Wanted: Dead or Alive? The Treaty of Waitangi

Wanted: Dead or Alive? The Treaty of Waitangi

Written By:

Incognito - Date published:

1:55 pm, December 17th, 2023 - 28 comments

Categories: Deep stuff -

Tags: living document, originalism, te tiriti o waitangi, Treaty of waitangi

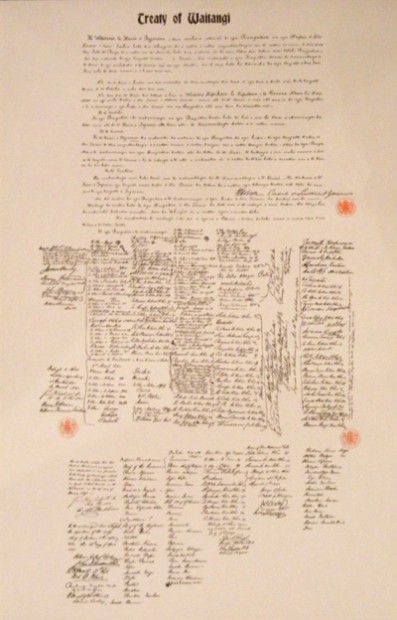

Some would like to the Treaty buried in a museum archive or even better, burnt forever on a bonfire (and together with Regulations). Some may not object to having their version in full view and the other in a dark dusty display in a far corner of the History section. Some treat the Treaty as a guide or manual for NZ society. There are many different views of the style and the substance of the Te Tiriti – the Treaty. Likewise, the path of public discourse is broadly divided into tracks of deliberation versus persuasion, with the former being pluralistic, inclusive, constructive, compromising, rational, and respectful and the latter being binary, exclusive, antagonistic, polarising, emotive, and contemptuous. Suffice to say, the paths will lead to different destinations.

Only two days ago, Anne Salmond wrote another excellent piece on the Treaty in which she juxtaposes different ways of thinking.

Different ways of thinking can put people at loggerheads, so they talk past each other – reasonable people who reason differently. This can create impasses that are almost intractable. Current discussions over Te Tiriti o Waitangi may be a case in point.

However, Anne Salmond’s piece doesn’t pre-empt this Post, for which I already had an advanced draft, and they sit nicely side-by-side.

While the debate regarding the Treaty continues and is heating up, I’d like to focus on two main perspectives that are often ignored in the public discourse and that appear to be confined to academic circles: the ‘Living Document’ and ‘Originalism’.

The ‘Living Document’ perspective 1 suggests that the Treaty’s interpretation should evolve over time, reflecting changing societal values and circumstances. This viewpoint allows the Treaty to remain relevant and adaptable, addressing issues unforeseen at the time of its signing in 1840. It acknowledges the dynamic nature of the relationship between Māori and the Crown and by implication, between all peoples in and of Aotearoa – New Zealand. When this view comes into focus, it is embraced wholeheartedly or rejected in a business-like manner.

A comparison can be made of the Treaty to the evolution of law and democracy.

Law is often considered a ‘living’ entity, as it is interpreted and reinterpreted by courts, and updated through amendments or new legislation to reflect societal changes. This process allows the law to remain relevant and adaptable, much like the ‘living document’ perspective of the Treaty.

Similarly, democracy has evolved over centuries to adapt to changing societal values and circumstances. The adoption of the mixed-member proportional representation (MMP) system in New Zealand in the 1990s is a prime example of this evolution. It represented a significant change to the electoral system to reflect better the diversity of views within the population.

These examples lend support to the perspective of the Treaty as a ‘living document’. They highlight the importance of adaptability and evolution in maintaining the relevance of such foundational documents and systems in a changing dynamic society. This perspective allows for the ongoing development of the relationship between Māori and the Crown, and the continual reassessment and resolution of Treaty claims.

Conversely, the ‘Originalism’ perspective 2 argues for an interpretation based on the original intent and understanding at the time the Treaty was signed. This view emphasises the historical context and the specific words used in the Treaty. However, applying originalism to the Treaty of Waitangi has its limitations due to the differences between the Māori and English texts and the manner in which the Treaty’s provisions were devised, drafted, and subsequently acceded.

The debate becomes more complex when considering the socio-economic disparities faced by Māori people. Some stakeholders argue for a multi-ethnic society without favouritism based on race or ethnicity. However, this perspective can overlook the historical and ongoing inequities faced by the Māori people. The Treaty was intended to protect Māori rights and interests, and many argue that this includes addressing socio-economic disparities and historical injustices.

The political landscape and the diametrically and ideologically (!) opposed new Government, relative to the previous one, further complicate the debate. The lack of Māori representation in the government can be a concern for those seeking to ensure that Māori rights and interests are adequately addressed. The push for a referendum on the Treaty by a coalition party reflects one perspective in the debate. However, even though a referendum is a democratic process that allows all eligible voters to have a say and that could potentially provide an opportunity for a broader public discussion about the Treaty and its implications, the actual nature of the debate is crucial for the outcome.

Both the nature of the Treaty (i.e. Living Document vs. Originalism Perspective) and the question about the interpretation of the Treaty document (i.e. English vs. Māori version) are crucial aspects that contribute to the overall understanding and application of the Treaty.

The nature of the Treaty, whether it’s viewed as a living document or through the lens of originalism, can influence how its principles are applied in contemporary society. This perspective can shape policies, legal decisions, and societal attitudes towards the Treaty.

The interpretation of the Treaty, particularly the differences between the English and Māori versions, is also a significant factor. It directly impacts on the understanding of the Treaty’s intentions and the rights and obligations of the parties involved.

In an ideal scenario, these aspects should not be mutually exclusive but should inform each other to ensure a comprehensive and respectful approach to the Treaty of Waitangi – the people of Aotearoa – New Zealand deserve no less.

What is the path forward? It’s clear that (public) opinion of the Treaty involves a range of perspectives and interests. It’s a complex issue that requires ongoing dialogue and mutual respect. In my opinion, the Treaty, much like the evolution of law and democracy, is a living entity that should adapt to the changing societal values and circumstances. It’s crucial that all stakeholders, including Māori, are genuinely engaged in these discussions. The goal should be justice and reconciliation, guided by the principles of the Treaty.

Looking at the future, let’s imagine a New Zealand where socio-economic disparities have been all but eliminated. In this future, Māori health outcomes are no longer disproportionately poor compared to the rest of the population. Māori life expectancy matches, if not exceeds, the national average. Māori children grow up with the same opportunities for education and employment as their peers, unhampered by the socio-economic constraints of their ancestors. In other words, Māori are uplifted and they’ll have the same outcomes.

In this vision, the principles of the Treaty are fully realised. Te Reo flourishes in schools, in media, and in everyday conversation, reflecting a society that values and preserves its indigenous culture. Māori people have an influential voice in the government, ensuring their rights and interests are always properly represented.

Land and other natural resources returned through Treaty settlements is managed sustainably, benefiting both the Māori iwi (tribes) and the wider community, and future generations. The relationship between Māori and the Crown is characterised by mutual respect and collaborative relationship, as originally intended by the Treaty.

Working backwards from this vision, we can identify key steps towards achieving this future:

- Address Health Disparities: Implement health policies and programs that specifically target areas where Māori health outcomes are currently lagging.

- Promote Māori Language and Culture: Encourage the teaching and use of Te Reo in schools and public life. Recognise and celebrate Māori culture and traditions.

- Ensure Māori Representation: Advocate for greater Māori representation in government and other decision-making bodies.

- Honour Treaty Settlements: Ensure that land returned through Treaty settlements is managed in a way that benefits Māori communities and respects their cultural connection to the land.

- Foster Mutual Respect and Relationship: Promote understanding and respect between Māori and non-Māori communities. Encourage relationships that honour the principles of the Treaty.

