it came time to land confiscation under the Act all Maori were collectively responsible for the actions of a few.

The Taranaki Iwi website has this description of the confiscation process:

The New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863 provided for the confiscation of Maori land when the Crown determined an iwi, or a significant number of members of an iwi, had been in rebellion against the Queen.

On 31 January 1865 “Middle Taranaki” was declared a confiscation district. The area commenced at the Waitara River mouth and extended to the Waimate Stream in the south, within which eligible sites were to be taken for military settlement. Oākura and Waitara South were then declared as “eligible sites for settlement for colonisation” being specific areas within the wider ‘Middle Taranaki’ district. In September of that year two other districts were declared, Ngatiawa and Ngatiruanui. The Ngati Ruanui and Middle Taranaki districts included the entire Taranaki Iwi rohe and the Crown assumed ownership of all the land within that district.

A Compensation Court set up under the New Zealand Settlements Act was intended to return land to some of those affected by the confiscations, principally those who were deemed not in rebellion against the Crown. Every member of Taranaki Iwi who sought the return of their land was required to do so through the Compensation Court. Those deemed rebels could not make claims.

In 1866, the Court made 147 awards totalling 20,400 acres for the whole of the Taranaki area. The awards were made via land scrip and promissory pieces of paper to individuals (and mostly settled out of court) rather than iwi, the customary way in which we had held title to our lands.

Against this background Te Whiti and Tohu decided to set up a new community at Parihaka. It was pan tribal and at its peak 2,500 people lived there. They also decided on the unusual but logically compelling tactic of engaging in completely peaceful opposition to attempts to take from them their whenua. Surely if they did not fight the European settlers they could not be deemed to be in rebellion against the Crown?

Unfortunately not. The greed for land clearly usurped considerations such as the rule of law and the provisions of the Treaty.

The actions taken by local iwi would have made Mahatma Ghandi proud. The treaty settlement summary has this description of the steps they took:

In May 1879, followers of Te Whiti and Tohu began to plough land across Taranaki, as an assertion of their rights to the land. By the end of July, 182 ploughmen had been arrested. Only 46 received a trial, but all were detained in harsh conditions in South Island prisons for at least 14 months, and some for two years. In June 1880, Crown forces began to construct a road through cultivations near Parihaka. Between July and September 1880, 223 more Māori were arrested for placing fences across the road in an attempt to protect the cultivations. Only 59 fencers received a trial, but again all were sent to South Island prisons. Over this period, the Crown promoted and passed legislation to enable the continuing detention of those prisoners who had not been tried.

In July 1881, people from Parihaka and surrounding Taranaki Iwi settlements erected fences around traditional cultivation sites which the Crown had sold to settlers. On 5 November 1881, more than 1500 Crown troops, led by the Native Minister, invaded Parihaka and then dismantled the settlement and forcibly removed many of its inhabitants. Te Whiti and Tohu were arrested and held without trial for 16 months.

For their efforts Te Whiti and Tohu were put on trial but something unusual happened. They struck a fair Judge. Dick Scott in his book on Parihaka describes what happened:

After six months behind bars Titokowaru came before Judge Gillies in the supreme court, New Plymouth. The judge dropped a bombshell. Questioning the legality of the whole Parihaka expedition, he declared no cabinet minister could personally conduct such a campaign ‘of his own mere will’; he must act under formal and official authority. If the jury found Bryce and Hursthouse had not been properly authorised to disperse people who ‘merely sat still’, their duty was to bring in a no bill.

The grand jury found true bills and the newspapers headed an attack on the judge for his remarks. But Gillies, a judge of unusual character, had a record of independent rulings. On 8 May when the case came for trial, Whitaker, the new Prime Minister (Hall had retired with a knighthood), ordered the crown prosecutor to drop the prosecution. After men had been imprisoned on grave charges for a long time it was ‘a very extraordinary proceeding,’ Judge Gillies commented, ‘more especially when I see that two of the indictments have been quashed on account of insufficiency in the face of them.’ Addressing the dock he said: ‘The government has determined not to bring you to be tried on this charge. You have already been in prison six months waiting for trial. Nor does the government offer any evidence. You are therefore free to go where you will.’

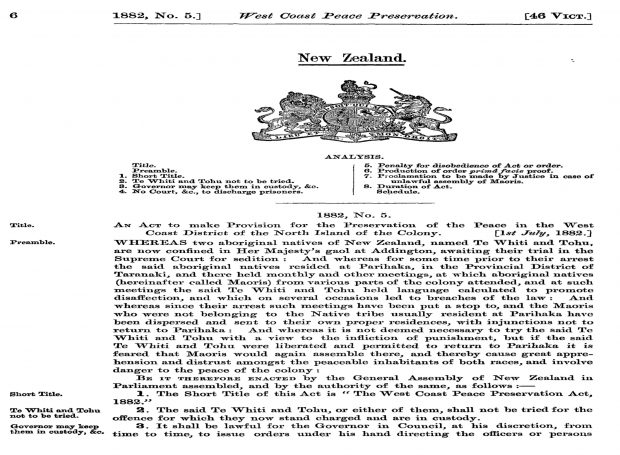

The Government responded by passing the most extreme, obscene overreach of law I have ever seen. The effect was to allow the continued detention of Te Whiti and Tohu without trial and to protect those who had clearly acted illegally in arresting and detaining them.

As for the promise to reserve some land as reservations this was also broken. Again from the Treaty Settlement summary:

In 1881, the West Coast Commission found that the Crown had failed to fulfill promises about Māori reserves, and recommended that some reserves be granted. However, reserves were not returned to Māori outright, but were placed under the administration of the Public Trustee, who then sold or leased in perpetuity large areas to European farmers. Through the 20th century, a number of legislative acts further undermined the ability of Taranaki Iwi people to retain or control their remaining lands. Today, less than 5 percent of the reserved lands are in Māori freehold ownership, and approximately 50,000 acres remain leased in perpetuity. The massive loss of land has limited the ability of Taranaki Iwi to participate in society on equal terms with many other New Zealanders.

Recently the Crown has been seeking to repair the damage and make amends for what occurred. The Taranaki Iwi Deed of settlement summary contained this apology:

The deed of settlement contains acknowledgements that historical Crown actions or omissions caused prejudice to Taranaki Iwi or breached the Treaty of Waitangi and its principles.

The deed of settlement also includes a Crown apology to Taranaki Iwi for its acts and omissions which breached the Crown’s obligations under the Treaty of Waitangi and for the damage that those actions caused to Taranaki Iwi. These include the Crown’s actions that led to the outbreak of war in Taranaki, the indiscriminate, unjust and unconscionable confiscation of the land that had supported Taranaki Iwi for centuries, and its invasion of Parihaka and systematic dismantling of the community.

Financial redress totalling $74 million were made. Ignoring the social and economic loss suffered by local iwi the payment represents $3,600 per acre of land which the authorities had promised to return. This is absolute peanuts.

Parihaka had its own special piece of legislation, Te Ture Haeata ki Parihaka 2019. At the introduction of the Bill Kelvin Davis said this:

This bill is the result of a long journey. In 2014, Taranaki iwi, Parihaka, and the Crown agreed to establish a working group aptly named Kawe Tutaki, which means “a vehicle towards closure”. Kawe Tutaki advised Ministers on how the Crown could best support the Parihaka community outside the Treaty settlement process. After careful consultation with the Parihaka community, Ministers, Crown agencies, and local authorities, Kawe Tutaki recommended the Crown reconcile its troubled relationship with Parihaka and recognise the community’s important legacy, and assist Parihaka to again become a vibrant and sustainable community founded on principles established by its visionary leaders Tohu Kākahi and Te Whiti o Rongomai.

