The Tinkers

The Tinkers

Written By:

RedLogix - Date published:

9:45 am, January 3rd, 2021 - Comments Off on The Tinkers

Categories: uncategorized -

Tags:

My all time favourite sci-fi author Vernor Vinge depicted in his Peace War Trilogy a counter culture that had adapted to unique set of circumstances to produce a high tech/low energy society. The back story involves the discovery of a new weapon. Vinge being a computer scientist himself (he taught in the field at San Diego State U) writes up a tantalisingly plausible methodology, invoking both advanced mathematics, next generation hardware platforms and lots of energy to produce a perfectly spherical, impenetrable, mirror surfaced containment volume, colloquially called a ‘bobble’. The diameter and location of a bobble were input parameters to the process, and could be projected over some distance from the generator, all depending on the energy and computational power available.

It appeared that once created anything trapped inside was sealed off from the rest of the universe for ever, and impervious to all attempts at undoing them, bobbles became the ultimate weapon. A totalitarian ‘Peace Authority’ gained early control of all bobble generators and the large power plants required to run them, asserting a global monopoly on political and economic power. Vinge, as with many good scifi authors has a definite libertarian streak in him, and his plot sets about the undoing of these villans.

The key element of this plot is that, in order to prevent anyone else obtaining bobble technology, the Peace Authority has to impose draconian limits on the energy sources and technologies available to the wider population. In the wake of a series of disasters population plummets, the survivors are much reduced although this is not an grimly dystopian world. Life reverts back to pre-industrial agrarian technologies. Most people become farmers again and are able to leverage sufficient tools and machinery to be reasonably productive. Horse and oxen power transport, village markets thrive, and those features of modernity that can be preserved (such as basic health, education and police) are adapted to the new circumstances.

Importantly an underground maker culture appears, calling themselves the Tinkers. Driven by the strict energy constraints they have to operate under, they find clandestine ways to rebuild some of the old industrial era technologies but operating with far lower energy. (For instance they had developed a very low power, highly encoded telecommunication network, relatively undetectable to the PA. This being a magical plot device in the 80’s yet just 30 years later became real; it’s called your cellphone.)

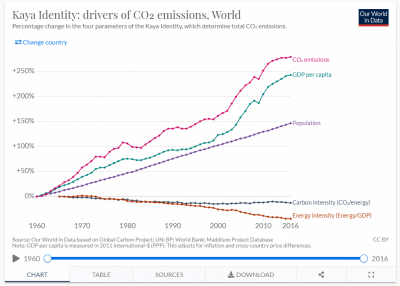

And while it wasn’t Vinge’s intention, this plot invokes very similar constraints advocated in the real world by some climate change activists, making story an interesting thought experiment. This ‘high tech/low energy’ path is an idea worth exploring, can our own society evolve a similar response to a similar pressure? This links to the third term in the Kaya Identity explored in this post that relates to energy intensity E/G. Can this term be driven low enough to reduce total carbon to the necessary level?

On the immediate face of it, the answer is no. Since roughly the 1960’s the developed world has gradually driven energy intensity down. Fortunately Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie have done the data work for us; if you are going to follow just one link please check this one, it’s central to this post. Conclusively it’s shows that while technology has been improving energy efficiencies for many decades, population growth and prosperity have nonetheless dominated the outcome.

The E/G term in the Kaya Identity is fundamentally constrained by underlying Laws of Thermodynamics, which tell us that all energy conversion processes (which is what all technology is at root) have an upper ideal limit. We can approach that ideal limit (and in some cases such as massive ship diesel engines we get amazingly close to them), but we can never exceed them. We can never drive this term to zero. Vinge’s fictional world appeals to our innate sense that efficiency is highly desirable, but the boundary between reality and fantasy is drawn by hard physical laws we can never step over.

Related Posts

Comments are closed.

Recent Posts

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by Mike Smith

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mike Smith

-

by Incognito

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by Guest post

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by Mike Smith

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by mickysavage

-

by Mountain Tui

-

by advantage

-

by lprent

-

by mickysavage

-

by weka

-

by Mountain Tui

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #52 2024

Open access notables Trends in Oceanic Precipitation Characteristics Inferred From Shipboard Present-Weather Reports, 1950–2019, Tran & Petty, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres: Although ship reports are susceptible to subjective interpretation, the inferred distributions of these phenomena are consistent with observations from other platforms such as satellites and coastal surface stations. ...2 hours ago

Open access notables Trends in Oceanic Precipitation Characteristics Inferred From Shipboard Present-Weather Reports, 1950–2019, Tran & Petty, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres: Although ship reports are susceptible to subjective interpretation, the inferred distributions of these phenomena are consistent with observations from other platforms such as satellites and coastal surface stations. ...2 hours ago - Todd Stephenson and Stephen Rainbow: David Farrar’s Ideological Plant In The Human Rights Commissi...