I believe this is a future we can all look forward to, without fear and prejudice, and it provides a possible roadmap for how New Zealand can move forward. I think it’s a future worth striving for.

Related Posts

28 comments on “Wanted: Dead or Alive? The Treaty of Waitangi ”

- Comments are now closed

- Comments are now closed

Recent Comments

- Kay to mickysavage on

- Cinder to mickysavage on

- SPC on

- mickysavage to Traveller on

- Cricklewood on

- SPC on

- Traveller on

- Nic the NZer to Traveller on

- Ad on

- D on

- Kat on

- mac1 to Phillip ure on

- mac1 on

- Peter on

- Anne on

- Subliminal to Bearded Git on

- Traveller to Bearded Git on

- Anne to Belladonna on

- Nic the NZer to Traveller on

- Phillip ure on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Reality on

- Anne to Mike the Lefty on

- Nic the NZer to Traveller on

- Phillip ure to Phillip ure on

- Phillip ure to Belladonna on

- roblogic on

- Nic the NZer to Traveller on

- Nic the NZer to Traveller on

- Belladonna to Ad on

- Belladonna to James Simpson on

- weka to James Simpson on

- Belladonna to Jilly Bee on

- Obtrectator on

- Bearded Git to weka on

- Visubversa to weka on

- Subliminal to Sanctuary on

- James Simpson to Darien Fenton on

- weka to Bearded Git on

- Belladonna to Reality on

- Tiger Mountain to Drowsy M. Kram on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Jimmy on

- David to Bearded Git on

- Ad on

- Nic the NZer to Traveller on

- Ad on

- Jimmy on

- Jimmy to Drowsy M. Kram on

- bwaghorn to Darien Fenton on

- Bearded Git to weka on

- newsense on

- Drowsy M. Kram to Jimmy on

- newsense to Bearded Git on

- weka to Darien Fenton on

- Darien Fenton to weka on

- Reality on

- Jimmy to Mike the Lefty on

- weka on

- weka to Mike the Lefty on

- weka to Mike the Lefty on

- Mike the Lefty to Jimmy on

- Jimmy to Mike the Lefty on

- weka on

- James Simpson to Mike the Lefty on

- weka to Darien Fenton on

- Phillip ure to dv on

- Mike the Lefty to Jimmy on

- Phillip ure to Subliminal on

- Belladonna to mpledger on

- mikesh on

- Nic the NZer to alwyn on

- Belladonna to Graeme on

- Phillip ure to Traveller on

- dv on

- Cricklewood to Jimmy on

- alwyn to Subliminal on

Recent Posts

-

by mickysavage

-

by nickkelly

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by mickysavage

-

by advantage

-

by advantage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by Guest post

-

by advantage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by advantage

-

by weka

-

by nickkelly

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by mickysavage

- Pamphlets at Ten Paces.

These puppet strings don't pull themselvesYou're thinking thoughts from someone elseHow much time do you think you have?Are you prepared for what comes next?The debating chamber can be a trying place for an opposition MP. What with the person in charge, the speaker, typically being an MP from the governing ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel54 mins ago

These puppet strings don't pull themselvesYou're thinking thoughts from someone elseHow much time do you think you have?Are you prepared for what comes next?The debating chamber can be a trying place for an opposition MP. What with the person in charge, the speaker, typically being an MP from the governing ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel54 mins ago - A land without pier

The land around Lyme Regis, where Meryl Streep once stood, in a hood, on the Cobb, is falling into the sea.MerylThe land around Lyme Regis, around the Cobb that made it rich, has always been falling slowly but surely into the sea. Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 hour ago

The land around Lyme Regis, where Meryl Streep once stood, in a hood, on the Cobb, is falling into the sea.MerylThe land around Lyme Regis, around the Cobb that made it rich, has always been falling slowly but surely into the sea. Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 hour ago - Skeptical Science New Research for Week #18 2024

Open access notables Generative AI tools can enhance climate literacy but must be checked for biases and inaccuracies, Atkins et al., Communications Earth & Environment: In the face of climate change, climate literacy is becoming increasingly important. With wide access to generative AI tools, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, we explore the potential ...13 hours ago

Open access notables Generative AI tools can enhance climate literacy but must be checked for biases and inaccuracies, Atkins et al., Communications Earth & Environment: In the face of climate change, climate literacy is becoming increasingly important. With wide access to generative AI tools, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, we explore the potential ...13 hours ago - Ruckus over AUKUS – Labour demands Peters step down as Foreign Minister, but he still had the job ...

Buzz from the Beehive Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters was bound to win headlines when he set out his thinking about AUKUS in his speech to the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs. The headlines became bigger when – during an interview on RNZ’s Morning Report today – he criticised ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin16 hours ago

Buzz from the Beehive Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters was bound to win headlines when he set out his thinking about AUKUS in his speech to the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs. The headlines became bigger when – during an interview on RNZ’s Morning Report today – he criticised ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin16 hours ago - Secrecy undermines participation

The Post reports on how the government is refusing to release its advice on its corrupt Muldoonist fast-track law, instead using the "soon to be publicly available" refusal ground to hide it until after select committee submissions on the bill have closed. Fast-track Minister Chris Bishop's excuse? “It's not ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant16 hours ago

The Post reports on how the government is refusing to release its advice on its corrupt Muldoonist fast-track law, instead using the "soon to be publicly available" refusal ground to hide it until after select committee submissions on the bill have closed. Fast-track Minister Chris Bishop's excuse? “It's not ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant16 hours ago - Agribusiness following oil and gas playbookAs pressure on it grows, the livestock industry’s approach to the transition to Net Zero is increasingly being compared to that of fossil fuel interests. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / Getty ImagesTL;DR: Here’s the top five news items of note in climate news for Aotearoa-NZ this week, and a discussion above ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey17 hours ago

- Here’s hoping they aren’t counting on a 100 per cent acceptance…

The New Zealand Herald reports – Stats NZ has offered a voluntary redundancy scheme to all of its workers as a way to give staff some control over their “future” amidst widespread job losses in the public sector. In an update to staff this morning, seen by the Herald, Statistics New Zealand ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin19 hours ago

The New Zealand Herald reports – Stats NZ has offered a voluntary redundancy scheme to all of its workers as a way to give staff some control over their “future” amidst widespread job losses in the public sector. In an update to staff this morning, seen by the Herald, Statistics New Zealand ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin19 hours ago - Gordon Campbell on unemployment, Winston Peters’ low boiling point and music criticism

On Werewolf/Scoop, I usually do two long form political columns a week. From now on, there will be an extra column each week about music and movies. But first, some late-breaking political events: The rise in unemployment numbers for the March quarter was bigger than expected – and especially sharp ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon19 hours ago

On Werewolf/Scoop, I usually do two long form political columns a week. From now on, there will be an extra column each week about music and movies. But first, some late-breaking political events: The rise in unemployment numbers for the March quarter was bigger than expected – and especially sharp ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon19 hours ago - TVNZ and poll resultsPoint of OrderBy poonzteam544320 hours ago

- Mana or Money

Muriel Newman writes – When Meridian Energy was seeking resource consents for a West Coast hydro dam proposal in 2010, local Maori “strenuously” objected, claiming their mana was inextricably linked to ‘their’ river and could be damaged. After receiving a financial payment from the company, however, the Ngai Tahu ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544320 hours ago

Muriel Newman writes – When Meridian Energy was seeking resource consents for a West Coast hydro dam proposal in 2010, local Maori “strenuously” objected, claiming their mana was inextricably linked to ‘their’ river and could be damaged. After receiving a financial payment from the company, however, the Ngai Tahu ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544320 hours ago - Bernard’s pick 'n' mix for Thursday, May 2

