Remembering the 5th of November and Parihaka

Remembering the 5th of November and Parihaka

Written By:

notices and features - Date published:

2:44 pm, November 5th, 2019 - 9 comments

Categories: Maori Issues -

Tags: J.C. Sturm, parihaka, Parihaka Reconciliation Bill

It didn't matter that Māori did.

— @br3nda@cloudisland.nz (@BR3NDA) November 4, 2019

Fight back, not fight, sell some, become Christian, become capitalists, farm their land, trade… The crown and Pākehā settlers wanted it, & used the most violent of methods to get. Destroying food sources, disease, and with muskets and canons.

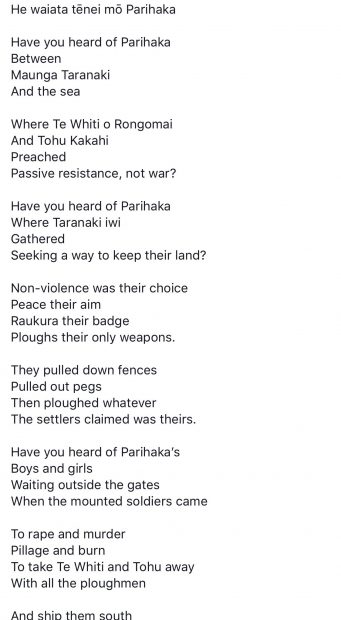

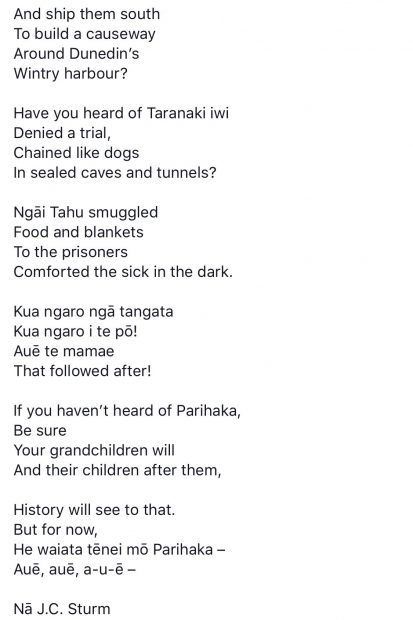

Jack McDonald posted this poem by his Nana, J.C. Sturm, to mark the anniversary of the invasion of Parihaka in 1881.

Dylan Owen at the National Library writes,

Remembering Parihaka

Many New Zealanders associate 5 November with Guy Fawkes and an evening of family fun and fireworks. But some Māori remember the date for a very different reason.

For Taranaki Māori, 5 November 1881 is known as ‘Te Rā o te Pāhua’ or ‘The Day of Plunder’. The invasion of Parihaka — te pāhuatanga — happened when around 1500 armed constabulary and volunteers led by the Native Affairs Minister, John Bryce, invaded Parihaka.

For months leading up to the invasion, troops had surrounded the peaceful Taranaki Māori village. They even set up a cannon on a nearby hill. While the soldiers had enough ammunition and rations to see them through a ‘bloody battle’, the reality was very different.

There was no bloody fighting. Instead, soldiers entering the village were greeted by singing children and women offering them fresh loaves of bread.

What happened?

It made no difference.

Following the invasion of Parihaka, its leaders, Tohu Kakahi and Te Whiti o Rongomai, were arrested and imprisoned without trial. Sixteen hundred followers were expelled, while buildings and crops were plundered and destroyed by the Pakeha troops.

In 1903, journalist William Baucke met Te Whiti and wrote down his thoughts on the events that led up to the sacking of Parihaka. Te Whiti told him:

‘The white man in his covetousness ordered me to move on instead of removing himself from my presence. I resisted; I resist to this day’… suddenly he (Te Whiti) pointed to the mountain. ‘Ask that mountain,’ he said, ‘Taranaki saw it all!’

— ‘Ask that Mountain: The Story of Parihaka’ by Dick Scott. Raupo, 2008, p.186–187.Reconciliation

In 2017, over 100 years later, the Crown was again met with singing children and food baskets at Parihaka. This time the circumstances were very different.

The Crown was there to deliver te whakapāha — a formal apology for its actions over Parihaka.

Hundreds attended He Puanga Haeata — the reconciliation ceremony. Some openly wept as Treaty Negotiations Minister Chris Finlayson delivered the Government apology.

‘That is why the Crown comes today offering an apology to the people of Parihaka for actions that were committed in its name almost 140 years ago.’

‘… Parihaka has waited a long time for this day,’ Finlayson also added.

Te Pire Haeata ki Parihaka (Parihaka Reconciliation Bill)

The Crown acknowledges that it utterly failed to recognise or respect the vision of self-determination and partnership that Parihaka represented. The Crown responded to peace with tyranny, to unity with division, and to autonomy with oppression.

On 24 October 2019, the apology or Te Pire Haeata ki Parihaka (Parihaka Reconciliation Bill) was finally passed into law.

Korero, waiata, and tears — it was an extraordinarily emotional day for politicians and the 100 or so people who had travelled from Parihaka to Parliament to witness the occasion.

Next steps

The Reconciliation Bill also included:

• the establishment of a Parihaka–Crown Leaders’ Forum

• Te Huanga o Rongo — healing and reconciliation assistance

• the setting up of a Parihaka fund

• protection of the name ‘Parihaka’ from commercial use.At Parliament for the Bill’s final reading, Puna Wano-Bryant (Parihaka’s Papakainga Trust chair) also noted that the teaching of Aotearoa New Zealand history in all our schools was an important next step.

We want our children to not only talk about the facts of history but also about the pain and injury that has caused and that how we move forward as a nation together — Māori and Pākehā.

Full post by Dylan Owen is here. Republished from the National Library website under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 New Zealand licence.

Related Posts

9 comments on “Remembering the 5th of November and Parihaka ”

- Comments are now closed

- Comments are now closed

Recent Comments

- Jenny on

- Res Publica to Ad on

- Jenny to James Simpson on

- tWig on

- Jenny to James Thrace on

- Incognito to Higherstandard on

- Higherstandard to Martin Judd on

- joe90 on

- Jilly Bee on

- CharlieB on

- Stephen D on

- KJT to Higherstandard on

- Martin Judd to Higherstandard on

- Macro on

- adam on

- Wynston on

- SPC on

- adam on

- adam on

- SPC on

- SPC on

- Hunter Thompson II to Adrian on

- Barfly to James Simpson on

- Patricia Bremner to Adrian on

- weka to Belladonna on

- gsays to James Simpson on

- SPC on

- Incognito to Belladonna on

- SPC on

- Mikey on

- Incognito on

- Adrian on

- Adrian on

- George.com to Patricia Bremner on

- mpledger to Patricia Bremner on

- Bearded Git to Joe90 on

- Tony Veitch to Patricia Bremner on

Recent Posts

-

by Mike Smith

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mike Smith

-

by Incognito

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by Mike Smith

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by advantage

-

by lprent

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by weka

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

- Dragging our way towards the finish line, the end of this year can’t come soon enough for many…

Similar to the cuts and the austerity drive imposed by Ruth Richardson in the 1990’s, an era which to all intents and purposes we’ve largely fiddled around the edges with fixing in the time since – over, to be fair, several administrations – whilst trying our best it seems to ...exhALANtBy exhalantblog10 hours ago

Similar to the cuts and the austerity drive imposed by Ruth Richardson in the 1990’s, an era which to all intents and purposes we’ve largely fiddled around the edges with fixing in the time since – over, to be fair, several administrations – whilst trying our best it seems to ...exhALANtBy exhalantblog10 hours ago - Handling Democracy.