A compact of trust was signed on 22 May 2016 as a first step to rebuild the relationship. In November that year, the Crown proposed a reconciliation package that included formal relationship agreements with Government agencies and local bodies, a financial contribution towards Parihaka’s future development, a Parihaka-Crown relationship forum, and a formal apology from the Crown. The Parihaka Papakāinga Trust then led an innovative consultation process with the community to decide whether the package was acceptable.

I acknowledge the decision was not an easy one, and that, in ultimately deciding to accept this package, the people of Parihaka have chosen to look towards the future. On 9 June 2017, a reconciliation ceremony took place at Parihaka where the Crown and Parihaka signed Te Kawenata ō Rongo, the deed of reconciliation, which records the elements of the reconciliation package. The reconciliation ceremony was not only an important turning point in the relationship between the Crown and the people of Parihaka but a day of national significance.

Reading through the documents I am struck by a few things, how egregious Taranaki Iwi were treated, how their rights were trampled on, how possibly the first attempt at a non violent response to tyranny was met with further tyranny, and how the treaty settlement is but a very modest compensation package for what local iwi has suffered.

Related Posts

8 comments on “Parihaka ”

- Comments are now closed

- Comments are now closed

Recent Comments

- SPC to Phillip ure on

- Traveller to Phillip ure on

- SPC to Mike the Lefty on

- Ad to Phillip ure on

- Anne to Mike the Lefty on

- adam to Phillip ure on

- adam on

- Phillip ure to adam on

- Phillip ure to Traveller on

- adam to Phillip ure on

- Phillip ure on

- adam on

- Traveller to Drowsy M. Kram on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Traveller on

- Traveller to Drowsy M. Kram on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Traveller on

- Traveller on

- aj on

- weston on

- SPC to Phillip ure on

- Rodel on

- Phillip ure to SPC on

- Phillip ure on

- Phillip ure to lprent on

- SPC on

- lprent to Phillip ure on

- Phillip ure on

- Phillip ure on

- Gristle on

- Ad on

Recent Posts

-

by mickysavage

-

by advantage

-

by advantage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by Guest post

-

by advantage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by advantage

-

by weka

-

by nickkelly

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Guest post

- Fact Brief – Is Antarctica gaining land ice?

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park in collaboration with members from our Skeptical Science team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Is Antarctica gaining land ice? ...11 hours ago

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park in collaboration with members from our Skeptical Science team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Is Antarctica gaining land ice? ...11 hours ago - Policing protests.

Images of US students (and others) protesting and setting up tent cities on US university campuses have been broadcast world wide and clearly demonstrate the growing rifts in US society caused by US policy toward Israel and Israel’s prosecution of … Continue reading → ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo17 hours ago

Images of US students (and others) protesting and setting up tent cities on US university campuses have been broadcast world wide and clearly demonstrate the growing rifts in US society caused by US policy toward Israel and Israel’s prosecution of … Continue reading → ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo17 hours ago - Open letter to Hon Paul Goldsmith

Barrie Saunders writes – Dear Paul As the new Minister of Media and Communications, you will be inundated with heaps of free advice and special pleading, all in the national interest of course. For what it’s worth here is my assessment: Traditional broadcasting free to air content through ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544317 hours ago

Barrie Saunders writes – Dear Paul As the new Minister of Media and Communications, you will be inundated with heaps of free advice and special pleading, all in the national interest of course. For what it’s worth here is my assessment: Traditional broadcasting free to air content through ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544317 hours ago - Bryce Edwards: FastTrackWatch – The Case for the Government’s Fast Track Bill

Many criticisms are being made of the Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill, including by this writer. But as with everything in politics, every story has two sides, and both deserve attention. It’s important to understand what the Government is trying to achieve and its arguments for such a bold reform. ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards17 hours ago

Many criticisms are being made of the Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill, including by this writer. But as with everything in politics, every story has two sides, and both deserve attention. It’s important to understand what the Government is trying to achieve and its arguments for such a bold reform. ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards17 hours ago - Luxon gets out his butcher’s knife – briefly

Peter Dunne writes – The great nineteenth British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, once observed that “the first essential for a Prime Minister is to be a good butcher.” When a later British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, sacked a third of his Cabinet in July 1962, in what became ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544318 hours ago

Peter Dunne writes – The great nineteenth British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, once observed that “the first essential for a Prime Minister is to be a good butcher.” When a later British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, sacked a third of his Cabinet in July 1962, in what became ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544318 hours ago - More tax for less

Ele Ludemann writes – New Zealanders had the OECD’s second highest tax increase last year: New Zealanders faced the second-biggest tax raises in the developed world last year, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) says. The intergovernmental agency said the average change in personal income tax ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544319 hours ago

Ele Ludemann writes – New Zealanders had the OECD’s second highest tax increase last year: New Zealanders faced the second-biggest tax raises in the developed world last year, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) says. The intergovernmental agency said the average change in personal income tax ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544319 hours ago - Real News vs Fake News.

We all know something’s not right with our elections. The spread of misinformation, people being targeted with soundbites and emotional triggers that ignore the facts, even the truth, and influence their votes.The use of technology to produce deep fakes. How can you tell if something is real or not? Can ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel22 hours ago

We all know something’s not right with our elections. The spread of misinformation, people being targeted with soundbites and emotional triggers that ignore the facts, even the truth, and influence their votes.The use of technology to produce deep fakes. How can you tell if something is real or not? Can ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel22 hours ago - Another way to roll

Hello! Here comes the Saturday edition of More Than A Feilding, catching you up on the past week’s editions.Share ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack23 hours ago

Hello! Here comes the Saturday edition of More Than A Feilding, catching you up on the past week’s editions.Share ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack23 hours ago - Simon Clark: The climate lies you'll hear this year

This video includes conclusions of the creator climate scientist Dr. Simon Clark. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any). This year you will be lied to! Simon Clark helps prebunk some misleading statements you'll hear about climate. The video includes ...1 day ago

This video includes conclusions of the creator climate scientist Dr. Simon Clark. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any). This year you will be lied to! Simon Clark helps prebunk some misleading statements you'll hear about climate. The video includes ...1 day ago - Cutting the Public Service

It is all very well cutting the backrooms of public agencies but it may compromise the frontlines. One of the frustrations of the Productivity Commission’s 2017 review of universities is that while it observed that their non-academic staff were increasing faster than their academic staff, it did not bother to ...PunditBy Brian Easton2 days ago

It is all very well cutting the backrooms of public agencies but it may compromise the frontlines. One of the frustrations of the Productivity Commission’s 2017 review of universities is that while it observed that their non-academic staff were increasing faster than their academic staff, it did not bother to ...PunditBy Brian Easton2 days ago - Luxon’s demoted ministers might take comfort from the British politician who bounced back after th...