TL;DR: Here’s my top 10 ‘pick ‘n’ mix of links to news, analysis and opinion articles as of 11:10 am on Thursday, May 2:Scoop: Government sits on official advice on fast-track consent. The Ombudsman is investigating after official briefings on the contentious regime were held back despite requests from Forest ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey21 hours ago

TL;DR: Here’s my top 10 ‘pick ‘n’ mix of links to news, analysis and opinion articles as of 11:10 am on Thursday, May 2:Scoop: Government sits on official advice on fast-track consent. The Ombudsman is investigating after official briefings on the contentious regime were held back despite requests from Forest ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey21 hours ago - The Art of taking no Responsibility

Alwyn Poole writes – “An SEP,’ he said, ‘is something that we can’t see, or don’t see, or our brain doesn’t let us see, because we think that it’s somebody else’s problem. That’s what SEP means. Somebody Else’s Problem. The brain just edits it out, it’s like a ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544321 hours ago

Alwyn Poole writes – “An SEP,’ he said, ‘is something that we can’t see, or don’t see, or our brain doesn’t let us see, because we think that it’s somebody else’s problem. That’s what SEP means. Somebody Else’s Problem. The brain just edits it out, it’s like a ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544321 hours ago - The shabby “Parliamentary urgency” ploy – shaky foundations and why our democracy needs trust

Our trust in our political institutions is fast eroding, according to a Maxim Institute discussion paper, Shaky Foundations: Why our democracy needs trust. The paper – released today – raises concerns about declining trust in New Zealand’s political institutions and democratic processes, and the role that the overuse of Parliamentary urgency ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544321 hours ago

Our trust in our political institutions is fast eroding, according to a Maxim Institute discussion paper, Shaky Foundations: Why our democracy needs trust. The paper – released today – raises concerns about declining trust in New Zealand’s political institutions and democratic processes, and the role that the overuse of Parliamentary urgency ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam544321 hours ago - Jones has made plain he isn’t fond of frogs (not the dim-witted ones, at least) – and now we lea...

This article was prepared for publication yesterday. More ministerial announcements have been posted on the government’s official website since it was written. We will report on these later today …. Buzz from the Beehive There we were, thinking the environment is in trouble, when along came Jones. Shane Jones. ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin22 hours ago

This article was prepared for publication yesterday. More ministerial announcements have been posted on the government’s official website since it was written. We will report on these later today …. Buzz from the Beehive There we were, thinking the environment is in trouble, when along came Jones. Shane Jones. ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin22 hours ago - Infrastructure & home building slumping on Govt funding freezeThe KakaBy Bernard Hickey23 hours ago

- Brainwashed People Think Everyone Else is Brainwashed

Hi,I am just going to state something very obvious: American police are fucking crazy.That was a photo gracing the New York Times this morning, showing New York City police “entering Columbia University last night after receiving a request from the school.”Apparently in America, protesting the deaths of tens of thousands ...David FarrierBy David Farrier1 day ago

Hi,I am just going to state something very obvious: American police are fucking crazy.That was a photo gracing the New York Times this morning, showing New York City police “entering Columbia University last night after receiving a request from the school.”Apparently in America, protesting the deaths of tens of thousands ...David FarrierBy David Farrier1 day ago - Peters’ real foreign policy threat is Helen Clark

Winston Peters’ much anticipated foreign policy speech last night was a work of two halves. Much of it was a standard “boilerplate” Foreign Ministry overview of the state of the world. There was some hardening up of rhetoric with talk of “benign” becoming “malign” and old truths giving way to ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 day ago

Winston Peters’ much anticipated foreign policy speech last night was a work of two halves. Much of it was a standard “boilerplate” Foreign Ministry overview of the state of the world. There was some hardening up of rhetoric with talk of “benign” becoming “malign” and old truths giving way to ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 day ago - NZ’s trans lobby is fighting a rearguard action

Graham Adams assesses the fallout of the Cass Review — The press release last Thursday from the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls didn’t make the mainstream news in New Zealand but it really should have. The startling title of Reem Alsalem’s statement — “Implementation of ‘Cass ...Point of OrderBy gadams10001 day ago

Graham Adams assesses the fallout of the Cass Review — The press release last Thursday from the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls didn’t make the mainstream news in New Zealand but it really should have. The startling title of Reem Alsalem’s statement — “Implementation of ‘Cass ...Point of OrderBy gadams10001 day ago - Your mandate is imaginary

This open-for-business, under-new-management cliché-pockmarked government of Christopher Luxon is not the thing of beauty he imagines it to be. It is not the powerful expression of the will of the people that he asserts it to be. It is not a soaring eagle, it is a malodorous vulture. This newest poll should make ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago

This open-for-business, under-new-management cliché-pockmarked government of Christopher Luxon is not the thing of beauty he imagines it to be. It is not the powerful expression of the will of the people that he asserts it to be. It is not a soaring eagle, it is a malodorous vulture. This newest poll should make ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago - 14,000 unemployed under National

The latest labour market statistics, showing a rise in unemployment. There are now 134,000 unemployed - 14,000 more than when the National government took office. Which is I guess what happens when the Reserve Bank causes a recession in an effort to Keep Wages Low. The previous government saw a ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago

The latest labour market statistics, showing a rise in unemployment. There are now 134,000 unemployed - 14,000 more than when the National government took office. Which is I guess what happens when the Reserve Bank causes a recession in an effort to Keep Wages Low. The previous government saw a ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago - Bryce Edwards: Discontent and gloom dominate NZ’s political mood

Three opinion polls have been released in the last two days, all showing that the new government is failing to hold their popular support. The usual honeymoon experienced during the first year of a first term government is entirely absent. The political mood is still gloomy and discontented, mainly due ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards2 days ago

Three opinion polls have been released in the last two days, all showing that the new government is failing to hold their popular support. The usual honeymoon experienced during the first year of a first term government is entirely absent. The political mood is still gloomy and discontented, mainly due ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards2 days ago - Taking Tea with 42 & 38.

National's Finance Minister once met a poor person.A scornful interview with National's finance guru who knows next to nothing about economics or people.There might have been something a bit familiar if that was the headline I’d gone with today. It would of course have been in tribute to the article ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago

National's Finance Minister once met a poor person.A scornful interview with National's finance guru who knows next to nothing about economics or people.There might have been something a bit familiar if that was the headline I’d gone with today. It would of course have been in tribute to the article ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago - Beware political propaganda: statistics are pointing to Grant Robertson never protecting “Lives an...

Rob MacCulloch writes – Throughout the pandemic, the new Vice-Chancellor-of-Otago-University-on-$629,000 per annum-Can-you-believe-it-and-Former-Finance-Minister Grant Robertson repeated the mantra over and over that he saved “lives and livelihoods”. As we update how this claim is faring over the course of time, the facts are increasingly speaking differently. NZ ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago

Rob MacCulloch writes – Throughout the pandemic, the new Vice-Chancellor-of-Otago-University-on-$629,000 per annum-Can-you-believe-it-and-Former-Finance-Minister Grant Robertson repeated the mantra over and over that he saved “lives and livelihoods”. As we update how this claim is faring over the course of time, the facts are increasingly speaking differently. NZ ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago - Winding back the hands of history’s clock

Chris Trotter writes – IT’S A COMMONPLACE of political speeches, especially those delivered in acknowledgement of electoral victory: “We’ll govern for all New Zealanders.” On the face of it, the pledge is a strange one. Why would any political leader govern in ways that advantaged the huge ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago

Chris Trotter writes – IT’S A COMMONPLACE of political speeches, especially those delivered in acknowledgement of electoral victory: “We’ll govern for all New Zealanders.” On the face of it, the pledge is a strange one. Why would any political leader govern in ways that advantaged the huge ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54432 days ago - Paula Bennett’s political appointment will challenge public confidence