String-Pulling in the Dark: For the democratic process to be meaningful it must also be public. WITH TRUST AND CONFIDENCE in New Zealand’s politicians and journalists steadily declining, restoring those virtues poses a daunting challenge. Just how daunting is made clear by comparing the way politicians and journalists treated New Zealanders ...11 hours ago

String-Pulling in the Dark: For the democratic process to be meaningful it must also be public. WITH TRUST AND CONFIDENCE in New Zealand’s politicians and journalists steadily declining, restoring those virtues poses a daunting challenge. Just how daunting is made clear by comparing the way politicians and journalists treated New Zealanders ...11 hours ago - Open letter to the Minister of Dwindling Finances

Dear Nicola Willis, thank you for letting us know in so many words that the swingeing austerity hasn't worked.By in so many words I mean the bit where you said, Here is a sea of red ink in which we are drowning after twelve months of savage cost cutting and ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack13 hours ago

Dear Nicola Willis, thank you for letting us know in so many words that the swingeing austerity hasn't worked.By in so many words I mean the bit where you said, Here is a sea of red ink in which we are drowning after twelve months of savage cost cutting and ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack13 hours ago - Open Government: The joke ends

The Open Government Partnership is a multilateral organisation committed to advancing open government. Countries which join are supposed to co-create regular action plans with civil society, committing to making verifiable improvements in transparency, accountability, participation, or technology and innovation for the above. And they're held to account through an Independent ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant13 hours ago

The Open Government Partnership is a multilateral organisation committed to advancing open government. Countries which join are supposed to co-create regular action plans with civil society, committing to making verifiable improvements in transparency, accountability, participation, or technology and innovation for the above. And they're held to account through an Independent ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant13 hours ago - An unusual sort of press conference

Today I tuned into something strange: a press conference that didn’t make my stomach churn or the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. Which was strange, because it was about the torture of children. It was the announcement by Erica Stanford — on her own, unusually ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi14 hours ago

Today I tuned into something strange: a press conference that didn’t make my stomach churn or the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. Which was strange, because it was about the torture of children. It was the announcement by Erica Stanford — on her own, unusually ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi14 hours ago - This substack has talked about this government’s seeming corruption & pro-corporate issues...

This is a must watch, and puts on brilliant and practical display the implications and mechanics of fast-track law corruption and weakness.CLICK HERE: LINK TO WATCH VIDEOOur news media as it is set up is simply not equipped to deal with the brazen disinformation and corruption under this right wing ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī14 hours ago

This is a must watch, and puts on brilliant and practical display the implications and mechanics of fast-track law corruption and weakness.CLICK HERE: LINK TO WATCH VIDEOOur news media as it is set up is simply not equipped to deal with the brazen disinformation and corruption under this right wing ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī14 hours ago - NZCTU: Minister needs to listen to the evidence on engineered stone ban

NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi Acting Secretary Erin Polaczuk is welcoming the announcement from Minister of Workplace Relations and Safety Brooke van Velden that she is opening consultation on engineered stone and is calling on her to listen to the evidence and implement a total ban of the product. “We need ...NZCTUBy Stella Whitfield14 hours ago

NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi Acting Secretary Erin Polaczuk is welcoming the announcement from Minister of Workplace Relations and Safety Brooke van Velden that she is opening consultation on engineered stone and is calling on her to listen to the evidence and implement a total ban of the product. “We need ...NZCTUBy Stella Whitfield14 hours ago - Wednesday 18 December

The Government has announced a 1.5% increase in the minimum wage from 1 April 2025, well below forecast inflation of 2.5%. Unions have reacted strongly and denounced it as a real terms cut. PSA and the CTU are opposing a new round of staff cuts at WorkSafe, which they say ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald15 hours ago

The Government has announced a 1.5% increase in the minimum wage from 1 April 2025, well below forecast inflation of 2.5%. Unions have reacted strongly and denounced it as a real terms cut. PSA and the CTU are opposing a new round of staff cuts at WorkSafe, which they say ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald15 hours ago - Can the government change its mind on the ferries?

The decision to unilaterally repudiate the contract for new Cook Strait ferries is beginning to look like one of the stupidest decisions a New Zealand government ever made. While cancelling the ferries and their associated port infrastructure may have made this year's books look good, it means higher costs later, ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant15 hours ago

The decision to unilaterally repudiate the contract for new Cook Strait ferries is beginning to look like one of the stupidest decisions a New Zealand government ever made. While cancelling the ferries and their associated port infrastructure may have made this year's books look good, it means higher costs later, ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant15 hours ago - Notes from Afar: Will Luxon Attend Waitangi Day? And Opposition Calls Out Nicola Willis for “C...

Hi there! I’ve been overseas recently, looking after a situation with a family member. So apologies if there any less than focused posts! Vanuatu has just had a significant 7.3 earthquake. Two MFAT staff are unaccounted for with local fatalities.It’s always sad to hear of such things happening.I think of ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī18 hours ago

Hi there! I’ve been overseas recently, looking after a situation with a family member. So apologies if there any less than focused posts! Vanuatu has just had a significant 7.3 earthquake. Two MFAT staff are unaccounted for with local fatalities.It’s always sad to hear of such things happening.I think of ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī18 hours ago - Member’s morning

Today is a special member's morning, scheduled to make up for the government's theft of member's days throughout the year. First up was the first reading of Greg Fleming's Crimes (Increased Penalties for Slavery Offences) Amendment Bill, which was passed unanimously. Currently the House is debating the third reading of ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant19 hours ago

Today is a special member's morning, scheduled to make up for the government's theft of member's days throughout the year. First up was the first reading of Greg Fleming's Crimes (Increased Penalties for Slavery Offences) Amendment Bill, which was passed unanimously. Currently the House is debating the third reading of ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant19 hours ago - Going Backwards

We're going backwardsIgnoring the realitiesGoing backwardsAre you counting all the casualties?We are not there yetWhere we need to beWe are still in debtTo our insanitiesSongwriter: Martin Gore Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel21 hours ago

We're going backwardsIgnoring the realitiesGoing backwardsAre you counting all the casualties?We are not there yetWhere we need to beWe are still in debtTo our insanitiesSongwriter: Martin Gore Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel21 hours ago - Blaming Treasury & Labour, Willis looks for even more Austerity

Willis blamed Treasury for changing its productivity assumptions and Labour’s spending increases since Covid for the worsening Budget outlook. Photo: Getty ImagesMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Wednesday, December 18 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast above ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey21 hours ago

Willis blamed Treasury for changing its productivity assumptions and Labour’s spending increases since Covid for the worsening Budget outlook. Photo: Getty ImagesMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Wednesday, December 18 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast above ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey21 hours ago - December-24 AT Board Meeting

Today the Auckland Transport board meet for the last time this year. For those interested (and with time to spare), you can follow along via this MS Teams link from 10am. I’ve taken a quick look through the agenda items to see what I think the most interesting aspects are. ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L21 hours ago

Today the Auckland Transport board meet for the last time this year. For those interested (and with time to spare), you can follow along via this MS Teams link from 10am. I’ve taken a quick look through the agenda items to see what I think the most interesting aspects are. ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L21 hours ago - The Making of a Mental Health Rockstar

Hi,If you’re a New Zealander — you know who Mike King is. He is the face of New Zealand’s battle against mental health problems. He can be loud and brash. He raises, and is entrusted with, a lot of cash. Last year his “I Am Hope” charity reported a revenue ...David FarrierBy David Farrier22 hours ago

Hi,If you’re a New Zealander — you know who Mike King is. He is the face of New Zealand’s battle against mental health problems. He can be loud and brash. He raises, and is entrusted with, a lot of cash. Last year his “I Am Hope” charity reported a revenue ...David FarrierBy David Farrier22 hours ago - It could have been worse

Probably about the only consolation available from yesterday’s unveiling of the Half-Yearly Economic and Fiscal Update (HYEFU) is that it could have been worse. Though Finance Minister Nicola Willis has tightened the screws on future government spending, she has resisted the calls from hard-line academics, fiscal purists and fiscal hawks ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 day ago