Buzz from the Beehive Two speeches delivered by Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters at Anzac Day ceremonies in Turkey are the only new posts on the government’s official website since the PM announced his Cabinet shake-up. In one of the speeches, Peters stated the obvious: we live in a troubled ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin2 days ago

Buzz from the Beehive Two speeches delivered by Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters at Anzac Day ceremonies in Turkey are the only new posts on the government’s official website since the PM announced his Cabinet shake-up. In one of the speeches, Peters stated the obvious: we live in a troubled ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin2 days ago - This is how I roll over

1. Which of these would you not expect to read in The Waikato Invader?a. Luxon is here to do business, don’t you worry about thatb. Mr KPI expects results, and you better believe itc. This decisive man of action is getting me all hot and excitedd. Melissa Lee is how ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago

1. Which of these would you not expect to read in The Waikato Invader?a. Luxon is here to do business, don’t you worry about thatb. Mr KPI expects results, and you better believe itc. This decisive man of action is getting me all hot and excitedd. Melissa Lee is how ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago - The Waitangi Tribunal is not “a roving Commission”…

…it has a restricted jurisdiction which must not be abused: it is not an inquisition NOTE – this article was published before the High Court ruled that Karen Chhour does not have to appear before the Waitangi Tribunal Gary Judd writes – The High Court ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago

…it has a restricted jurisdiction which must not be abused: it is not an inquisition NOTE – this article was published before the High Court ruled that Karen Chhour does not have to appear before the Waitangi Tribunal Gary Judd writes – The High Court ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago - Is Oranga Tamariki guilty of neglect?

Lindsay Mitchell writes – One of reasons Oranga Tamariki exists is to prevent child neglect. But could the organisation itself be guilty of the same? Oranga Tamariki’s statistics show a decrease in the number and age of children in care. “There are less children ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin2 days ago

Lindsay Mitchell writes – One of reasons Oranga Tamariki exists is to prevent child neglect. But could the organisation itself be guilty of the same? Oranga Tamariki’s statistics show a decrease in the number and age of children in care. “There are less children ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin2 days ago - Three Strikes saw lower reoffending

David Farrar writes: Graeme Edgeler wrote in 2017: In the first five years after three strikes came into effect 5248 offenders received a ‘first strike’ (that is, a “stage-1 conviction” under the three strikes sentencing regime), and 68 offenders received a ‘second strike’. In the five years prior to ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago

David Farrar writes: Graeme Edgeler wrote in 2017: In the first five years after three strikes came into effect 5248 offenders received a ‘first strike’ (that is, a “stage-1 conviction” under the three strikes sentencing regime), and 68 offenders received a ‘second strike’. In the five years prior to ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago - Luxon’s ruthless show of strength is perfect for our angry era

Bryce Edwards writes – Prime Minister Christopher Luxon has surprised everyone with his ruthlessness in sacking two of his ministers from their crucial portfolios. Removing ministers for poor performance after only five months in the job just doesn’t normally happen in politics. That’s refreshing and will be extremely ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago

Bryce Edwards writes – Prime Minister Christopher Luxon has surprised everyone with his ruthlessness in sacking two of his ministers from their crucial portfolios. Removing ministers for poor performance after only five months in the job just doesn’t normally happen in politics. That’s refreshing and will be extremely ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago - 'Lacks attention to detail and is creating double-standards.'

TL;DR: These are the six things that stood out to me in news and commentary on Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy in the two days to 6:06am on Thursday, April 25:Politics: PM Christopher Luxon has set up a dual standard for ministerial competence by demoting two National Cabinet ministers while leaving also-struggling ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

TL;DR: These are the six things that stood out to me in news and commentary on Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy in the two days to 6:06am on Thursday, April 25:Politics: PM Christopher Luxon has set up a dual standard for ministerial competence by demoting two National Cabinet ministers while leaving also-struggling ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - One Night Only!Hi,Today I mainly want to share some of your thoughts about the recent piece I wrote about success and failure, and the forces that seemingly guide our lives. But first, a quick bit of housekeeping: I am doing a Webworm popup in Los Angeles on Saturday May 11 at 2pm. ...David FarrierBy David Farrier2 days ago

- What did Melissa Lee do?

It is hard to see what Melissa Lee might have done to “save” the media. National went into the election with no public media policy and appears not to have developed one subsequently. Lee claimed that she had prepared a policy paper before the election but it had been decided ...PolitikBy Richard Harman2 days ago

It is hard to see what Melissa Lee might have done to “save” the media. National went into the election with no public media policy and appears not to have developed one subsequently. Lee claimed that she had prepared a policy paper before the election but it had been decided ...PolitikBy Richard Harman2 days ago - Skeptical Science New Research for Week #17 2024

Open access notables Ice acceleration and rotation in the Greenland Ice Sheet interior in recent decades, Løkkegaard et al., Communications Earth & Environment: In the past two decades, mass loss from the Greenland ice sheet has accelerated, partly due to the speedup of glaciers. However, uncertainty in speed derived from satellite products ...2 days ago

Open access notables Ice acceleration and rotation in the Greenland Ice Sheet interior in recent decades, Løkkegaard et al., Communications Earth & Environment: In the past two decades, mass loss from the Greenland ice sheet has accelerated, partly due to the speedup of glaciers. However, uncertainty in speed derived from satellite products ...2 days ago - Maori Party (with “disgust”) draws attention to Chhour’s race after the High Court rules on Wa...

Buzz from the Beehive A statement from Children’s Minister Karen Chhour – yet to be posted on the Government’s official website – arrived in Point of Order’s email in-tray last night. It welcomes the High Court ruling on whether the Waitangi Tribunal can demand she appear before it. It does ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin3 days ago

Buzz from the Beehive A statement from Children’s Minister Karen Chhour – yet to be posted on the Government’s official website – arrived in Point of Order’s email in-tray last night. It welcomes the High Court ruling on whether the Waitangi Tribunal can demand she appear before it. It does ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin3 days ago - Who’s Going Up The Media Mountain?

Mr Bombastic: Ironically, the media the academic experts wanted is, in many ways, the media they got. In place of the tyrannical editors of yesteryear, advancing without fear or favour the interests of the ruling class; the New Zealand news media of today boasts a troop of enlightened journalists dedicated to ...3 days ago

Mr Bombastic: Ironically, the media the academic experts wanted is, in many ways, the media they got. In place of the tyrannical editors of yesteryear, advancing without fear or favour the interests of the ruling class; the New Zealand news media of today boasts a troop of enlightened journalists dedicated to ...3 days ago - “That's how I roll”

It's hard times try to make a livingYou wake up every morning in the unforgivingOut there somewhere in the cityThere's people living lives without mercy or pityI feel good, yeah I'm feeling fineI feel better then I have for the longest timeI think these pills have been good for meI ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago

It's hard times try to make a livingYou wake up every morning in the unforgivingOut there somewhere in the cityThere's people living lives without mercy or pityI feel good, yeah I'm feeling fineI feel better then I have for the longest timeI think these pills have been good for meI ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago - “Comity” versus the rule of law

In 1974, the US Supreme Court issued its decision in United States v. Nixon, finding that the President was not a King, but was subject to the law and was required to turn over the evidence of his wrongdoing to the courts. It was a landmark decision for the rule ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago

In 1974, the US Supreme Court issued its decision in United States v. Nixon, finding that the President was not a King, but was subject to the law and was required to turn over the evidence of his wrongdoing to the courts. It was a landmark decision for the rule ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago - Aotearoa: a live lab for failed Right-wing socio-economic zombie experiments once more…