Bryce Edwards writes – The list of former National Party Ministers being given plum and important roles got longer this week with the appointment of former Deputy Prime Minister Paula Bennett as the chair of Pharmac. The Christopher Luxon-led Government has now made key appointments to Bill ...Point of OrderBy xtrdnry2 days ago

Bryce Edwards writes – The list of former National Party Ministers being given plum and important roles got longer this week with the appointment of former Deputy Prime Minister Paula Bennett as the chair of Pharmac. The Christopher Luxon-led Government has now made key appointments to Bill ...Point of OrderBy xtrdnry2 days ago - Business confidence sliding into winter of discontent

TL;DR: These are the six things that stood out to me in news and commentary on Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy at 10:06am on Wednesday, May 1:The Lead: Business confidence fell across the board in April, falling in some areas to levels last seen during the lockdowns because of a collapse in ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

TL;DR: These are the six things that stood out to me in news and commentary on Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy at 10:06am on Wednesday, May 1:The Lead: Business confidence fell across the board in April, falling in some areas to levels last seen during the lockdowns because of a collapse in ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - Gordon Campbell on the coalition’s awful, not good, very bad poll results

Over the past 36 hours, Christopher Luxon has been dong his best to portray the centre-right’s plummeting poll numbers as a mark of virtue. Allegedly, the negative verdicts are the result of hard economic times, and of a government bravely set out on a perilous rescue mission from which not ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon2 days ago

Over the past 36 hours, Christopher Luxon has been dong his best to portray the centre-right’s plummeting poll numbers as a mark of virtue. Allegedly, the negative verdicts are the result of hard economic times, and of a government bravely set out on a perilous rescue mission from which not ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon2 days ago - New HOP readers for future payment options

Auckland Transport have started rolling out new HOP card readers around the network and over the next three months, all of them on buses, at train stations and ferry wharves will be replaced. The change itself is not that remarkable, with the new readers looking similar to what is already ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L2 days ago

Auckland Transport have started rolling out new HOP card readers around the network and over the next three months, all of them on buses, at train stations and ferry wharves will be replaced. The change itself is not that remarkable, with the new readers looking similar to what is already ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L2 days ago - 2024 Reading Summary: April (+ Writing Update)

Completed reads for April: The Difference Engine, by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling Carnival of Saints, by George Herman The Snow Spider, by Jenny Nimmo Emlyn’s Moon, by Jenny Nimmo The Chestnut Soldier, by Jenny Nimmo Death Comes As the End, by Agatha Christie Lord of the Flies, by ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2213 days ago

Completed reads for April: The Difference Engine, by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling Carnival of Saints, by George Herman The Snow Spider, by Jenny Nimmo Emlyn’s Moon, by Jenny Nimmo The Chestnut Soldier, by Jenny Nimmo Death Comes As the End, by Agatha Christie Lord of the Flies, by ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2213 days ago - At a glance – Clearing up misconceptions regarding 'hide the decline'

On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a ...3 days ago

On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a ...3 days ago - Road photos

Have a story to share about St Paul’s, but today just picturesPopular novels written at this desk by a young man who managed to bootstrap himself out of father’s imprisonment and his own young life in a workhouse Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago

Have a story to share about St Paul’s, but today just picturesPopular novels written at this desk by a young man who managed to bootstrap himself out of father’s imprisonment and his own young life in a workhouse Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago - Bryce Edwards: Paula Bennett’s political appointment will challenge public confidence

The list of former National Party Ministers being given plum and important roles got longer this week with the appointment of former Deputy Prime Minister Paula Bennett as the chair of Pharmac. The Christopher Luxon-led Government has now made key appointments to Bill English, Simon Bridges, Steven Joyce, Roger Sowry, ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards3 days ago

The list of former National Party Ministers being given plum and important roles got longer this week with the appointment of former Deputy Prime Minister Paula Bennett as the chair of Pharmac. The Christopher Luxon-led Government has now made key appointments to Bill English, Simon Bridges, Steven Joyce, Roger Sowry, ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards3 days ago - NZDF is still hostile to oversight

Newsroom has a story today about National's (fortunately failed) effort to disestablish the newly-created Inspector-General of Defence. The creation of this agency was the key recommendation of the Inquiry into Operation Burnham, and a vital means of restoring credibility and social licence to an agency which had been caught lying ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago

Newsroom has a story today about National's (fortunately failed) effort to disestablish the newly-created Inspector-General of Defence. The creation of this agency was the key recommendation of the Inquiry into Operation Burnham, and a vital means of restoring credibility and social licence to an agency which had been caught lying ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago - Winding Back The Hands Of History’s Clock.

Holding On To The Present: The moment a political movement arises that attacks the whole idea of social progress, and announces its intention to wind back the hands of History’s clock, then democracy, along with its unwritten rules, is in mortal danger.IT’S A COMMONPLACE of political speeches, especially those delivered in ...3 days ago

Holding On To The Present: The moment a political movement arises that attacks the whole idea of social progress, and announces its intention to wind back the hands of History’s clock, then democracy, along with its unwritten rules, is in mortal danger.IT’S A COMMONPLACE of political speeches, especially those delivered in ...3 days ago - Sweet Moderation? What Christopher Luxon Could Learn From The Germans.3 days ago

- A clear warning

The unpopular coalition government is currently rushing to repeal section 7AA of the Oranga Tamariki Act. The clause is Oranga Tamariki's Treaty clause, and was inserted after its systematic stealing of Māori children became a public scandal and resulted in physical resistance to further abductions. The clause created clear obligations ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago

The unpopular coalition government is currently rushing to repeal section 7AA of the Oranga Tamariki Act. The clause is Oranga Tamariki's Treaty clause, and was inserted after its systematic stealing of Māori children became a public scandal and resulted in physical resistance to further abductions. The clause created clear obligations ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant3 days ago - Poll results and Waitangi Tribunal report go unmentioned on the Beehive website – where racing tru...

Buzz from the Beehive The government’s official website – which Point of Order monitors daily – not for the first time has nothing much to say today about political happenings that are grabbing media headlines. It makes no mention of the latest 1News-Verian poll, for example. This shows National down ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin3 days ago

Buzz from the Beehive The government’s official website – which Point of Order monitors daily – not for the first time has nothing much to say today about political happenings that are grabbing media headlines. It makes no mention of the latest 1News-Verian poll, for example. This shows National down ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin3 days ago - Listening To The Traffic.3 days ago

- Comity Be Damned! The State’s Legislative Arm Is Flexing Its Constitutional Muscles.

Packing A Punch: The election of the present government, including in its ranks politicians dedicated to reasserting the rights of the legislature in shaping and determining the future of Māori and Pakeha in New Zealand, should have alerted the judiciary – including its anomalous appendage, the Waitangi Tribunal – that its ...3 days ago

Packing A Punch: The election of the present government, including in its ranks politicians dedicated to reasserting the rights of the legislature in shaping and determining the future of Māori and Pakeha in New Zealand, should have alerted the judiciary – including its anomalous appendage, the Waitangi Tribunal – that its ...3 days ago - Ending The Quest.

Dead Woman Walking: New Zealand’s media industry had been moving steadily towards disaster for all the years Melissa Lee had been National’s media and communications policy spokesperson, and yet, when the crisis finally broke, on her watch, she had nothing intelligent to offer. Christopher Luxon is a patient man - but he’s not ...3 days ago

Dead Woman Walking: New Zealand’s media industry had been moving steadily towards disaster for all the years Melissa Lee had been National’s media and communications policy spokesperson, and yet, when the crisis finally broke, on her watch, she had nothing intelligent to offer. Christopher Luxon is a patient man - but he’s not ...3 days ago - Will political polarisation intensify to the point where ‘normal’ government becomes impossible,...