Probably about the only consolation available from yesterday’s unveiling of the Half-Yearly Economic and Fiscal Update (HYEFU) is that it could have been worse. Though Finance Minister Nicola Willis has tightened the screws on future government spending, she has resisted the calls from hard-line academics, fiscal purists and fiscal hawks ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 day ago - The Deep Divisions of Local Government

The right have a stupid saying that is only occasionally true:When is democracy not democracy? When it hasn’t been voted on.While not true in regards to branches of government such as the judiciary, it’s a philosophy that probably should apply to recently-elected local government councillors. Nevertheless, this concept seemed to ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi1 day ago

The right have a stupid saying that is only occasionally true:When is democracy not democracy? When it hasn’t been voted on.While not true in regards to branches of government such as the judiciary, it’s a philosophy that probably should apply to recently-elected local government councillors. Nevertheless, this concept seemed to ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi1 day ago - Willis’ austerity strategy just isn’t working

Long story short: the Government’s austerity policy has driven the economy into a deeper and longer recession that means it will have to borrow $20 billion more over the next four years than it expected just six months ago. Treasury’s latest forecasts show the National-ACT-NZ First Government’s fiscal strategy of ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago

Long story short: the Government’s austerity policy has driven the economy into a deeper and longer recession that means it will have to borrow $20 billion more over the next four years than it expected just six months ago. Treasury’s latest forecasts show the National-ACT-NZ First Government’s fiscal strategy of ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 day ago - Sabin 33 #7 – Are solar projects hurting farmers and rural communities?

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia ...1 day ago

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia ...1 day ago - Join us for a pop-up Hoon at 5pm on HYEFU

The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

- ‘Ideas Worth Saving’: A Call for Papers

Some years ago, I found myself pondering the power of literature to endure. Or at least the power of some of it to endure, while the rest vanishes in mere decades: https://phuulishfellow.wordpress.com/2019/08/07/look-on-my-works-ye-mighty-and-despair-the-literary-future/. I have similarly had fun with the subject in some of my short stories, such as Another Alexandria ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2212 days ago

Some years ago, I found myself pondering the power of literature to endure. Or at least the power of some of it to endure, while the rest vanishes in mere decades: https://phuulishfellow.wordpress.com/2019/08/07/look-on-my-works-ye-mighty-and-despair-the-literary-future/. I have similarly had fun with the subject in some of my short stories, such as Another Alexandria ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2212 days ago - Corrections is torturing prisoners again

In 1998, in the wake of the Paremoremo Prison riot, the Department of Corrections established the "Behaviour Management Regime". Prisoners were locked in their cells for 22 or 23 hours a day, with no fresh air, no exercise, no social contact, no entertainment, and in some cases no clothes and ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago

In 1998, in the wake of the Paremoremo Prison riot, the Department of Corrections established the "Behaviour Management Regime". Prisoners were locked in their cells for 22 or 23 hours a day, with no fresh air, no exercise, no social contact, no entertainment, and in some cases no clothes and ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago - HYEFU and BPS data shows New Zealand is way off track

New data released by the Treasury shows that the economic policies of this Government have made things worse in the year since they took office, said NZCTU Economist Craig Renney. “Our fiscal indicators are all heading in the wrong direction – with higher levels of debt, a higher deficit, and ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago

New data released by the Treasury shows that the economic policies of this Government have made things worse in the year since they took office, said NZCTU Economist Craig Renney. “Our fiscal indicators are all heading in the wrong direction – with higher levels of debt, a higher deficit, and ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago - “Better economic management”

At the 2023 election, National basically ran on a platform of being better economic managers. So how'd that turn out for us? In just one year, they've fucked us for two full political terms: The government's books are set to remain deeply in the red for the near term ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago

At the 2023 election, National basically ran on a platform of being better economic managers. So how'd that turn out for us? In just one year, they've fucked us for two full political terms: The government's books are set to remain deeply in the red for the near term ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago - Shameless, clueless

AUSTERITYText within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedMy spreadsheet insists This pain leads straight to glory (File not found) Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago

AUSTERITYText within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedMy spreadsheet insists This pain leads straight to glory (File not found) Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack2 days ago - Minimum wage ‘increase’ is an effective cut

The NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi are saying that the Government should do the right thing and deliver minimum wage increases that don’t see workers fall further behind, in response to today’s announcement that the minimum wage will only be increased by 1.5%, well short of forecast inflation. “With inflation forecast ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago

The NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi are saying that the Government should do the right thing and deliver minimum wage increases that don’t see workers fall further behind, in response to today’s announcement that the minimum wage will only be increased by 1.5%, well short of forecast inflation. “With inflation forecast ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald2 days ago - Crazy ’bout a Sharp-dressed Man

Oh, I weptFor daysFilled my eyesWith silly tearsOh, yeaBut I don'tCare no moreI don't care ifMy eyes get soreSongwriters: Paul Rodgers / Paul Kossoff. Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago

Oh, I weptFor daysFilled my eyesWith silly tearsOh, yeaBut I don'tCare no moreI don't care ifMy eyes get soreSongwriters: Paul Rodgers / Paul Kossoff. Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel2 days ago - How much should you worry about a collapse of the Atlantic conveyor belt?

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Bob Henson In this aerial view, fingers of meltwater flow from the melting Isunnguata Sermia glacier descending from the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 11, 2024, near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. According to the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE), the ...2 days ago

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Bob Henson In this aerial view, fingers of meltwater flow from the melting Isunnguata Sermia glacier descending from the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 11, 2024, near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. According to the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE), the ...2 days ago - 8% ACT Party Creates One Ring To Rule Them All

In August, I wrote an article about David Seymour1 with a video of his testimony, to warn that there were grave dangers to his Ministry of Regulation:David Seymour's Ministry of Slush Hides Far Greater RisksWhy Seymour's exorbitant waste of taxpayers' money could be the least of concernThe money for Seymour ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī2 days ago

In August, I wrote an article about David Seymour1 with a video of his testimony, to warn that there were grave dangers to his Ministry of Regulation:David Seymour's Ministry of Slush Hides Far Greater RisksWhy Seymour's exorbitant waste of taxpayers' money could be the least of concernThe money for Seymour ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī2 days ago - When austerity worsens public debt & cuts GDP

Willis is expected to have to reveal the bitter fiscal fruits of her austerity strategy in the HYEFU later today. Photo: Lynn Grieveson/TheKakaMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Tuesday, December 17 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago

Willis is expected to have to reveal the bitter fiscal fruits of her austerity strategy in the HYEFU later today. Photo: Lynn Grieveson/TheKakaMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Tuesday, December 17 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey2 days ago - Govt to double number of toll roads

On Friday the government announced it would double the number of toll roads in New Zealand as well as make a few other changes to how toll roads are used in the country. The real issue though is not that tolling is being used but the suggestion it will make ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L2 days ago

On Friday the government announced it would double the number of toll roads in New Zealand as well as make a few other changes to how toll roads are used in the country. The real issue though is not that tolling is being used but the suggestion it will make ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L2 days ago - Luxon’s pre-emptive strike

The Prime Minister yesterday engaged in what looked like a pre-emptive strike designed to counter what is likely to be a series of depressing economic statistics expected before the end of the week. He opened his weekly post-Cabinet press conference with a recitation of the Government’s achievements. “It certainly has ...PolitikBy Richard Harman2 days ago

The Prime Minister yesterday engaged in what looked like a pre-emptive strike designed to counter what is likely to be a series of depressing economic statistics expected before the end of the week. He opened his weekly post-Cabinet press conference with a recitation of the Government’s achievements. “It certainly has ...PolitikBy Richard Harman2 days ago - Gordon Campbell On The Coalition’s Empty Gestures, And Abortion Refusal As The New Slavery