Every day now just seems to bring in more fresh meat for the grinder. In their relentlessly ideological drive to cut back on the “excessive bloat” (as they see it) of the previous Labour-led government, on the mountains of evidence accumulated in such a short period of time do not ...exhALANtBy exhalantblog3 days ago

Every day now just seems to bring in more fresh meat for the grinder. In their relentlessly ideological drive to cut back on the “excessive bloat” (as they see it) of the previous Labour-led government, on the mountains of evidence accumulated in such a short period of time do not ...exhALANtBy exhalantblog3 days ago - Water is at the heart of farmers’ struggle to survive in Benin

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Megan Valére Sosou Market gardening site of the Itchèléré de Itagui agricultural cooperative in Dassa-Zoumè (Image credit: Megan Valère Sossou) For the residents of Dassa-Zoumè, a city in the West African country of Benin, choosing between drinking water and having enough ...3 days ago

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Megan Valére Sosou Market gardening site of the Itchèléré de Itagui agricultural cooperative in Dassa-Zoumè (Image credit: Megan Valère Sossou) For the residents of Dassa-Zoumè, a city in the West African country of Benin, choosing between drinking water and having enough ...3 days ago - At a time of media turmoil, Melissa had nothing to proclaim as Minister – and now she has been dem...

Buzz from the Beehive

Buzz from the Beehive Melissa Lee – as may be discerned from the screenshot above – has not been demoted for doing something seriously wrong as Minister of ... Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin4 days ago

Melissa Lee – as may be discerned from the screenshot above – has not been demoted for doing something seriously wrong as Minister of ... Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin4 days ago - These people are not our friends

Morning in London Mother hugs beloved daughter outside the converted shoe factory in which she is living.Afternoon in London Travelling writer takes himself and his wrist down to A&E, just to be sure. Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack4 days ago

Morning in London Mother hugs beloved daughter outside the converted shoe factory in which she is living.Afternoon in London Travelling writer takes himself and his wrist down to A&E, just to be sure. Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack4 days ago - Some advice from our tertiary history for the University Advisory Group

Mike Grimshaw writes – The recent announcement of the University Advisory Group, chaired by Sir Peter Gluckman, makes very clear where the Government’s focus and priorities lie. The remit of the Advisory Group is that Group members will consider challenges and opportunities for improvement in the university sector including: ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago

Mike Grimshaw writes – The recent announcement of the University Advisory Group, chaired by Sir Peter Gluckman, makes very clear where the Government’s focus and priorities lie. The remit of the Advisory Group is that Group members will consider challenges and opportunities for improvement in the university sector including: ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago - Still no prudential regulation case around climate change

Eric Crampton writes – The Reserve Bank of New Zealand desperately wants to find reasons to have workstreams in climate change. It makes little sense. They’ve run another stress test on the banks looking to see if they could find a prudential regulation case. They couldn’t. They ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago

Eric Crampton writes – The Reserve Bank of New Zealand desperately wants to find reasons to have workstreams in climate change. It makes little sense. They’ve run another stress test on the banks looking to see if they could find a prudential regulation case. They couldn’t. They ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago - Bernard’s pick ‘n’ mix of the news links for Wednesday, April 24

TL;DR: These six news links stood out to me in the last 24 hours or so onWednesday, April 23:Scoop: 'Released in error': Treasury paper hints at axing $6b flood resilience plan by NZ Herald-$$$ Thomas CoughlanScoop: EY launches new misconduct review amid Fonterra ban. Fonterra tells EY to remove some ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

TL;DR: These six news links stood out to me in the last 24 hours or so onWednesday, April 23:Scoop: 'Released in error': Treasury paper hints at axing $6b flood resilience plan by NZ Herald-$$$ Thomas CoughlanScoop: EY launches new misconduct review amid Fonterra ban. Fonterra tells EY to remove some ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - How National can neutralise serious allegations of corruption should the “Fast Track” Bill becom...

Rob MacCullough writes – Pundits from the left and the right are arguing that National’s Fast Track Bill that is designed to speed up infrastructure decisions could end up becoming mired in a cesspool of corruption. Political commentator ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago

Rob MacCullough writes – Pundits from the left and the right are arguing that National’s Fast Track Bill that is designed to speed up infrastructure decisions could end up becoming mired in a cesspool of corruption. Political commentator ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago - Cleaning Up After Gabrielle.

Looking at the headlines this morning it’s hard to feel anything other than pessimistic about the future of humanity.Note that I’m not speaking about the future of mankind, but the survival of our humanity. The values that we believe in seem to be ebbing away, by the day.Perhaps every generation ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago

Looking at the headlines this morning it’s hard to feel anything other than pessimistic about the future of humanity.Note that I’m not speaking about the future of mankind, but the survival of our humanity. The values that we believe in seem to be ebbing away, by the day.Perhaps every generation ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago - Gordon Campbell on bird flu, AUKUS entry fees and Cindy Lee

Swabbing mixed breed baby chicks to test for avian influenzaUh oh. Bird flu – often deadly to humans – is not only being transmitted from infected birds to dairy cows, but is now travelling between dairy cows. As of last Friday, Bloomberg News reports, there were 32 American dairy herds ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon4 days ago

Swabbing mixed breed baby chicks to test for avian influenzaUh oh. Bird flu – often deadly to humans – is not only being transmitted from infected birds to dairy cows, but is now travelling between dairy cows. As of last Friday, Bloomberg News reports, there were 32 American dairy herds ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon4 days ago - Tolling Existing Roads

One of the government’s transport policy and agreements with it’s coalition partners made it clear that they were looking at options like tolling and road pricing. This was reinforced in it’s draft Government Policy Statement released at the start of March which made a couple of references to it. Road pricing, ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L4 days ago

One of the government’s transport policy and agreements with it’s coalition partners made it clear that they were looking at options like tolling and road pricing. This was reinforced in it’s draft Government Policy Statement released at the start of March which made a couple of references to it. Road pricing, ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L4 days ago - At a glance – The difference between weather and climate

On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a ...5 days ago

On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a ...5 days ago - More criminal miners

What is it with the mining industry? Its not enough for them to pillage the earth - they apparently can't even be bothered getting resource consent to do so: The proponent behind a major mine near the Clutha River had already been undertaking activity in the area without a ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant5 days ago

What is it with the mining industry? Its not enough for them to pillage the earth - they apparently can't even be bothered getting resource consent to do so: The proponent behind a major mine near the Clutha River had already been undertaking activity in the area without a ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant5 days ago - Photos from the road

Photo # 1 I am a huge fan of Singapore’s approach to housing, as described here two years ago by copying and pasting from The ConversationWhat Singapore has that Australia does not is a public housing developer, the Housing Development Board, which puts new dwellings on public and reclaimed land, ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack5 days ago

Photo # 1 I am a huge fan of Singapore’s approach to housing, as described here two years ago by copying and pasting from The ConversationWhat Singapore has that Australia does not is a public housing developer, the Housing Development Board, which puts new dwellings on public and reclaimed land, ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack5 days ago - RMA reforms aim to ease stock-grazing rules and reduce farmers’ costs – but Taxpayers’ Union w...