Chris Trotter writes – New Zealand politics is remarkably easy-going: dangerously so, one might even say. With the notable exception of John Key’s flat ruling-out of the NZ First Party in 2008, all parties capable of clearing MMP’s five-percent threshold, or winning one or more electorate seats, tend ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54433 days ago

Chris Trotter writes – New Zealand politics is remarkably easy-going: dangerously so, one might even say. With the notable exception of John Key’s flat ruling-out of the NZ First Party in 2008, all parties capable of clearing MMP’s five-percent threshold, or winning one or more electorate seats, tend ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54433 days ago - Bernard’s pick 'n' mix for Tuesday, April 30

TL;DR: Here’s my top 10 ‘pick ‘n’ mix of links to news, analysis and opinion articles as of 10:30am on Tuesday, May 30:Scoop: NZ 'close to the tipping point' of measles epidemic, health experts warn NZ Herald Benjamin PlummerHealth: 'Absurd and totally unacceptable': Man has to wait a year for ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago

TL;DR: Here’s my top 10 ‘pick ‘n’ mix of links to news, analysis and opinion articles as of 10:30am on Tuesday, May 30:Scoop: NZ 'close to the tipping point' of measles epidemic, health experts warn NZ Herald Benjamin PlummerHealth: 'Absurd and totally unacceptable': Man has to wait a year for ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago - Why Tory Whanau has the lowest approval rating in the country

Bryce Edwards writes – Polling shows that Wellington Mayor Tory Whanau has the lowest approval rating of any mayor in the country. Siting at -12 per cent, the proportion of constituents who disapprove of her performance outweighs those who give her the thumbs up. This negative rating is ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54433 days ago

Bryce Edwards writes – Polling shows that Wellington Mayor Tory Whanau has the lowest approval rating of any mayor in the country. Siting at -12 per cent, the proportion of constituents who disapprove of her performance outweighs those who give her the thumbs up. This negative rating is ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54433 days ago - Worst poll result for a new Government in MMP historyThe KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago

- Pinning down climate change's role in extreme weather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler In the wake of any unusual weather event, someone inevitably asks, “Did climate change cause this?” In the most literal sense, that answer is almost always no. Climate change is never the sole cause of hurricanes, heat waves, droughts, or ...3 days ago

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler In the wake of any unusual weather event, someone inevitably asks, “Did climate change cause this?” In the most literal sense, that answer is almost always no. Climate change is never the sole cause of hurricanes, heat waves, droughts, or ...3 days ago - Serving at Seymour's pleasure.

Something odd happened yesterday, and I’d love to know if there’s more to it. If there was something which preempted what happened, or if it was simply a throwaway line in response to a journalist.Yesterday David Seymour was asked at a press conference what the process would be if the ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago

Something odd happened yesterday, and I’d love to know if there’s more to it. If there was something which preempted what happened, or if it was simply a throwaway line in response to a journalist.Yesterday David Seymour was asked at a press conference what the process would be if the ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago - Webworm LA Pop-Up

Hi,From time to time, I want to bring Webworm into the real world. We did it last year with the Jurassic Park event in New Zealand — which was a lot of fun!And so on Saturday May 11th, in Los Angeles, I am hosting a lil’ Webworm pop-up! I’ve been ...David FarrierBy David Farrier3 days ago

Hi,From time to time, I want to bring Webworm into the real world. We did it last year with the Jurassic Park event in New Zealand — which was a lot of fun!And so on Saturday May 11th, in Los Angeles, I am hosting a lil’ Webworm pop-up! I’ve been ...David FarrierBy David Farrier3 days ago - “Feel good” school is out

Education Minister Erica Standford yesterday unveiled a fundamental reform of the way our school pupils are taught. She would not exactly say so, but she is all but dismantling the so-called “inquiry” “feel good” method of teaching, which has ruled in our classrooms since a major review of the New ...PolitikBy Richard Harman3 days ago

Education Minister Erica Standford yesterday unveiled a fundamental reform of the way our school pupils are taught. She would not exactly say so, but she is all but dismantling the so-called “inquiry” “feel good” method of teaching, which has ruled in our classrooms since a major review of the New ...PolitikBy Richard Harman3 days ago - 6 Months in, surely our Report Card is “Ignored all warnings: recommend dismissal ASAP”?

Exactly where are we seriously going with this government and its policies? That is, apart from following what may as well be a Truss-Lite approach on the purported economic “plan“, and Victorian-era regression when it comes to social policy. Oh it’ll work this time of course, we’re basically assured, “the ...exhALANtBy exhalantblog3 days ago

Exactly where are we seriously going with this government and its policies? That is, apart from following what may as well be a Truss-Lite approach on the purported economic “plan“, and Victorian-era regression when it comes to social policy. Oh it’ll work this time of course, we’re basically assured, “the ...exhALANtBy exhalantblog3 days ago - Bread, and how it gets buttered

Hey Uncle Dave, When the Poms joined the EEC, I wasn't one of those defeatists who said, Well, that’s it for the dairy job. And I was right, eh? The Chinese can’t get enough of our milk powder and eventually, the Poms came to their senses and backed up the ute ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack4 days ago

Hey Uncle Dave, When the Poms joined the EEC, I wasn't one of those defeatists who said, Well, that’s it for the dairy job. And I was right, eh? The Chinese can’t get enough of our milk powder and eventually, the Poms came to their senses and backed up the ute ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack4 days ago - Bryce Edwards: Why Tory Whanau has the lowest approval rating in the country

Polling shows that Wellington Mayor Tory Whanau has the lowest approval rating of any mayor in the country. Siting at -12 per cent, the proportion of constituents who disapprove of her performance outweighs those who give her the thumbs up. This negative rating is higher than for any other mayor ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards4 days ago

Polling shows that Wellington Mayor Tory Whanau has the lowest approval rating of any mayor in the country. Siting at -12 per cent, the proportion of constituents who disapprove of her performance outweighs those who give her the thumbs up. This negative rating is higher than for any other mayor ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards4 days ago - Justice for Gaza?

The New York Times reports that the International Criminal Court is about to issue arrest warrants for Israeli officials, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, over their genocide in Gaza: Israeli officials increasingly believe that the International Criminal Court is preparing to issue arrest warrants for senior government officials on ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant4 days ago

The New York Times reports that the International Criminal Court is about to issue arrest warrants for Israeli officials, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, over their genocide in Gaza: Israeli officials increasingly believe that the International Criminal Court is preparing to issue arrest warrants for senior government officials on ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant4 days ago - If there has been any fiddling with Pharmac’s funding, we can count on Paula to figure out the fis...

Buzz from the Beehive Pharmac has been given a financial transfusion and a new chair to oversee its spending in the pharmaceutical business. Associate Health Minister David Seymour described the funding for Pharmac as “its largest ever budget of $6.294 billion over four years, fixing a $1.774 billion fiscal cliff”. ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin4 days ago

Buzz from the Beehive Pharmac has been given a financial transfusion and a new chair to oversee its spending in the pharmaceutical business. Associate Health Minister David Seymour described the funding for Pharmac as “its largest ever budget of $6.294 billion over four years, fixing a $1.774 billion fiscal cliff”. ...Point of OrderBy Bob Edlin4 days ago - FastTrackWatch – The case for the Government’s Fast Track Bill

Bryce Edwards writes – Many criticisms are being made of the Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill, including by this writer. But as with everything in politics, every story has two sides, and both deserve attention. It’s important to understand what the Government is trying to achieve and its ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago

Bryce Edwards writes – Many criticisms are being made of the Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill, including by this writer. But as with everything in politics, every story has two sides, and both deserve attention. It’s important to understand what the Government is trying to achieve and its ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54434 days ago - Bernard’s pick 'n' mix for Monday, April 29