This whooping cough story from south Auckland is a good example of the coalition government’s approach to social need – spend money on urging people to get vaccinated but only after you’ve cut the funding to where they could get vaccinated. This has been the case all year with public ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor2 days ago

This whooping cough story from south Auckland is a good example of the coalition government’s approach to social need – spend money on urging people to get vaccinated but only after you’ve cut the funding to where they could get vaccinated. This has been the case all year with public ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor2 days ago - More public service contempt of parliament

Back in 2023 the New Zealand Council for Civil Liberties raised concerns about the inherent conflict of interest involved in public service agencies supporting parliamentary select committees. Our parliament is run on a shoestring, so depends on the public service for advice. But public service agencies work for Ministers, not ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago

Back in 2023 the New Zealand Council for Civil Liberties raised concerns about the inherent conflict of interest involved in public service agencies supporting parliamentary select committees. Our parliament is run on a shoestring, so depends on the public service for advice. But public service agencies work for Ministers, not ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant2 days ago - If There Is A God

And if there is a GodI know he likes to rockHe likes his loud guitarsHis spiders from MarsAnd if there is a GodI know he's watching meHe likes what he seesBut there's trouble on the breezeSongwriter: William Patrick Corgan Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago

And if there is a GodI know he likes to rockHe likes his loud guitarsHis spiders from MarsAnd if there is a GodI know he's watching meHe likes what he seesBut there's trouble on the breezeSongwriter: William Patrick Corgan Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago - A Lipstick Government

Here’s a quick round up of today’s political news:1. MORE FOOD BANKS, CHARITIES, DOMESTIC VIOLENCE SHELTERS AND YOUTH SOCIAL SERVICES SET TO CLOSE OR SCALE BACK AROUND THE COUNTRY AS GOVT CUTS FUNDINGSome of Auckland's largest foodbanks are warning they may need to close or significantly reduce food parcels after ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī3 days ago

Here’s a quick round up of today’s political news:1. MORE FOOD BANKS, CHARITIES, DOMESTIC VIOLENCE SHELTERS AND YOUTH SOCIAL SERVICES SET TO CLOSE OR SCALE BACK AROUND THE COUNTRY AS GOVT CUTS FUNDINGSome of Auckland's largest foodbanks are warning they may need to close or significantly reduce food parcels after ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī3 days ago - NZCTU open letter to Treasury on undue restrictions on restricted briefings

Iain Rennie, CNZMSecretary and Chief Executive to the TreasuryDear Secretary, Undue restrictions on restricted briefings This week, the Treasury barred representatives from four organisations, including the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions Te Kauae Kaimahi, from attending the restricted briefing for the Half-Year Economic and Fiscal Update. We had been ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald3 days ago

Iain Rennie, CNZMSecretary and Chief Executive to the TreasuryDear Secretary, Undue restrictions on restricted briefings This week, the Treasury barred representatives from four organisations, including the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions Te Kauae Kaimahi, from attending the restricted briefing for the Half-Year Economic and Fiscal Update. We had been ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald3 days ago - Why you won’t hear me advocate for electric cars

This is a guest post by Tim Adriaansen, a community, climate, and accessibility advocate. I won’t shut up about climate breakdown, and whenever possible I try to shift the focus of a climate conversation towards solutions. But you’ll almost never hear me give more than a passing nod to ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post3 days ago

This is a guest post by Tim Adriaansen, a community, climate, and accessibility advocate. I won’t shut up about climate breakdown, and whenever possible I try to shift the focus of a climate conversation towards solutions. But you’ll almost never hear me give more than a passing nod to ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post3 days ago - Coalition forced to back down on tolling Pahiatua track

A grassroots backlash has forced a backdown from Brown, but he is still eyeing up plenty of tolls for other new roads. And the pressure is on Willis to ramp up the Government’s austerity strategy. Photo: Getty ImagesMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago

A grassroots backlash has forced a backdown from Brown, but he is still eyeing up plenty of tolls for other new roads. And the pressure is on Willis to ramp up the Government’s austerity strategy. Photo: Getty ImagesMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago - Thank You

Hi all,I'm pretty overwhelmed by all your messages and emails today; thank you so very much.As much as my newsletter this morning was about money, and we all need to earn money, it was mostly about world domination if I'm honest. 😉I really hate what’s happening to our country, and ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago

Hi all,I'm pretty overwhelmed by all your messages and emails today; thank you so very much.As much as my newsletter this morning was about money, and we all need to earn money, it was mostly about world domination if I'm honest. 😉I really hate what’s happening to our country, and ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago - 2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #50

A listing of 23 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, December 8, 2024 thru Sat, December 14, 2024. Listing by Category Like last week's summary this one contains the list of articles twice: based on categories and based on ...3 days ago

A listing of 23 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, December 8, 2024 thru Sat, December 14, 2024. Listing by Category Like last week's summary this one contains the list of articles twice: based on categories and based on ...3 days ago - Making Gravy

I started writing this morning about Hobson’s Pledge, examining the claims they and their supporters make, basically ripping into them. But I kept getting notifications coming through, and not good ones.Each time I looked up, there was another un-subscription message, and I felt a bit sicker at the thought of ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago

I started writing this morning about Hobson’s Pledge, examining the claims they and their supporters make, basically ripping into them. But I kept getting notifications coming through, and not good ones.Each time I looked up, there was another un-subscription message, and I felt a bit sicker at the thought of ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago - Nothing here but the shadows

Once, long before there was Harry and Meghan and Dodi and all those episodes of The Crown, they came to spend some time with us, Charles and Diana. Was there anyone in the world more glamorous than the Princess of Wales?Dazzled as everyone was by their company, the leader of ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack4 days ago

Once, long before there was Harry and Meghan and Dodi and all those episodes of The Crown, they came to spend some time with us, Charles and Diana. Was there anyone in the world more glamorous than the Princess of Wales?Dazzled as everyone was by their company, the leader of ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack4 days ago - The United Right: the FSU’s Continued Efforts to Undermine Academia

The collective right have a problem.The entire foundation for their world view is antiscientific. Their preferred economic strategies have been disproven. Their whole neoliberal model faces accusations of corporate corruption and worsening inequality. Climate change not only definitely exists, its rapid progression demands an immediate and expensive response in order ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi4 days ago

- Showing the Americans how to do it

Just ten days ago, South Korea's president attempted a self-coup, declaring martial law and attempting to have opposition MPs murdered or arrested in an effort to seize unconstrained power. The attempt was rapidly defeated by the national assembly voting it down and the people flooding the streets to defend democracy. ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant4 days ago

Just ten days ago, South Korea's president attempted a self-coup, declaring martial law and attempting to have opposition MPs murdered or arrested in an effort to seize unconstrained power. The attempt was rapidly defeated by the national assembly voting it down and the people flooding the streets to defend democracy. ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant4 days ago - 2 Men, 1 Haircut

Hi,“What I love about New Zealanders is that sometimes you use these expressions that as Americans we have no idea what those things mean!"I am watching a 30-something year old American ramble on about how different New Zealanders are to Americans. It’s his podcast, and this man is doing a ...David FarrierBy David Farrier5 days ago

Hi,“What I love about New Zealanders is that sometimes you use these expressions that as Americans we have no idea what those things mean!"I am watching a 30-something year old American ramble on about how different New Zealanders are to Americans. It’s his podcast, and this man is doing a ...David FarrierBy David Farrier5 days ago - Chris Penk’s Hate Parade

What Chris Penk has granted holocaust-denier and equal-opportunity-bigot Candace Owens is not “freedom of speech”. It’s not even really freedom of movement, though that technically is the right she has been granted. What he has given her is permission to perform. Freedom of SpeechIn New Zealand, the right to freedom ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi5 days ago