Buzz from the Beehive Reactions to news of the government’s readiness to make urgent changes to “the resource management system” through a Bill to amend the Resource Management Act (RMA) suggest a balanced approach is being taken. The Taxpayers’ Union says the proposed changes don’t go far enough. Greenpeace says ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin5 days ago

Buzz from the Beehive Reactions to news of the government’s readiness to make urgent changes to “the resource management system” through a Bill to amend the Resource Management Act (RMA) suggest a balanced approach is being taken. The Taxpayers’ Union says the proposed changes don’t go far enough. Greenpeace says ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin5 days ago - Luxon Strikes Out.

I’m starting to wonder if Anna Burns-Francis might be the best political interviewer we’ve got. That might sound unlikely to you, it came as a bit of a surprise to me.Jack Tame can be excellent, but has some pretty average days. I like Rebecca Wright on Newshub, she asks good ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago

I’m starting to wonder if Anna Burns-Francis might be the best political interviewer we’ve got. That might sound unlikely to you, it came as a bit of a surprise to me.Jack Tame can be excellent, but has some pretty average days. I like Rebecca Wright on Newshub, she asks good ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago - In many ways the media that the experts wanted, turned out to be the media they have got

Chris Trotter writes – Willie Jackson is said to be planning a “media summit” to discuss “the state of the media and how to protect Fourth Estate Journalism”. Not only does the Editor of The Daily Blog, Martyn Bradbury, think this is a good idea, but he has also ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54435 days ago

Chris Trotter writes – Willie Jackson is said to be planning a “media summit” to discuss “the state of the media and how to protect Fourth Estate Journalism”. Not only does the Editor of The Daily Blog, Martyn Bradbury, think this is a good idea, but he has also ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54435 days ago - The Waitangi Tribunal Summons; or the more things stay the same

Graeme Edgeler writes – This morning [April 21], the Wellington High Court is hearing a judicial review brought by Hon. Karen Chhour, the Minister for Children, against a decision of the Waitangi Tribunal. This is unusual, judicial reviews are much more likely to brought against ministers, rather than ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54435 days ago

Graeme Edgeler writes – This morning [April 21], the Wellington High Court is hearing a judicial review brought by Hon. Karen Chhour, the Minister for Children, against a decision of the Waitangi Tribunal. This is unusual, judicial reviews are much more likely to brought against ministers, rather than ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54435 days ago - Both Parliamentary watchdogs hammer Fast-track bill

Both of Parliament’s watchdogs have now ripped into the Government’s Fast-track Approvals Bill. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMy pick of the six newsey things to know from Aotearoa’s political economy and beyond on the morning of Tuesday, April 23 are:The Lead: The Auditor General, John Ryan, has joined the ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

Both of Parliament’s watchdogs have now ripped into the Government’s Fast-track Approvals Bill. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMy pick of the six newsey things to know from Aotearoa’s political economy and beyond on the morning of Tuesday, April 23 are:The Lead: The Auditor General, John Ryan, has joined the ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - India makes a big bet on electric buses

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Sarah Spengeman People wait to board an electric bus in Pune, India. (Image credit: courtesy of ITDP) Public transportation riders in Pune, India, love the city’s new electric buses so much they will actually skip an older diesel bus that ...5 days ago

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Sarah Spengeman People wait to board an electric bus in Pune, India. (Image credit: courtesy of ITDP) Public transportation riders in Pune, India, love the city’s new electric buses so much they will actually skip an older diesel bus that ...5 days ago - Bernard’s pick ‘n’ mix of the news links at 6:36am on Tuesday, April 23

TL;DR: These six news links stood out in the last 24 hours to 6:36am on Tuesday, April 22:Scoop & Deep Dive: How Sir Peter Jackson got to have his billion-dollar exit cake and eat Hollywood too NZ Herald-$$$ Matt NippertFast Track Approval Bill: Watchdogs seek substantial curbs on ministers' powers ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

TL;DR: These six news links stood out in the last 24 hours to 6:36am on Tuesday, April 22:Scoop & Deep Dive: How Sir Peter Jackson got to have his billion-dollar exit cake and eat Hollywood too NZ Herald-$$$ Matt NippertFast Track Approval Bill: Watchdogs seek substantial curbs on ministers' powers ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - What is really holding up infrastructure

The infrastructure industry yesterday issued a “hurry up” message to the Government, telling it to get cracking on developing a pipeline of infrastructure projects.The hiatus around the change of Government has seen some major projects cancelled and others delayed, and there is uncertainty about what will happen with the new ...PolitikBy Richard Harman5 days ago

The infrastructure industry yesterday issued a “hurry up” message to the Government, telling it to get cracking on developing a pipeline of infrastructure projects.The hiatus around the change of Government has seen some major projects cancelled and others delayed, and there is uncertainty about what will happen with the new ...PolitikBy Richard Harman5 days ago - “Pure Unadulterated Charge”

Hi,Over the weekend I revisited a podcast I really adore, Dead Eyes. It’s about a guy who got fired from Band of Brothers over two decades ago because Tom Hanks said he had “dead eyes”.If you don’t recall — 2001’s Band of Brothers was part of the emerging trend of ...David FarrierBy David Farrier5 days ago

Hi,Over the weekend I revisited a podcast I really adore, Dead Eyes. It’s about a guy who got fired from Band of Brothers over two decades ago because Tom Hanks said he had “dead eyes”.If you don’t recall — 2001’s Band of Brothers was part of the emerging trend of ...David FarrierBy David Farrier5 days ago - Bernard's six-stack of substacks for Monday, April 22

Tonight’s six-stack includes: writes via his substack that’s he’s sceptical about the IPSOS poll last week suggesting a slide into authoritarianism here, writing: Kiwis seem to want their cake and eat it too Tal Aster writes for about How Israel turned homeowners into YIMBYs. writes via his ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago

Tonight’s six-stack includes: writes via his substack that’s he’s sceptical about the IPSOS poll last week suggesting a slide into authoritarianism here, writing: Kiwis seem to want their cake and eat it too Tal Aster writes for about How Israel turned homeowners into YIMBYs. writes via his ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey5 days ago - The media were given a little list and hastened to pick out Fast Track prospects – but the Treaty ...

Buzz from the Beehive The 180 or so recipients of letters from the Government telling them how to submit infrastructure projects for “fast track” consideration includes some whose project applications previously have been rejected by the courts. News media were quick to feature these in their reports after RMA Reform Minister Chris ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin6 days ago

Buzz from the Beehive The 180 or so recipients of letters from the Government telling them how to submit infrastructure projects for “fast track” consideration includes some whose project applications previously have been rejected by the courts. News media were quick to feature these in their reports after RMA Reform Minister Chris ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin6 days ago - Just trying to stay upright

It would not be a desirable way to start your holiday by breaking your back, your head, or your wrist, but on our first hour in Singapore I gave it a try.We were chatting, last week, before we started a meeting of Hazel’s Enviro Trust, about the things that can ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack6 days ago

It would not be a desirable way to start your holiday by breaking your back, your head, or your wrist, but on our first hour in Singapore I gave it a try.We were chatting, last week, before we started a meeting of Hazel’s Enviro Trust, about the things that can ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack6 days ago - “Unprecedented”

Today, former Port of Auckland CEO Tony Gibson went on trial on health and safety charges for the death of one of his workers. The Herald calls the trial "unprecedented". Firstly, it's only "unprecedented" because WorkSafe struck a corrupt and unlawful deal to drop charges against Peter Whittall over Pike ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago

Today, former Port of Auckland CEO Tony Gibson went on trial on health and safety charges for the death of one of his workers. The Herald calls the trial "unprecedented". Firstly, it's only "unprecedented" because WorkSafe struck a corrupt and unlawful deal to drop charges against Peter Whittall over Pike ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago - Bryce Edwards: Time for “Fast-Track Watch”

Calling all journalists, academics, planners, lawyers, political activists, environmentalists, and other members of the public who believe that the relationships between vested interests and politicians need to be scrutinised. We need to work together to make sure that the new Fast-Track Approvals Bill – currently being pushed through by the ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards6 days ago

Calling all journalists, academics, planners, lawyers, political activists, environmentalists, and other members of the public who believe that the relationships between vested interests and politicians need to be scrutinised. We need to work together to make sure that the new Fast-Track Approvals Bill – currently being pushed through by the ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards6 days ago - Gordon Campbell on fast track powers, media woes and the Tiktok ban

Feel worried. Shane Jones and a couple of his Cabinet colleagues are about to be granted the power to override any and all objections to projects like dams, mines, roads etc even if: said projects will harm biodiversity, increase global warming and cause other environmental harms, and even if ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon6 days ago

Feel worried. Shane Jones and a couple of his Cabinet colleagues are about to be granted the power to override any and all objections to projects like dams, mines, roads etc even if: said projects will harm biodiversity, increase global warming and cause other environmental harms, and even if ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon6 days ago - The Government’s new fast-track invitation to corruption

Bryce Edwards writes- The ability of the private sector to quickly establish major new projects making use of the urban and natural environment is to be supercharged by the new National-led Government. Yesterday it introduced to Parliament one of its most significant reforms, the Fast Track Approvals Bill. ...Point of OrderBy gadams10006 days ago

Bryce Edwards writes- The ability of the private sector to quickly establish major new projects making use of the urban and natural environment is to be supercharged by the new National-led Government. Yesterday it introduced to Parliament one of its most significant reforms, the Fast Track Approvals Bill. ...Point of OrderBy gadams10006 days ago - Maori push for parallel government structures

Michael Bassett writes – If you think there is a move afoot by the radical Maori fringe of New Zealand society to create a parallel system of government to the one that we elect at our triennial elections, you aren’t wrong. Over the last few days we have ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54436 days ago

Michael Bassett writes – If you think there is a move afoot by the radical Maori fringe of New Zealand society to create a parallel system of government to the one that we elect at our triennial elections, you aren’t wrong. Over the last few days we have ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54436 days ago - An announcement about an announcement

Without a corresponding drop in interest rates, it’s doubtful any changes to the CCCFA will unleash a massive rush of home buyers. Photo: Lynn GrievesonTL;DR: The six things that stood out to me in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, poverty and climate on Monday, April 22 included:The Government making a ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago

Without a corresponding drop in interest rates, it’s doubtful any changes to the CCCFA will unleash a massive rush of home buyers. Photo: Lynn GrievesonTL;DR: The six things that stood out to me in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, poverty and climate on Monday, April 22 included:The Government making a ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago - All the Green Tech in China.

Sunday was a lazy day. I started watching Jack Tame on Q&A, the interviews are usually good for something to write about. Saying the things that the politicians won’t, but are quite possibly thinking. Things that are true and need to be extracted from between the lines.As you might know ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel6 days ago

Sunday was a lazy day. I started watching Jack Tame on Q&A, the interviews are usually good for something to write about. Saying the things that the politicians won’t, but are quite possibly thinking. Things that are true and need to be extracted from between the lines.As you might know ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel6 days ago - Western Express Success

In our Weekly Roundup last week we covered news from Auckland Transport that the WX1 Western Express is going to get an upgrade next year with double decker electric buses. As part of the announcement, AT also said “Since we introduced the WX1 Western Express last November we have seen ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L6 days ago

In our Weekly Roundup last week we covered news from Auckland Transport that the WX1 Western Express is going to get an upgrade next year with double decker electric buses. As part of the announcement, AT also said “Since we introduced the WX1 Western Express last November we have seen ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L6 days ago - Bernard’s pick ‘n’ mix of the news links at 7:16am on Monday, April 22

TL;DR: These six news links stood out in the last 24 hours to 7:16am on Monday, April 22:Labour says Kiwis at greater risk from loan sharks as Govt plans to remove borrowing regulations NZ Herald Jenee TibshraenyHow did the cost of moving two schools blow out to more than $400m?A ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago

TL;DR: These six news links stood out in the last 24 hours to 7:16am on Monday, April 22:Labour says Kiwis at greater risk from loan sharks as Govt plans to remove borrowing regulations NZ Herald Jenee TibshraenyHow did the cost of moving two schools blow out to more than $400m?A ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago - The Kaka’s diary for the week to April 29 and beyond

TL;DR: The six key events to watch in Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy in the week to April 29 include:PM Christopher Luxon is scheduled to hold a post-Cabinet news conference at 4 pm today. Stats NZ releases its statutory report on Census 2023 tomorrow.Finance Minister Nicola Willis delivers a pre-Budget speech at ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago

TL;DR: The six key events to watch in Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy in the week to April 29 include:PM Christopher Luxon is scheduled to hold a post-Cabinet news conference at 4 pm today. Stats NZ releases its statutory report on Census 2023 tomorrow.Finance Minister Nicola Willis delivers a pre-Budget speech at ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago - 2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #16

A listing of 29 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, April 14, 2024 thru Sat, April 20, 2024. Story of the week Our story of the week hinges on these words from the abstract of a fresh academic ...6 days ago

A listing of 29 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, April 14, 2024 thru Sat, April 20, 2024. Story of the week Our story of the week hinges on these words from the abstract of a fresh academic ...6 days ago - Bryce Edwards: The Government’s new fast-track invitation to corruption

The ability of the private sector to quickly establish major new projects making use of the urban and natural environment is to be supercharged by the new National-led Government. Yesterday it introduced to Parliament one of its most significant reforms, the Fast Track Approvals Bill. The Government says this will ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards7 days ago

The ability of the private sector to quickly establish major new projects making use of the urban and natural environment is to be supercharged by the new National-led Government. Yesterday it introduced to Parliament one of its most significant reforms, the Fast Track Approvals Bill. The Government says this will ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards7 days ago - Thank you

This is a column to say thank you. So many of have been in touch since Mum died to say so many kind and thoughtful things. You’re wonderful, all of you. You’ve asked how we’re doing, how Dad’s doing. A little more realisation each day, of the irretrievable finality of ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 week ago

This is a column to say thank you. So many of have been in touch since Mum died to say so many kind and thoughtful things. You’re wonderful, all of you. You’ve asked how we’re doing, how Dad’s doing. A little more realisation each day, of the irretrievable finality of ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 week ago - Determining the Engine Type in Your Car