TL;DR: Here’s my top 10 ‘pick ‘n’ mix of links to news, analysis and opinion articles as of 10:10am on Monday, April 29:Scoop: The children's ward at Rotorua Hospital will be missing a third of its beds as winter hits because Te Whatu Ora halted an upgrade partway through to ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

TL;DR: Here’s my top 10 ‘pick ‘n’ mix of links to news, analysis and opinion articles as of 10:10am on Monday, April 29:Scoop: The children's ward at Rotorua Hospital will be missing a third of its beds as winter hits because Te Whatu Ora halted an upgrade partway through to ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - Gordon Campbell on Iran killing its rappers, and searching for the invisible Dr. Reti

span class=”dropcap”>As hideous as David Seymour can be, it is worth keeping in mind occasionally that there are even worse political figures (and regimes) out there. Iran for instance, is about to execute the country’s leading hip hop musician Toomaj Salehi, for writing and performing raps that “corrupt” the nation’s ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon4 days ago

span class=”dropcap”>As hideous as David Seymour can be, it is worth keeping in mind occasionally that there are even worse political figures (and regimes) out there. Iran for instance, is about to execute the country’s leading hip hop musician Toomaj Salehi, for writing and performing raps that “corrupt” the nation’s ...Gordon CampbellBy lyndon4 days ago - Auckland Rail Electrification 10 years old

Yesterday marked 10 years since the first electric train carried passengers in Auckland so it’s a good time to look back at it and the impact it has had. A brief history The first proposals for rail electrification in Auckland came in the 1920’s alongside the plans for earlier ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L4 days ago

Yesterday marked 10 years since the first electric train carried passengers in Auckland so it’s a good time to look back at it and the impact it has had. A brief history The first proposals for rail electrification in Auckland came in the 1920’s alongside the plans for earlier ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L4 days ago - Coalition's dirge of austerity and uncertainty is driving the economy into a deeper recessionThe KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

- Disability Funding or Tax Cuts.

You make people evil to punish the paststuck inside a sequel with a rotating castThe following photos haven’t been generated with AI, or modified in any way. They are flesh and blood, human beings. On the left is Galatea Young, a young mum, and her daughter Fiadh who has Angelman ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago

You make people evil to punish the paststuck inside a sequel with a rotating castThe following photos haven’t been generated with AI, or modified in any way. They are flesh and blood, human beings. On the left is Galatea Young, a young mum, and her daughter Fiadh who has Angelman ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago - Of the Goodness of Tolkien’s Eru

April has been a quiet month at A Phuulish Fellow. I have had an exceptionally good reading month, and a decently productive writing month – for original fiction, anyway – but not much has caught my eye that suggested a blog article. It has been vaguely frustrating, to be honest. ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2214 days ago

April has been a quiet month at A Phuulish Fellow. I have had an exceptionally good reading month, and a decently productive writing month – for original fiction, anyway – but not much has caught my eye that suggested a blog article. It has been vaguely frustrating, to be honest. ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2214 days ago - 2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #17

A listing of 31 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, April 21, 2024 thru Sat, April 27, 2024. Story of the week Anthropogenic climate change may be the ultimate shaggy dog story— but with a twist, because here ...5 days ago

A listing of 31 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, April 21, 2024 thru Sat, April 27, 2024. Story of the week Anthropogenic climate change may be the ultimate shaggy dog story— but with a twist, because here ...5 days ago - Pastor Who Abused People, Blames People

Hi,I spent about a year on Webworm reporting on an abusive megachurch called Arise, and it made me want to stab my eyes out with a fork.I don’t regret that reporting in 2022 and 2023 — I am proud of it — but it made me angry.Over three main stories ...David FarrierBy David Farrier5 days ago

Hi,I spent about a year on Webworm reporting on an abusive megachurch called Arise, and it made me want to stab my eyes out with a fork.I don’t regret that reporting in 2022 and 2023 — I am proud of it — but it made me angry.Over three main stories ...David FarrierBy David Farrier5 days ago - Vic Uni shows how under threat free speech is

The new Victoria University Vice-Chancellor decided to have a forum at the university about free speech and academic freedom as it is obviously a topical issue, and the Government is looking at legislating some carrots or sticks for universities to uphold their obligations under the Education and Training Act. They ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54435 days ago

The new Victoria University Vice-Chancellor decided to have a forum at the university about free speech and academic freedom as it is obviously a topical issue, and the Government is looking at legislating some carrots or sticks for universities to uphold their obligations under the Education and Training Act. They ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54435 days ago - Winston remembers Gettysburg.

Do you remember when Melania Trump got caught out using a speech that sounded awfully like one Michelle Obama had given? Uncannily so.Well it turns out that Abraham Lincoln is to Winston Peters as Michelle was to Melania. With the ANZAC speech Uncle Winston gave at Gallipoli having much in ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago

Do you remember when Melania Trump got caught out using a speech that sounded awfully like one Michelle Obama had given? Uncannily so.Well it turns out that Abraham Lincoln is to Winston Peters as Michelle was to Melania. With the ANZAC speech Uncle Winston gave at Gallipoli having much in ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago - 25

She was born 25 years ago today in North Shore hospital. Her eyes were closed tightly shut, her mouth was silently moving. The whole theatre was all quiet intensity as they marked her a 2 on the APGAR test. A one-minute eternity later, she was an 8. The universe was ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack5 days ago

She was born 25 years ago today in North Shore hospital. Her eyes were closed tightly shut, her mouth was silently moving. The whole theatre was all quiet intensity as they marked her a 2 on the APGAR test. A one-minute eternity later, she was an 8. The universe was ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack5 days ago - Fact Brief – Is Antarctica gaining land ice?

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park in collaboration with members from our Skeptical Science team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Is Antarctica gaining land ice? ...6 days ago

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park in collaboration with members from our Skeptical Science team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Is Antarctica gaining land ice? ...6 days ago - Policing protests.

Images of US students (and others) protesting and setting up tent cities on US university campuses have been broadcast world wide and clearly demonstrate the growing rifts in US society caused by US policy toward Israel and Israel’s prosecution of … Continue reading → ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo6 days ago

Images of US students (and others) protesting and setting up tent cities on US university campuses have been broadcast world wide and clearly demonstrate the growing rifts in US society caused by US policy toward Israel and Israel’s prosecution of … Continue reading → ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo6 days ago - Open letter to Hon Paul Goldsmith

Barrie Saunders writes – Dear Paul As the new Minister of Media and Communications, you will be inundated with heaps of free advice and special pleading, all in the national interest of course. For what it’s worth here is my assessment: Traditional broadcasting free to air content through ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54436 days ago

Barrie Saunders writes – Dear Paul As the new Minister of Media and Communications, you will be inundated with heaps of free advice and special pleading, all in the national interest of course. For what it’s worth here is my assessment: Traditional broadcasting free to air content through ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54436 days ago - Bryce Edwards: FastTrackWatch – The Case for the Government’s Fast Track Bill

Many criticisms are being made of the Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill, including by this writer. But as with everything in politics, every story has two sides, and both deserve attention. It’s important to understand what the Government is trying to achieve and its arguments for such a bold reform. ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards6 days ago

Many criticisms are being made of the Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill, including by this writer. But as with everything in politics, every story has two sides, and both deserve attention. It’s important to understand what the Government is trying to achieve and its arguments for such a bold reform. ...Democracy ProjectBy bryce.edwards6 days ago - Luxon gets out his butcher’s knife – briefly

Peter Dunne writes – The great nineteenth British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, once observed that “the first essential for a Prime Minister is to be a good butcher.” When a later British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, sacked a third of his Cabinet in July 1962, in what became ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54436 days ago

Peter Dunne writes – The great nineteenth British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, once observed that “the first essential for a Prime Minister is to be a good butcher.” When a later British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, sacked a third of his Cabinet in July 1962, in what became ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54436 days ago - More tax for less

Ele Ludemann writes – New Zealanders had the OECD’s second highest tax increase last year: New Zealanders faced the second-biggest tax raises in the developed world last year, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) says. The intergovernmental agency said the average change in personal income tax ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54436 days ago

Ele Ludemann writes – New Zealanders had the OECD’s second highest tax increase last year: New Zealanders faced the second-biggest tax raises in the developed world last year, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) says. The intergovernmental agency said the average change in personal income tax ...Point of OrderBy poonzteam54436 days ago - Real News vs Fake News.