What Chris Penk has granted holocaust-denier and equal-opportunity-bigot Candace Owens is not “freedom of speech”. It’s not even really freedom of movement, though that technically is the right she has been granted. What he has given her is permission to perform. Freedom of SpeechIn New Zealand, the right to freedom ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi5 days ago - Tell me a story

All those tears on your cheeksJust like deja vu flow nowWhen grandmother speaksSo tell me a story (I'll tell you a story)Spell it out, I can't hear (What do you want to hear?)Why you wear black in the morning?Why there's smoke in the air? Songwriter: Greg Johnson.Mōrena all ☀️Something a ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago

All those tears on your cheeksJust like deja vu flow nowWhen grandmother speaksSo tell me a story (I'll tell you a story)Spell it out, I can't hear (What do you want to hear?)Why you wear black in the morning?Why there's smoke in the air? Songwriter: Greg Johnson.Mōrena all ☀️Something a ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago - As Our Power Lessens: Accepted

2024 is now officially my best-ever year for short stories. My 1,850-word dark fantasy piece, As Our Power Lessens, has been accepted for the upcoming solstice edition of Eternal Haunted Summer (https://eternalhauntedsummer.com/), thereby making that six published short stories for the calendar year. As always, see the Bibliography page for ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2216 days ago

2024 is now officially my best-ever year for short stories. My 1,850-word dark fantasy piece, As Our Power Lessens, has been accepted for the upcoming solstice edition of Eternal Haunted Summer (https://eternalhauntedsummer.com/), thereby making that six published short stories for the calendar year. As always, see the Bibliography page for ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2216 days ago - Six years of work wasted – Holidays Act reform now years away

Brooke van Velden has wasted six years of work from businesses, unions, and government by binning planned Holidays Act reforms, said Acting CTU President Rachel Mackintosh in response to today’s announcement from Minister for Workplace Relations and Safety. “The Minister has cynically kicked the can on Holiday Act reform even ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald6 days ago

Brooke van Velden has wasted six years of work from businesses, unions, and government by binning planned Holidays Act reforms, said Acting CTU President Rachel Mackintosh in response to today’s announcement from Minister for Workplace Relations and Safety. “The Minister has cynically kicked the can on Holiday Act reform even ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald6 days ago - Come Undone?

Words, playing me deja vuLike a radio tune, I swear I've heard beforeChill, is it something real?Or the magic I'm feeding off your fingersWho do you need?Who do you love?When you come undoneSongwriters: John Taylor / Simon Le Bon / Nick Rhodes / Warren Cuccurullo.When this three-way coalition was being ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel6 days ago

Words, playing me deja vuLike a radio tune, I swear I've heard beforeChill, is it something real?Or the magic I'm feeding off your fingersWho do you need?Who do you love?When you come undoneSongwriters: John Taylor / Simon Le Bon / Nick Rhodes / Warren Cuccurullo.When this three-way coalition was being ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel6 days ago - ‘Tis The Season …

Last week, I was speaking to a doctor in a public health hospital.She was wearing a brown Christmas seasoned shirt littered with pics of candy canes, elves, Xmas trees and mini Santas.And it took me a few minutes into the conversation before the realisation slowly struck me: “It’s Christmas time..!”How ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui6 days ago

Last week, I was speaking to a doctor in a public health hospital.She was wearing a brown Christmas seasoned shirt littered with pics of candy canes, elves, Xmas trees and mini Santas.And it took me a few minutes into the conversation before the realisation slowly struck me: “It’s Christmas time..!”How ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui6 days ago - Friday 13 December

More public service job cuts are on the way, with hundreds more jobs set to be axed at Health NZ, and close to 50 jobs at Te Arawhiti. Winston Peters is saying Nicola Willis’ ferry proposal is now dead in the water and that he is going back to the ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald6 days ago

More public service job cuts are on the way, with hundreds more jobs set to be axed at Health NZ, and close to 50 jobs at Te Arawhiti. Winston Peters is saying Nicola Willis’ ferry proposal is now dead in the water and that he is going back to the ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald6 days ago - Govt cancels Tauranga housing expansion

Mōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Friday, December 12 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus above and the daily Pick ‘n’ Mix below are:The National-ACT-NZ First Government, which has a ‘Going for Housing Growth’ policy designed to massively ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago

Mōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Friday, December 12 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus above and the daily Pick ‘n’ Mix below are:The National-ACT-NZ First Government, which has a ‘Going for Housing Growth’ policy designed to massively ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago - Weekly Roundup 13-December-2024

It’s one of the final Fridays of the year and we are getting into the last couple of weeks before the summer shutdown. We hope everyone’s excited to have a break! Here’s some of the stories that have caught our attention this week. This post, like all our work, is ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland6 days ago

It’s one of the final Fridays of the year and we are getting into the last couple of weeks before the summer shutdown. We hope everyone’s excited to have a break! Here’s some of the stories that have caught our attention this week. This post, like all our work, is ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland6 days ago - The Hoon around the week to December 13

The podcast above of the weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers on Thursday night features co-hosts & talking about the week’s news with: on the Government’s inadequate final emissions reduction plan and pro-business climate appointments; on the lightening overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria and what might ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago

The podcast above of the weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers on Thursday night features co-hosts & talking about the week’s news with: on the Government’s inadequate final emissions reduction plan and pro-business climate appointments; on the lightening overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria and what might ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago - Our Education System Will Be the Battlegrounds for the New Culture War

Luxon is the best negotiator. He’s just negotiated us into a culture war and he doesn’t even know it. Neoliberalism is preventing our school system from serving the population. People — most people — cannot really select the schools their children go to unless they are wealthy enough to pay ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi6 days ago

Luxon is the best negotiator. He’s just negotiated us into a culture war and he doesn’t even know it. Neoliberalism is preventing our school system from serving the population. People — most people — cannot really select the schools their children go to unless they are wealthy enough to pay ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi6 days ago - The ferry saga; cracks in the coalition and closing Wellington’s container port

Yesterday, the coalition showed the first real public signs of cracks, as Ministers and the Prime Minister spent the day contradicting each other over the future of the inter-island ferries. The cracks between ACT and New Zealand First have always been there. But what made yesterday’s exchanges different was that ...PolitikBy Richard Harman6 days ago

Yesterday, the coalition showed the first real public signs of cracks, as Ministers and the Prime Minister spent the day contradicting each other over the future of the inter-island ferries. The cracks between ACT and New Zealand First have always been there. But what made yesterday’s exchanges different was that ...PolitikBy Richard Harman6 days ago - Chris Penk Personally Intervenes for Holocaust Denier

The general advertising strategy of far-right speakers for the last few years has been to announce they’re coming to New Zealand, wait for their visa to be denied or their venue to cancel on them, and then use that free promotion and outrage generation (sponsored by the Free Speech Union) ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi6 days ago

The general advertising strategy of far-right speakers for the last few years has been to announce they’re coming to New Zealand, wait for their visa to be denied or their venue to cancel on them, and then use that free promotion and outrage generation (sponsored by the Free Speech Union) ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi6 days ago - Wulf vs Beowulf: A Review of The War of the Rohirrim (2024)

Oh good. Back to the Tolkien adaptations. Not just any Tolkien adaptation either. The story of Helm Hammerhand, as done in anime style – something a bit different. It’s actually the first animated Tolkien adaptation since Rankin-Bass’ Return of the King in 1980, as well as the first Tolkien adaptation ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2216 days ago

Oh good. Back to the Tolkien adaptations. Not just any Tolkien adaptation either. The story of Helm Hammerhand, as done in anime style – something a bit different. It’s actually the first animated Tolkien adaptation since Rankin-Bass’ Return of the King in 1980, as well as the first Tolkien adaptation ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2216 days ago - Georgescu and the Arrogance of the West

I enjoy reading the views of pundits and people. I like knowing what they think, and why they think it. But sometimes I look at what commentators are saying and where conversations are leading and I despair. How often do we here on the left do the right’s job for ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi6 days ago