Identifying the engine type in your car is crucial for various reasons, including maintenance, repairs, and performance upgrades. Knowing the specific engine model allows you to access detailed technical information, locate compatible parts, and make informed decisions about modifications. This comprehensive guide will provide you with a step-by-step approach to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Identifying the engine type in your car is crucial for various reasons, including maintenance, repairs, and performance upgrades. Knowing the specific engine model allows you to access detailed technical information, locate compatible parts, and make informed decisions about modifications. This comprehensive guide will provide you with a step-by-step approach to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - How to Become a Race Car Driver: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction: The allure of racing is undeniable. The thrill of speed, the roar of engines, and the exhilaration of competition all contribute to the allure of this adrenaline-driven sport. For those who yearn to experience the pinnacle of racing, becoming a race car driver is the ultimate dream. However, the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Introduction: The allure of racing is undeniable. The thrill of speed, the roar of engines, and the exhilaration of competition all contribute to the allure of this adrenaline-driven sport. For those who yearn to experience the pinnacle of racing, becoming a race car driver is the ultimate dream. However, the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - How Many Cars Are There in the World in 2023? An Exploration of Global Automotive Statistics

Introduction Automobiles have become ubiquitous in modern society, serving as a primary mode of transportation and a symbol of economic growth and personal mobility. With countless vehicles traversing roads and highways worldwide, it begs the question: how many cars are there in the world? Determining the precise number is a ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Introduction Automobiles have become ubiquitous in modern society, serving as a primary mode of transportation and a symbol of economic growth and personal mobility. With countless vehicles traversing roads and highways worldwide, it begs the question: how many cars are there in the world? Determining the precise number is a ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - How Long Does It Take for Car Inspection?

Maintaining a safe and reliable vehicle requires regular inspections. Whether it’s a routine maintenance checkup or a safety inspection, knowing how long the process will take can help you plan your day accordingly. This article delves into the factors that influence the duration of a car inspection and provides an ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Maintaining a safe and reliable vehicle requires regular inspections. Whether it’s a routine maintenance checkup or a safety inspection, knowing how long the process will take can help you plan your day accordingly. This article delves into the factors that influence the duration of a car inspection and provides an ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - Who Makes Mazda Cars?

Mazda Motor Corporation, commonly known as Mazda, is a Japanese multinational automaker headquartered in Fuchu, Aki District, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. The company was founded in 1920 as the Toyo Cork Kogyo Co., Ltd., and began producing vehicles in 1931. Mazda is primarily known for its production of passenger cars, but ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Mazda Motor Corporation, commonly known as Mazda, is a Japanese multinational automaker headquartered in Fuchu, Aki District, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. The company was founded in 1920 as the Toyo Cork Kogyo Co., Ltd., and began producing vehicles in 1931. Mazda is primarily known for its production of passenger cars, but ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - How Often to Replace Your Car Battery A Comprehensive Guide

Your car battery is an essential component that provides power to start your engine, operate your electrical systems, and store energy. Over time, batteries can weaken and lose their ability to hold a charge, which can lead to starting problems, power failures, and other issues. Replacing your battery before it ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Your car battery is an essential component that provides power to start your engine, operate your electrical systems, and store energy. Over time, batteries can weaken and lose their ability to hold a charge, which can lead to starting problems, power failures, and other issues. Replacing your battery before it ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - Can You Register a Car Without a License?

In most states, you cannot register a car without a valid driver’s license. However, there are a few exceptions to this rule. Exceptions to the Rule If you are under 18 years old: In some states, you can register a car in your name even if you do not ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

In most states, you cannot register a car without a valid driver’s license. However, there are a few exceptions to this rule. Exceptions to the Rule If you are under 18 years old: In some states, you can register a car in your name even if you do not ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - Mazda: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Reliability, Value, and Performance

Mazda, a Japanese automotive manufacturer with a rich history of innovation and engineering excellence, has emerged as a formidable player in the global car market. Known for its reputation of producing high-quality, fuel-efficient, and driver-oriented vehicles, Mazda has consistently garnered praise from industry experts and consumers alike. In this article, ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Mazda, a Japanese automotive manufacturer with a rich history of innovation and engineering excellence, has emerged as a formidable player in the global car market. Known for its reputation of producing high-quality, fuel-efficient, and driver-oriented vehicles, Mazda has consistently garnered praise from industry experts and consumers alike. In this article, ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - What Are Struts on a Car?

Struts are an essential part of a car’s suspension system. They are responsible for supporting the weight of the car and damping the oscillations of the springs. Struts are typically made of steel or aluminum and are filled with hydraulic fluid. How Do Struts Work? Struts work by transferring the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Struts are an essential part of a car’s suspension system. They are responsible for supporting the weight of the car and damping the oscillations of the springs. Struts are typically made of steel or aluminum and are filled with hydraulic fluid. How Do Struts Work? Struts work by transferring the ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - What Does Car Registration Look Like: A Comprehensive Guide

Car registration is a mandatory process that all vehicle owners must complete annually. This process involves registering your car with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and paying an associated fee. The registration process ensures that your vehicle is properly licensed and insured, and helps law enforcement and other authorities ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Car registration is a mandatory process that all vehicle owners must complete annually. This process involves registering your car with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and paying an associated fee. The registration process ensures that your vehicle is properly licensed and insured, and helps law enforcement and other authorities ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - How to Share Computer Audio on Zoom

Zoom is a video conferencing service that allows you to share your screen, webcam, and audio with other participants. In addition to sharing your own audio, you can also share the audio from your computer with other participants. This can be useful for playing music, sharing presentations with audio, or ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Zoom is a video conferencing service that allows you to share your screen, webcam, and audio with other participants. In addition to sharing your own audio, you can also share the audio from your computer with other participants. This can be useful for playing music, sharing presentations with audio, or ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago - How Long Does It Take to Build a Computer?

Building your own computer can be a rewarding and cost-effective way to get a high-performance machine tailored to your specific needs. However, it also requires careful planning and execution, and one of the most important factors to consider is the time it will take. The exact time it takes to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Building your own computer can be a rewarding and cost-effective way to get a high-performance machine tailored to your specific needs. However, it also requires careful planning and execution, and one of the most important factors to consider is the time it will take. The exact time it takes to ...Gareth’s WorldBy admin1 week ago

Related Posts

- Gaza: Aotearoa Must Support Independent Investigation into Mass Graves

Te Pāti Māori are demanding the New Zealand Government support an international independent investigation into mass graves that have been uncovered at two hospitals on the Gaza strip, following weeks of assault by Israeli troops. Among the 392 bodies that have been recovered, are children and elderly civilians. Many of ...2 days ago

Te Pāti Māori are demanding the New Zealand Government support an international independent investigation into mass graves that have been uncovered at two hospitals on the Gaza strip, following weeks of assault by Israeli troops. Among the 392 bodies that have been recovered, are children and elderly civilians. Many of ...2 days ago - Release: Working together on consistent support for veterans this Anzac Day

Our two-tiered system for veterans’ support is out of step with our closest partners, and all parties in Parliament should work together to fix it, Labour veterans’ affairs spokesperson Greg O’Connor said. ...4 days ago

Our two-tiered system for veterans’ support is out of step with our closest partners, and all parties in Parliament should work together to fix it, Labour veterans’ affairs spokesperson Greg O’Connor said. ...4 days ago - Release: Penny drops – but what about Seymour and Peters?