We all know something’s not right with our elections. The spread of misinformation, people being targeted with soundbites and emotional triggers that ignore the facts, even the truth, and influence their votes.The use of technology to produce deep fakes. How can you tell if something is real or not? Can ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel6 days ago

We all know something’s not right with our elections. The spread of misinformation, people being targeted with soundbites and emotional triggers that ignore the facts, even the truth, and influence their votes.The use of technology to produce deep fakes. How can you tell if something is real or not? Can ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel6 days ago - Another way to roll

Hello! Here comes the Saturday edition of More Than A Feilding, catching you up on the past week’s editions.Share ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack6 days ago

Hello! Here comes the Saturday edition of More Than A Feilding, catching you up on the past week’s editions.Share ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack6 days ago - Simon Clark: The climate lies you'll hear this year

This video includes conclusions of the creator climate scientist Dr. Simon Clark. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any). This year you will be lied to! Simon Clark helps prebunk some misleading statements you'll hear about climate. The video includes ...6 days ago

This video includes conclusions of the creator climate scientist Dr. Simon Clark. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any). This year you will be lied to! Simon Clark helps prebunk some misleading statements you'll hear about climate. The video includes ...6 days ago - Cutting the Public Service

It is all very well cutting the backrooms of public agencies but it may compromise the frontlines. One of the frustrations of the Productivity Commission’s 2017 review of universities is that while it observed that their non-academic staff were increasing faster than their academic staff, it did not bother to ...PunditBy Brian Easton7 days ago

It is all very well cutting the backrooms of public agencies but it may compromise the frontlines. One of the frustrations of the Productivity Commission’s 2017 review of universities is that while it observed that their non-academic staff were increasing faster than their academic staff, it did not bother to ...PunditBy Brian Easton7 days ago

Related Posts

- Release: National gaslights women fighting for equal pay

National has scrapped the pay equity taskforce that fights for equal pay for women and looks at ethnic pay gaps. ...15 hours ago

National has scrapped the pay equity taskforce that fights for equal pay for women and looks at ethnic pay gaps. ...15 hours ago - Release: More job cuts, fewer houses under National

The Government is again adding to New Zealand’s growing unemployment, this time cutting jobs at the agencies responsible for urban development and growing much needed housing stock. ...15 hours ago

The Government is again adding to New Zealand’s growing unemployment, this time cutting jobs at the agencies responsible for urban development and growing much needed housing stock. ...15 hours ago - Release: Children fall deeper through the cracks in Govt cuts

With Minister Karen Chhour indicating in the House today that she either doesn’t know or care about the frontline cuts she’s making to Oranga Tamariki, we risk seeing more and more of our children falling through the cracks. ...17 hours ago

With Minister Karen Chhour indicating in the House today that she either doesn’t know or care about the frontline cuts she’s making to Oranga Tamariki, we risk seeing more and more of our children falling through the cracks. ...17 hours ago - Release: Labour honours memory of Sir Robert Martin

The Labour Party is saddened to learn of the death of Sir Robert Martin, a globally renowned disability advocate who led the way for disability rights both in New Zealand and internationally. ...23 hours ago

The Labour Party is saddened to learn of the death of Sir Robert Martin, a globally renowned disability advocate who led the way for disability rights both in New Zealand and internationally. ...23 hours ago - Release: 130,000 cattle saved from live export

Labour is calling for the Government to urgently rethink its coalition commitment to restart live animal exports, Labour animal welfare spokesperson Rachel Boyack said. ...2 days ago

Labour is calling for the Government to urgently rethink its coalition commitment to restart live animal exports, Labour animal welfare spokesperson Rachel Boyack said. ...2 days ago - Central Bank makes clear Government is pouring fuel on housing crisis fire

Today’s Financial Stability Report has once again highlighted that poverty and deep inequality are political choices - and this Government is choosing to make them worse. ...2 days ago

Today’s Financial Stability Report has once again highlighted that poverty and deep inequality are political choices - and this Government is choosing to make them worse. ...2 days ago - New unemployment figures paint bleak picture

The Green Party is calling on the Government to do more for our households in most need as unemployment rises and the cost of living crisis endures. ...2 days ago

The Green Party is calling on the Government to do more for our households in most need as unemployment rises and the cost of living crisis endures. ...2 days ago - Release: National’s job cuts already starting to bite as unemployment rises

Unemployment is on the rise and it’s only going to get worse under this Government, Labour finance spokesperson Barbara Edmonds said. Stats NZ figures show the unemployment rate grew to 4.3 percent in the March quarter from 4 percent in the December quarter. “This is the second rise in unemployment ...2 days ago

Unemployment is on the rise and it’s only going to get worse under this Government, Labour finance spokesperson Barbara Edmonds said. Stats NZ figures show the unemployment rate grew to 4.3 percent in the March quarter from 4 percent in the December quarter. “This is the second rise in unemployment ...2 days ago - Release: National hiking transport costs for families and young New Zealanders

Weekly expenses will grow for more than 1.6 million New Zealanders as the Government ends free and half price public transport fares tomorrow. ...3 days ago

Weekly expenses will grow for more than 1.6 million New Zealanders as the Government ends free and half price public transport fares tomorrow. ...3 days ago - Release: Labour welcomes EU free trade agreement

The New Zealand Labour Party welcomes the entering into force of the European Union and New Zealand free trade agreement. This agreement opens the door for a huge increase in trade opportunities with a market of 450 million people who are high value discerning consumers of New Zealand goods and ...3 days ago

The New Zealand Labour Party welcomes the entering into force of the European Union and New Zealand free trade agreement. This agreement opens the door for a huge increase in trade opportunities with a market of 450 million people who are high value discerning consumers of New Zealand goods and ...3 days ago - Surprise: Landlord tax cuts don’t trickle down

The Green Party is renewing its call for rent controls following reports of rental prices hitting an all-time high. ...3 days ago

The Green Party is renewing its call for rent controls following reports of rental prices hitting an all-time high. ...3 days ago - Release: $1.7b for no increase in access to medicine

The National-led Government continues its fiscal jiggery pokery with its Pharmac announcement today, Labour Health spokesperson Ayesha Verrall says. “The government has increased Pharmac funding but conceded it will only make minimal increases in access to medicine”, said Ayesha Verrall “This is far from the bold promises made to fund ...3 days ago

The National-led Government continues its fiscal jiggery pokery with its Pharmac announcement today, Labour Health spokesperson Ayesha Verrall says. “The government has increased Pharmac funding but conceded it will only make minimal increases in access to medicine”, said Ayesha Verrall “This is far from the bold promises made to fund ...3 days ago - Release: National should heed Tribunal warning and scrap coalition commitment with ACT

This afternoon’s interim Waitangi Tribunal report must be taken seriously as it affects our most vulnerable children, Labour children’s spokesperson Willow-Jean Prime. ...4 days ago

This afternoon’s interim Waitangi Tribunal report must be taken seriously as it affects our most vulnerable children, Labour children’s spokesperson Willow-Jean Prime. ...4 days ago - Release: More accountability for preventable workplace deaths this Workers’ Memorial Day

Labour is calling for more accountability for preventable workplace deaths because everybody who goes to work deserves to come home safely. ...4 days ago