I enjoy reading the views of pundits and people. I like knowing what they think, and why they think it. But sometimes I look at what commentators are saying and where conversations are leading and I despair. How often do we here on the left do the right’s job for ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi6 days ago - Gordon Campbell On The Latest Round Of Ferry Follies

The scorned iRex option would have entered service in 2026. Thanks to Finance Minister Nicola Willis, there will now be a three year delay until 2029 at the earliest. Instead of fit-for-purpose iRex ferries, Willis is likely by then to have saddled us with smaller, less capable, more weather vulnerable ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor6 days ago

The scorned iRex option would have entered service in 2026. Thanks to Finance Minister Nicola Willis, there will now be a three year delay until 2029 at the earliest. Instead of fit-for-purpose iRex ferries, Willis is likely by then to have saddled us with smaller, less capable, more weather vulnerable ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor6 days ago - Rotten to the core

Just a few months ago, Deputy Commissioner Jevon McSkimming was one of the final two candidates for the position of police commissioner. Now, he's on leave and facing multiple investigations for unspecified wrongdoing: The second-most powerful police officer in the country is on leave pending separate investigations, the Herald ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago

Just a few months ago, Deputy Commissioner Jevon McSkimming was one of the final two candidates for the position of police commissioner. Now, he's on leave and facing multiple investigations for unspecified wrongdoing: The second-most powerful police officer in the country is on leave pending separate investigations, the Herald ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago - Skeptical Science New Research for Week #50 2024

Open access notables: Regional Impacts Poorly Constrained by Climate Sensitivity, Swaminathan et al., Earth's Future: Climate risk assessments must account for a wide range of possible futures, so scientists often use simulations made by numerous global climate models to explore potential changes in regional climates and their impacts. Some of ...6 days ago

Open access notables: Regional Impacts Poorly Constrained by Climate Sensitivity, Swaminathan et al., Earth's Future: Climate risk assessments must account for a wide range of possible futures, so scientists often use simulations made by numerous global climate models to explore potential changes in regional climates and their impacts. Some of ...6 days ago - About Syria.

I have been thinking about Syria and coverage of the fall of the Assad regime, and to be honest I believe that there is something missing from the picture being painted, at least in NZ. Although I am no expert … Continue reading → ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo7 days ago

I have been thinking about Syria and coverage of the fall of the Assad regime, and to be honest I believe that there is something missing from the picture being painted, at least in NZ. Although I am no expert … Continue reading → ...KiwipoliticoBy Pablo7 days ago - The Two Hundred Million Dollar question

Here we see Napoleon delivering glory in Russia.Here we see Elizabeth Holmes delivering a blood test for anything. Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack7 days ago

Here we see Napoleon delivering glory in Russia.Here we see Elizabeth Holmes delivering a blood test for anything. Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack7 days ago - Luxon & Willis Double Down on Ferries Debacle

The day before today, Nicola Willis told the House that they would have to wait until the ferries announcement for the details about ferries cost etc. It was the same promise Luxon has been making in Parliament over the last weeks and months: the details are coming, the details are ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui7 days ago

The day before today, Nicola Willis told the House that they would have to wait until the ferries announcement for the details about ferries cost etc. It was the same promise Luxon has been making in Parliament over the last weeks and months: the details are coming, the details are ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tui7 days ago - Luigi Mangione and Jury Nullification

Luigi Mangione, the shooter of the Ultimate Healthcare CEO, has been caught by the cops after a tip-off from a McDonalds worker. (A timely reminder, perhaps, that there is an official boycott against McDonalds for their profiting from and support of Israel’s occupation in Palestine, and it has been having ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi7 days ago

Luigi Mangione, the shooter of the Ultimate Healthcare CEO, has been caught by the cops after a tip-off from a McDonalds worker. (A timely reminder, perhaps, that there is an official boycott against McDonalds for their profiting from and support of Israel’s occupation in Palestine, and it has been having ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi7 days ago - Thursday 12 December

There has been widespread condemnation of the Government’s mishandling of the Cook Strait ferry replacements, including from unions, industry, and political parties. It has also led to public division among the coalition, with Winston Peters and David Seymour at odds regarding cost and privatisation. In other political news, Labour says ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald7 days ago

There has been widespread condemnation of the Government’s mishandling of the Cook Strait ferry replacements, including from unions, industry, and political parties. It has also led to public division among the coalition, with Winston Peters and David Seymour at odds regarding cost and privatisation. In other political news, Labour says ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald7 days ago - Foreshadowing HYEFU 2024

By way of prologue, the closest parallel to the current economic situation may be when Ruth Richardson became Minister of Finance in late 1990. The economy had been contracting, although there were signs of a fragile recovery. She was an Austerian and cut public spending savagely. The economy plunged a ...PunditBy Brian Easton7 days ago

By way of prologue, the closest parallel to the current economic situation may be when Ruth Richardson became Minister of Finance in late 1990. The economy had been contracting, although there were signs of a fragile recovery. She was an Austerian and cut public spending savagely. The economy plunged a ...PunditBy Brian Easton7 days ago - How unusual is current post-El Niño warmth?

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink As I noted a few months back, despite the end of El Niño conditions in May, global temperatures have remained worryingly elevated. This raises the question of whether this reflects unusual El Niño behavior, or a more persistent change in the underlying climate forcings ...7 days ago

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink As I noted a few months back, despite the end of El Niño conditions in May, global temperatures have remained worryingly elevated. This raises the question of whether this reflects unusual El Niño behavior, or a more persistent change in the underlying climate forcings ...7 days ago - Nicky No Boats

I remember you by, thunderclap in the skyLightning flash, tempers flare'Round the horn if you dareI just spent six months in a leaky boatLucky just to keep afloatSongwriters: Brian Timothy FinnToday, a tale of such ineptitude, unwarranted confidence and underplanning that you will scarcely believe it. I can hear you ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel7 days ago

I remember you by, thunderclap in the skyLightning flash, tempers flare'Round the horn if you dareI just spent six months in a leaky boatLucky just to keep afloatSongwriters: Brian Timothy FinnToday, a tale of such ineptitude, unwarranted confidence and underplanning that you will scarcely believe it. I can hear you ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel7 days ago - Ferries delayed again, then handed to Peters, who hits out at Seymour

Willis wouldn’t give a cost estimate or confirm new ferries would be ‘rail enabled’ rather than ‘rail-compatible’, but Seymour has let slip the ferries and ‘landside’ development would cost around $1.5 billion. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey7 days ago

Willis wouldn’t give a cost estimate or confirm new ferries would be ‘rail enabled’ rather than ‘rail-compatible’, but Seymour has let slip the ferries and ‘landside’ development would cost around $1.5 billion. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey7 days ago - When Should You Consider Retreat? – The Sooner the Better

This is a guest post by Waitematā local board member Dr Alex Bonham, about the Auckland Council’s Shoreline Adaption Plans. Currently consultation is open for the Auckland Central & Ōrākei to Karaka Bay SAPs until December 18th. If the sea bowls through your front door, through the house and ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post7 days ago

This is a guest post by Waitematā local board member Dr Alex Bonham, about the Auckland Council’s Shoreline Adaption Plans. Currently consultation is open for the Auckland Central & Ōrākei to Karaka Bay SAPs until December 18th. If the sea bowls through your front door, through the house and ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post7 days ago - Shameless advertising: Two days only — 50% off subscriptions, forever

But wait!! If you would like to pay me LESS, on Friday the discount will be bigger. Subscription benefits include my endless gratitude, warm fuzzy feelings, bragging rights, and a slight spring in your step. ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi7 days ago

But wait!! If you would like to pay me LESS, on Friday the discount will be bigger. Subscription benefits include my endless gratitude, warm fuzzy feelings, bragging rights, and a slight spring in your step. ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi7 days ago