Stripping two Ministers of their portfolios just six months into the job shows Christopher Luxon’s management style is lacking, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said. ...4 days ago

Stripping two Ministers of their portfolios just six months into the job shows Christopher Luxon’s management style is lacking, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said. ...4 days ago - Another ‘Stolen Generation’ enabled by court ruling on Waitangi Tribunal summons

Tonight’s court decision to overturn the summons of the Children’s Minister has enabled the Crown to continue making decisions about Māori without evidence, says Te Pāti Māori spokesperson for Children, Mariameno Kapa-Kingi. “The judicial system has this evening told the nation that this government can do whatever they want when ...4 days ago

Tonight’s court decision to overturn the summons of the Children’s Minister has enabled the Crown to continue making decisions about Māori without evidence, says Te Pāti Māori spokesperson for Children, Mariameno Kapa-Kingi. “The judicial system has this evening told the nation that this government can do whatever they want when ...4 days ago - Release: Budget blunder shows Nicola Willis could cut recovery funding

It appears Nicola Willis is about to pull the rug out from under the feet of local communities still dealing with the aftermath of last year’s severe weather, and local councils relying on funding to build back from these disasters. ...5 days ago

It appears Nicola Willis is about to pull the rug out from under the feet of local communities still dealing with the aftermath of last year’s severe weather, and local councils relying on funding to build back from these disasters. ...5 days ago - Further environmental mismanagement on the cards

The Government’s resource management reforms will add to the heavy and ever-growing burden this Government is loading on to our environment. ...5 days ago

The Government’s resource management reforms will add to the heavy and ever-growing burden this Government is loading on to our environment. ...5 days ago - Release: RMA changes will be a disaster for environment

The Government is making short-sighted changes to the Resource Management Act (RMA) that will take away environmental protection in favour of short-term profits, Labour’s environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said today. ...5 days ago

The Government is making short-sighted changes to the Resource Management Act (RMA) that will take away environmental protection in favour of short-term profits, Labour’s environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said today. ...5 days ago - Release: Labour supports urgent changes to emergency management system

Labour welcomes the release of the report into the North Island weather events and looks forward to working with the Government to ensure that New Zealand is as prepared as it can be for the next natural disaster. ...5 days ago

Labour welcomes the release of the report into the North Island weather events and looks forward to working with the Government to ensure that New Zealand is as prepared as it can be for the next natural disaster. ...5 days ago - Release: Labour calls for New Zealand to recognise Palestine

The Labour Party has called for the New Zealand Government to recognise Palestine, as a material step towards progressing the two-State solution needed to achieve a lasting peace in the region. ...6 days ago

The Labour Party has called for the New Zealand Government to recognise Palestine, as a material step towards progressing the two-State solution needed to achieve a lasting peace in the region. ...6 days ago - Release: Three strikes law political posturing of worst kind

The Government is bringing back a law that has little evidential backing just to look tough, Labour justice spokesperson Duncan Webb said. ...6 days ago

The Government is bringing back a law that has little evidential backing just to look tough, Labour justice spokesperson Duncan Webb said. ...6 days ago - Release: Government cuts unbelievably target child exploitation, violent extremism, ports and airpor...

Some of our country’s most important work, stopping the sexual exploitation of children and violent extremism could go along with staff on the frontline at ports and airports. ...6 days ago

Some of our country’s most important work, stopping the sexual exploitation of children and violent extremism could go along with staff on the frontline at ports and airports. ...6 days ago - Three strikes has failed before and will fail again

Resurrecting the archaic three-strikes legislation is an unwelcome return to a failed American-style approach to justice. ...6 days ago

Resurrecting the archaic three-strikes legislation is an unwelcome return to a failed American-style approach to justice. ...6 days ago - Release: Environmental protection vital, not ‘onerous’

The Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill will give projects such as new coal mines a ‘get out of jail free’ card to wreak havoc on the environment, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said today. ...6 days ago

The Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill will give projects such as new coal mines a ‘get out of jail free’ card to wreak havoc on the environment, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said today. ...6 days ago - Ferris – Three Strikes targets those ‘too brown to be white’

The government's decision to reintroduce Three Strikes is a destructive and ineffective piece of law-making that will only exacerbate an inherently biased and racist criminal justice system, said Te Pāti Māori Justice Spokesperson, Tākuta Ferris, today. During the time Three Strikes was in place in Aotearoa, Māori and Pasifika received ...6 days ago

The government's decision to reintroduce Three Strikes is a destructive and ineffective piece of law-making that will only exacerbate an inherently biased and racist criminal justice system, said Te Pāti Māori Justice Spokesperson, Tākuta Ferris, today. During the time Three Strikes was in place in Aotearoa, Māori and Pasifika received ...6 days ago - Release: Govt cuts doctors and nurses in hiring freeze

Cuts to frontline hospital staff are not only a broken election promise, it shows the reckless tax cuts have well and truly hit the frontline of the health system, says Labour Health spokesperson Ayesha Verrall. ...1 week ago

Cuts to frontline hospital staff are not only a broken election promise, it shows the reckless tax cuts have well and truly hit the frontline of the health system, says Labour Health spokesperson Ayesha Verrall. ...1 week ago - Fast-track submissions period must be extended

The Green Party has joined the call for public submissions on the fast-track legislation to be extended after the Ombudsman forced the Government to release the list of organisations invited to apply just hours before submissions close. ...1 week ago

The Green Party has joined the call for public submissions on the fast-track legislation to be extended after the Ombudsman forced the Government to release the list of organisations invited to apply just hours before submissions close. ...1 week ago - Release: Progress on climate will be undone by Govt

New Zealand’s good work at reducing climate emissions for three years in a row will be undone by the National government’s lack of ambition and scrapping programmes that were making a difference, Labour Party climate spokesperson Megan Woods said today. ...1 week ago

New Zealand’s good work at reducing climate emissions for three years in a row will be undone by the National government’s lack of ambition and scrapping programmes that were making a difference, Labour Party climate spokesperson Megan Woods said today. ...1 week ago - Release: Dark day for Kiwi kids as a third of Govt cuts affect them

News that 1000 jobs at the Ministry of Education and Oranga Tamariki could go is devastating for future generations of New Zealanders. ...2 weeks ago

News that 1000 jobs at the Ministry of Education and Oranga Tamariki could go is devastating for future generations of New Zealanders. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Alarm as Government signals further blow to school lunches

More essential jobs could be on the chopping block, this time Ministry of Education staff on the school lunches team are set to find out whether they're in line to lose their jobs. ...2 weeks ago

More essential jobs could be on the chopping block, this time Ministry of Education staff on the school lunches team are set to find out whether they're in line to lose their jobs. ...2 weeks ago - Oranga Tamariki cuts commit tamariki to state abuse

Te Pāti Māori is disgusted at the confirmation that hundreds are set to lose their jobs at Oranga Tamariki, and the disestablishment of the Treaty Response Unit. “This act of absolute carelessness and out of touch decision making is committing tamariki to state abuse.” Said Te Pāti Māori Oranga Tamariki ...2 weeks ago

Te Pāti Māori is disgusted at the confirmation that hundreds are set to lose their jobs at Oranga Tamariki, and the disestablishment of the Treaty Response Unit. “This act of absolute carelessness and out of touch decision making is committing tamariki to state abuse.” Said Te Pāti Māori Oranga Tamariki ...2 weeks ago - Release: Quick, submit – stop Govt’s dodgy approvals bill

The Government is trying to bring in a law that will allow Ministers to cut corners and kill off native species, Labour environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said. ...2 weeks ago

The Government is trying to bring in a law that will allow Ministers to cut corners and kill off native species, Labour environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said. ...2 weeks ago - Government throws coal on the climate crisis fire