Labour is calling for more accountability for preventable workplace deaths because everybody who goes to work deserves to come home safely. ...4 days ago - Gaza: Aotearoa Must Support Independent Investigation into Mass Graves

Te Pāti Māori are demanding the New Zealand Government support an international independent investigation into mass graves that have been uncovered at two hospitals on the Gaza strip, following weeks of assault by Israeli troops. Among the 392 bodies that have been recovered, are children and elderly civilians. Many of ...7 days ago

Te Pāti Māori are demanding the New Zealand Government support an international independent investigation into mass graves that have been uncovered at two hospitals on the Gaza strip, following weeks of assault by Israeli troops. Among the 392 bodies that have been recovered, are children and elderly civilians. Many of ...7 days ago - Release: Working together on consistent support for veterans this Anzac Day

Our two-tiered system for veterans’ support is out of step with our closest partners, and all parties in Parliament should work together to fix it, Labour veterans’ affairs spokesperson Greg O’Connor said. ...1 week ago

Our two-tiered system for veterans’ support is out of step with our closest partners, and all parties in Parliament should work together to fix it, Labour veterans’ affairs spokesperson Greg O’Connor said. ...1 week ago - Release: Penny drops – but what about Seymour and Peters?

Stripping two Ministers of their portfolios just six months into the job shows Christopher Luxon’s management style is lacking, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said. ...1 week ago

Stripping two Ministers of their portfolios just six months into the job shows Christopher Luxon’s management style is lacking, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said. ...1 week ago - Another ‘Stolen Generation’ enabled by court ruling on Waitangi Tribunal summons

Tonight’s court decision to overturn the summons of the Children’s Minister has enabled the Crown to continue making decisions about Māori without evidence, says Te Pāti Māori spokesperson for Children, Mariameno Kapa-Kingi. “The judicial system has this evening told the nation that this government can do whatever they want when ...1 week ago

Tonight’s court decision to overturn the summons of the Children’s Minister has enabled the Crown to continue making decisions about Māori without evidence, says Te Pāti Māori spokesperson for Children, Mariameno Kapa-Kingi. “The judicial system has this evening told the nation that this government can do whatever they want when ...1 week ago - Release: Budget blunder shows Nicola Willis could cut recovery funding

It appears Nicola Willis is about to pull the rug out from under the feet of local communities still dealing with the aftermath of last year’s severe weather, and local councils relying on funding to build back from these disasters. ...1 week ago

It appears Nicola Willis is about to pull the rug out from under the feet of local communities still dealing with the aftermath of last year’s severe weather, and local councils relying on funding to build back from these disasters. ...1 week ago - Further environmental mismanagement on the cards

The Government’s resource management reforms will add to the heavy and ever-growing burden this Government is loading on to our environment. ...1 week ago

The Government’s resource management reforms will add to the heavy and ever-growing burden this Government is loading on to our environment. ...1 week ago - Release: RMA changes will be a disaster for environment

The Government is making short-sighted changes to the Resource Management Act (RMA) that will take away environmental protection in favour of short-term profits, Labour’s environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said today. ...1 week ago

The Government is making short-sighted changes to the Resource Management Act (RMA) that will take away environmental protection in favour of short-term profits, Labour’s environment spokesperson Rachel Brooking said today. ...1 week ago - Release: Labour supports urgent changes to emergency management system

Labour welcomes the release of the report into the North Island weather events and looks forward to working with the Government to ensure that New Zealand is as prepared as it can be for the next natural disaster. ...1 week ago

Labour welcomes the release of the report into the North Island weather events and looks forward to working with the Government to ensure that New Zealand is as prepared as it can be for the next natural disaster. ...1 week ago - Release: Labour calls for New Zealand to recognise Palestine

The Labour Party has called for the New Zealand Government to recognise Palestine, as a material step towards progressing the two-State solution needed to achieve a lasting peace in the region. ...2 weeks ago

The Labour Party has called for the New Zealand Government to recognise Palestine, as a material step towards progressing the two-State solution needed to achieve a lasting peace in the region. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Three strikes law political posturing of worst kind

The Government is bringing back a law that has little evidential backing just to look tough, Labour justice spokesperson Duncan Webb said. ...2 weeks ago

The Government is bringing back a law that has little evidential backing just to look tough, Labour justice spokesperson Duncan Webb said. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Government cuts unbelievably target child exploitation, violent extremism, ports and airpor...

Some of our country’s most important work, stopping the sexual exploitation of children and violent extremism could go along with staff on the frontline at ports and airports. ...2 weeks ago

Some of our country’s most important work, stopping the sexual exploitation of children and violent extremism could go along with staff on the frontline at ports and airports. ...2 weeks ago - Three strikes has failed before and will fail again

Resurrecting the archaic three-strikes legislation is an unwelcome return to a failed American-style approach to justice. ...2 weeks ago

Resurrecting the archaic three-strikes legislation is an unwelcome return to a failed American-style approach to justice. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Environmental protection vital, not ‘onerous’

The Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill will give projects such as new coal mines a ‘get out of jail free’ card to wreak havoc on the environment, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said today. ...2 weeks ago

The Government’s Fast Track Approvals Bill will give projects such as new coal mines a ‘get out of jail free’ card to wreak havoc on the environment, Labour Leader Chris Hipkins said today. ...2 weeks ago - Ferris – Three Strikes targets those ‘too brown to be white’

The government's decision to reintroduce Three Strikes is a destructive and ineffective piece of law-making that will only exacerbate an inherently biased and racist criminal justice system, said Te Pāti Māori Justice Spokesperson, Tākuta Ferris, today. During the time Three Strikes was in place in Aotearoa, Māori and Pasifika received ...2 weeks ago

The government's decision to reintroduce Three Strikes is a destructive and ineffective piece of law-making that will only exacerbate an inherently biased and racist criminal justice system, said Te Pāti Māori Justice Spokesperson, Tākuta Ferris, today. During the time Three Strikes was in place in Aotearoa, Māori and Pasifika received ...2 weeks ago - Release: Govt cuts doctors and nurses in hiring freeze

Cuts to frontline hospital staff are not only a broken election promise, it shows the reckless tax cuts have well and truly hit the frontline of the health system, says Labour Health spokesperson Ayesha Verrall. ...2 weeks ago

Cuts to frontline hospital staff are not only a broken election promise, it shows the reckless tax cuts have well and truly hit the frontline of the health system, says Labour Health spokesperson Ayesha Verrall. ...2 weeks ago - Fast-track submissions period must be extended

The Green Party has joined the call for public submissions on the fast-track legislation to be extended after the Ombudsman forced the Government to release the list of organisations invited to apply just hours before submissions close. ...2 weeks ago

The Green Party has joined the call for public submissions on the fast-track legislation to be extended after the Ombudsman forced the Government to release the list of organisations invited to apply just hours before submissions close. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Progress on climate will be undone by Govt

New Zealand’s good work at reducing climate emissions for three years in a row will be undone by the National government’s lack of ambition and scrapping programmes that were making a difference, Labour Party climate spokesperson Megan Woods said today. ...2 weeks ago

New Zealand’s good work at reducing climate emissions for three years in a row will be undone by the National government’s lack of ambition and scrapping programmes that were making a difference, Labour Party climate spokesperson Megan Woods said today. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Dark day for Kiwi kids as a third of Govt cuts affect them

News that 1000 jobs at the Ministry of Education and Oranga Tamariki could go is devastating for future generations of New Zealanders. ...2 weeks ago

News that 1000 jobs at the Ministry of Education and Oranga Tamariki could go is devastating for future generations of New Zealanders. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Alarm as Government signals further blow to school lunches

More essential jobs could be on the chopping block, this time Ministry of Education staff on the school lunches team are set to find out whether they're in line to lose their jobs. ...2 weeks ago