Related Posts

- Release: Hikes for company directors but not ordinary Kiwis

14 hours ago

- ECE no place to cut corners

The Ministry of Regulation’s report into Early Childhood Education (ECE) in Aotearoa raises serious concerns about the possibility of lowering qualification requirements, undermining quality and risking worse outcomes for tamariki, whānau, and kaiako. ...16 hours ago

The Ministry of Regulation’s report into Early Childhood Education (ECE) in Aotearoa raises serious concerns about the possibility of lowering qualification requirements, undermining quality and risking worse outcomes for tamariki, whānau, and kaiako. ...16 hours ago - Release: Strengthening Justice Services for New Zealanders

A Bill to modernise the role of Justices of the Peace (JP), ensuring they remain active in their communities and connected with other JPs, has been put into the ballot. ...17 hours ago

A Bill to modernise the role of Justices of the Peace (JP), ensuring they remain active in their communities and connected with other JPs, has been put into the ballot. ...17 hours ago - Release: Labour will continue fight against destructive projects

Labour will continue to fight unsustainable and destructive projects that are able to leap-frog environment protection under National’s Fast-track Approvals Bill. ...1 day ago

Labour will continue to fight unsustainable and destructive projects that are able to leap-frog environment protection under National’s Fast-track Approvals Bill. ...1 day ago - Green Government will revoke dodgy fast-track projects

The Green Party has warned that a Green Government will revoke the consents of companies who override environmental protections as part of Fast-Track legislation being passed today. ...1 day ago

The Green Party has warned that a Green Government will revoke the consents of companies who override environmental protections as part of Fast-Track legislation being passed today. ...1 day ago - Government for the wealthy keeps pushing austerity

The Green Party says the Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update shows how the Government is failing to address the massive social and infrastructure deficits our country faces. ...2 days ago

The Green Party says the Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update shows how the Government is failing to address the massive social and infrastructure deficits our country faces. ...2 days ago - Release: Visa changes let migrant workers be paid less

The Government’s latest move to reduce the earnings of migrant workers will not only hurt migrants but it will drive down the wages of Kiwi workers. ...2 days ago

The Government’s latest move to reduce the earnings of migrant workers will not only hurt migrants but it will drive down the wages of Kiwi workers. ...2 days ago - Release: Nightmare before Christmas for Nicola Willis

With more debt and a larger deficit, Nicola Willis’ reputation is in tatters after her failure to return the Government’s books to surplus. ...2 days ago

With more debt and a larger deficit, Nicola Willis’ reputation is in tatters after her failure to return the Government’s books to surplus. ...2 days ago - Warning to Fast-Track Applicants – ‘Exploit the Whenua, Face the Consequences’

Te Pāti Māori has this morning issued a stern warning to Fast-Track applicants with interests in mining, pledging to hold them accountable through retrospective liability and to immediately revoke Fast-Track consents under a future Te Pāti Māori government. This warning comes ahead of today’s third reading of the Fast-Track Approvals ...2 days ago

Te Pāti Māori has this morning issued a stern warning to Fast-Track applicants with interests in mining, pledging to hold them accountable through retrospective liability and to immediately revoke Fast-Track consents under a future Te Pāti Māori government. This warning comes ahead of today’s third reading of the Fast-Track Approvals ...2 days ago - Release: Govt cuts wages for lowest paid NZers… again

For the second year running, the government has effectively cut wages for the lowest paid workers in New Zealand. ...2 days ago

For the second year running, the government has effectively cut wages for the lowest paid workers in New Zealand. ...2 days ago - Govt’s miserly 1.5% minimum wage will take workers backwards

The Government’s announcement today of a 1.5 per cent increase to minimum wage is another blow for workers, with inflation projected to exceed the increase, meaning it’s a real terms pay reduction for many. ...2 days ago

The Government’s announcement today of a 1.5 per cent increase to minimum wage is another blow for workers, with inflation projected to exceed the increase, meaning it’s a real terms pay reduction for many. ...2 days ago - Release: Govt shirking responsibility for rate hikes

All the Government has achieved from its announcement today is to continue to push responsibility back on councils for its own lack of action to help bring down skyrocketing rates. ...2 days ago

All the Government has achieved from its announcement today is to continue to push responsibility back on councils for its own lack of action to help bring down skyrocketing rates. ...2 days ago - Luxon’s ‘localism’ strikes again

The Government has used its final post-Cabinet press conference of the year to punch down on local government without offering any credible solutions to the issues our councils are facing. ...2 days ago

The Government has used its final post-Cabinet press conference of the year to punch down on local government without offering any credible solutions to the issues our councils are facing. ...2 days ago - Release: Govt breaks promise on EV chargers

The Government has failed to keep its promise to ‘super charge’ the EV network, delivering just 292 chargers - less than half of the 670 chargers needed to meet its target. ...3 days ago

The Government has failed to keep its promise to ‘super charge’ the EV network, delivering just 292 chargers - less than half of the 670 chargers needed to meet its target. ...3 days ago - Greens call for end to subsidies for Methanex

The Green Party is calling for the Government to stop subsidising the largest user of the country’s gas supplies, Methanex, following a report highlighting the multi-national’s disproportionate influence on energy prices in Aotearoa. ...3 days ago

The Green Party is calling for the Government to stop subsidising the largest user of the country’s gas supplies, Methanex, following a report highlighting the multi-national’s disproportionate influence on energy prices in Aotearoa. ...3 days ago - Govt child poverty targets allow for increase in poverty

The Green Party is appalled with the Government’s new child poverty targets that are based on a new ‘persistent poverty’ measure that could be met even with an increase in child poverty. ...6 days ago

The Green Party is appalled with the Government’s new child poverty targets that are based on a new ‘persistent poverty’ measure that could be met even with an increase in child poverty. ...6 days ago - Release: Four weeks annual leave under threat

The Government’s attack on workers continues with news it is scrapping work on the Holidays Act. ...6 days ago

The Government’s attack on workers continues with news it is scrapping work on the Holidays Act. ...6 days ago - Govt’s emissions plan for measly 1% reduction

New independent analysis has revealed that the Government’s Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) will reduce emissions by a measly 1 per cent by 2030, failing to set us up for the future and meeting upcoming targets. ...6 days ago

New independent analysis has revealed that the Government’s Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) will reduce emissions by a measly 1 per cent by 2030, failing to set us up for the future and meeting upcoming targets. ...6 days ago - Greens stand in solidarity with Whakaata Māori on sad day

The loss of 27 kaimahi at Whakaata Māori and the end of its daily news bulletin is a sad day for Māori media and another step backwards for Te Tiriti o Waitangi justice. ...6 days ago

The loss of 27 kaimahi at Whakaata Māori and the end of its daily news bulletin is a sad day for Māori media and another step backwards for Te Tiriti o Waitangi justice. ...6 days ago - Sanctions regime to create more hardship for families

Yesterday the Government passed cruel legislation through first reading to establish a new beneficiary sanction regime that will ultimately mean more households cannot afford the basic essentials. ...6 days ago

Yesterday the Government passed cruel legislation through first reading to establish a new beneficiary sanction regime that will ultimately mean more households cannot afford the basic essentials. ...6 days ago - Govt gifts renters housing anxiety for Christmas

Today's passing of the Government's Residential Tenancies Amendment Bill–which allows landlords to end tenancies with no reason–ignores the voice of the people and leaves renters in limbo ahead of the festive season. ...6 days ago

Today's passing of the Government's Residential Tenancies Amendment Bill–which allows landlords to end tenancies with no reason–ignores the voice of the people and leaves renters in limbo ahead of the festive season. ...6 days ago - Release: National Party urged to support modern slavery legislation

Labour is urging the Prime Minister to walk the talk and support legislation combating modern slavery. ...7 days ago

Labour is urging the Prime Minister to walk the talk and support legislation combating modern slavery. ...7 days ago - Release: Labour has lost confidence in the Speaker

The Speaker of the New Zealand Parliament made an unprecedented decision on the government amendment to the Fast Track Approvals Bill last night. ...7 days ago

The Speaker of the New Zealand Parliament made an unprecedented decision on the government amendment to the Fast Track Approvals Bill last night. ...7 days ago - One year on, still no progress on new ferries

Today’s announcement from the Government on its plan for new ferries throws more uncertainty on the future of the country’s rail network. ...1 week ago

Today’s announcement from the Government on its plan for new ferries throws more uncertainty on the future of the country’s rail network. ...1 week ago - Release: Nicola Willis’ smaller ferries will cost more

After wasting a year, Nicola Willis has delivered a worse deal for the Cook Strait ferries that will end up being more expensive and take longer to arrive. ...1 week ago

After wasting a year, Nicola Willis has delivered a worse deal for the Cook Strait ferries that will end up being more expensive and take longer to arrive. ...1 week ago - Bill to sanction unlawful occupation of Palestine

Green Party co-leader Chlöe Swarbrick has today launched a Member’s Bill to sanction Israel for its unlawful presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, as the All Out For Gaza rally reaches Parliament. ...1 week ago

Green Party co-leader Chlöe Swarbrick has today launched a Member’s Bill to sanction Israel for its unlawful presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, as the All Out For Gaza rally reaches Parliament. ...1 week ago - Release: Labour fully supports greyhound racing ban

1 week ago

- Greyhound racing industry ban marks new era for animal welfare

After years of advocacy, the Green Party is very happy to hear the Government has listened to our collective voices and announced the closure of the greyhound racing industry, by 1 August 2026. ...1 week ago

After years of advocacy, the Green Party is very happy to hear the Government has listened to our collective voices and announced the closure of the greyhound racing industry, by 1 August 2026. ...1 week ago - Rangatahi voices must be centred in Government’s Relationship and Sexuality Education refresh

In response to a new report from ERO, the Government has acknowledged the urgent need for consistency across the curriculum for Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE) in schools. ...1 week ago

In response to a new report from ERO, the Government has acknowledged the urgent need for consistency across the curriculum for Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE) in schools. ...1 week ago - Govt introduces archaic anti-worker legislation

The Green Party is appalled at the Government introducing legislation that will make it easier to penalise workers fighting for better pay and conditions. ...1 week ago

The Green Party is appalled at the Government introducing legislation that will make it easier to penalise workers fighting for better pay and conditions. ...1 week ago - Winston Peters – Kinleith Mill Speech

Thank you for the invitation to speak with you tonight on behalf of the political party I belong to - which is New Zealand First. As we have heard before this evening the Kinleith Mill is proposing to reduce operations by focusing on pulp and discontinuing “lossmaking paper production”. They say that they are currently consulting on the plan to permanently shut ...1 week ago

Thank you for the invitation to speak with you tonight on behalf of the political party I belong to - which is New Zealand First. As we have heard before this evening the Kinleith Mill is proposing to reduce operations by focusing on pulp and discontinuing “lossmaking paper production”. They say that they are currently consulting on the plan to permanently shut ...1 week ago - Swarbrick calls on Auckland Mayor to end delay of revival of St James Theatre

Auckland Central MP, Chlöe Swarbrick, has written to Mayor Wayne Brown requesting he stop the unnecessary delays on St James Theatre’s restoration. ...2 weeks ago

Auckland Central MP, Chlöe Swarbrick, has written to Mayor Wayne Brown requesting he stop the unnecessary delays on St James Theatre’s restoration. ...2 weeks ago - He Ara Anamata: Greens launch Emissions Reduction Plan

Today, the Green Party of Aotearoa proudly unveils its new Emissions Reduction Plan–He Ara Anamata–a blueprint reimagining our collective future. ...2 weeks ago

Today, the Green Party of Aotearoa proudly unveils its new Emissions Reduction Plan–He Ara Anamata–a blueprint reimagining our collective future. ...2 weeks ago - Fossil fuel lobbyist appointment to EECA board called out

The Green Party condemns the Government’s appointment of a fossil fuel lobbyist to the Energy Efficiency & Conservation Authority Board. ...2 weeks ago

The Green Party condemns the Government’s appointment of a fossil fuel lobbyist to the Energy Efficiency & Conservation Authority Board. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Boot camps must be shut down today

The Prime Minister has committed to shut down his government’s boot camps if there is evidence of harm to children – so he must do that today. ...2 weeks ago

The Prime Minister has committed to shut down his government’s boot camps if there is evidence of harm to children – so he must do that today. ...2 weeks ago - Greens echo OECD call for electricity market reform

The Green Party has welcomed the OECD urging the Government to re-examine separating ‘gentailers’ to make a fairer electricity market for New Zealanders. ...2 weeks ago

The Green Party has welcomed the OECD urging the Government to re-examine separating ‘gentailers’ to make a fairer electricity market for New Zealanders. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Govt breaks Auckland housing promise

2 weeks ago

- Government smokescreen to downgrade climate ambition

Today the ACT-National Coalition Agreement pet project’s findings on “no additional warming” were released. ...2 weeks ago

Today the ACT-National Coalition Agreement pet project’s findings on “no additional warming” were released. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Health NZ admits errors led to claimed deficit

2 weeks ago

- Release: More cuts to research, science and innovation sector

The Government’s latest round of cuts to research and innovation targets the long-established and successful Marsden Fund. ...2 weeks ago

The Government’s latest round of cuts to research and innovation targets the long-established and successful Marsden Fund. ...2 weeks ago

Related Posts

- Levelling the playing field for media advertising

Legislation that will repeal all advertising restrictions for broadcasters on Sundays and public holidays has passed through first reading in Parliament today, Media Minister Paul Goldsmith says. “As a growing share of audiences get their news and entertainment from streaming services, these restrictions have become increasingly redundant. New Zealand on ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz13 hours ago

Legislation that will repeal all advertising restrictions for broadcasters on Sundays and public holidays has passed through first reading in Parliament today, Media Minister Paul Goldsmith says. “As a growing share of audiences get their news and entertainment from streaming services, these restrictions have become increasingly redundant. New Zealand on ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz13 hours ago - Inspector-General of Defence appointed

Today the House agreed to Brendan Horsley being appointed Inspector-General of Defence, Justice Minister Paul Goldsmith says. “Mr Horsley’s experience will be invaluable in overseeing the establishment of the new office and its support networks. “He is currently Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security, having held that role since June 2020. ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz13 hours ago

Today the House agreed to Brendan Horsley being appointed Inspector-General of Defence, Justice Minister Paul Goldsmith says. “Mr Horsley’s experience will be invaluable in overseeing the establishment of the new office and its support networks. “He is currently Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security, having held that role since June 2020. ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz13 hours ago - Fire and Emergency New Zealand final levy rates confirmed

Minister of Internal Affairs Brooke van Velden says the Government has agreed to the final regulations for the levy on insurance contracts that will fund Fire and Emergency New Zealand from July 2026. “Earlier this year the Government agreed to a 2.2 percent increase to the rate of levy. Fire ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz14 hours ago

Minister of Internal Affairs Brooke van Velden says the Government has agreed to the final regulations for the levy on insurance contracts that will fund Fire and Emergency New Zealand from July 2026. “Earlier this year the Government agreed to a 2.2 percent increase to the rate of levy. Fire ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz14 hours ago - More AML relief on the way for Kiwi businesses

The Government is delivering regulatory relief for New Zealand businesses through changes to the Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Act. “The Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Amendment Bill, which was introduced today, is the second Bill – the other being the Statutes Amendment Bill - that ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz14 hours ago

The Government is delivering regulatory relief for New Zealand businesses through changes to the Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Act. “The Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Amendment Bill, which was introduced today, is the second Bill – the other being the Statutes Amendment Bill - that ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz14 hours ago - Hawke’s Bay Expressway moving at pace