In 2018, David Farrar wrote a series of suggestions on Kiwiblog as to how the far right might best promote freedom of speech as a method of limiting other civil rights (in this particular case, academic freedom, a campaign that has just paid off this this month as David Seymour ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi11 hours ago

In 2018, David Farrar wrote a series of suggestions on Kiwiblog as to how the far right might best promote freedom of speech as a method of limiting other civil rights (in this particular case, academic freedom, a campaign that has just paid off this this month as David Seymour ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi11 hours ago - A Magical Time of Year

Because you're magicYou're magic people to meSong: Dave Para/Molly Para.Morena all, I hope you had a good day yesterday, however you spent it. Today, a few words about our celebration and a look at the various messages from our politicians.A Rockel XmasChristmas morning was spent with the five of us ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel11 hours ago

Because you're magicYou're magic people to meSong: Dave Para/Molly Para.Morena all, I hope you had a good day yesterday, however you spent it. Today, a few words about our celebration and a look at the various messages from our politicians.A Rockel XmasChristmas morning was spent with the five of us ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel11 hours ago - Climate Adam: 2024 Through the Eyes of a Climate Scientist

This video includes personal musings and conclusions of the creator climate scientist Dr. Adam Levy. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any). 2024 has been a series of bad news for climate change. From scorching global temperatures leading to devastating ...1 day ago

This video includes personal musings and conclusions of the creator climate scientist Dr. Adam Levy. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any). 2024 has been a series of bad news for climate change. From scorching global temperatures leading to devastating ...1 day ago - Merry Christmas To All Bowalley Road Readers.

Ríu Ríu ChíuRíu Ríu Chíu is a Spanish Christmas song from the 16th Century. The traditional carol would likely have passed unnoticed by the English-speaking world had the made-for-television American band The Monkees not performed the song as part of their special Christmas show back in 1967. The show's ...2 days ago

Ríu Ríu ChíuRíu Ríu Chíu is a Spanish Christmas song from the 16th Century. The traditional carol would likely have passed unnoticed by the English-speaking world had the made-for-television American band The Monkees not performed the song as part of their special Christmas show back in 1967. The show's ...2 days ago - Merry Christmas: 2024

Dunedin’s summer thus far has been warm and humid… and it looks like we’re in for a grey Christmas. But it is now officially Christmas Day in this time zone, so never mind. This year, I’ve stumbled across an Old English version of God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen: It has a population of just under 3.5 million inhabitants, produces nearly 550,000 tons of beef per year, and boasts a glorious soccer reputation with two World ...3 days ago

Dunedin’s summer thus far has been warm and humid… and it looks like we’re in for a grey Christmas. But it is now officially Christmas Day in this time zone, so never mind. This year, I’ve stumbled across an Old English version of God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen: It has a population of just under 3.5 million inhabitants, produces nearly 550,000 tons of beef per year, and boasts a glorious soccer reputation with two World ...3 days ago - Meri Kirihimete 2024

Morena all,In my paywalled newsletter yesterday, I signed off for Christmas and wished readers well, but I thought I’d send everyone a quick note this morning.This hasn’t been a good year for our small country. The divisions caused by the Treaty Principles Bill, the cuts to our public sector, increased ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago

Morena all,In my paywalled newsletter yesterday, I signed off for Christmas and wished readers well, but I thought I’d send everyone a quick note this morning.This hasn’t been a good year for our small country. The divisions caused by the Treaty Principles Bill, the cuts to our public sector, increased ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel3 days ago - Bernard’s Pick ‘n’ Mix for Tues, Dec 24

This morning’s six standouts for me at 6.30 am include:Kāinga Ora is quietly planning to sell over $1 billion worth of state-owned land under 300 state homes in Auckland’s wealthiest suburbs, including around Bastion Point, to give the Government more fiscal room to pay for tax cuts and reduce borrowing.A ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago

This morning’s six standouts for me at 6.30 am include:Kāinga Ora is quietly planning to sell over $1 billion worth of state-owned land under 300 state homes in Auckland’s wealthiest suburbs, including around Bastion Point, to give the Government more fiscal room to pay for tax cuts and reduce borrowing.A ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey3 days ago - A Birthday Wish!

Hi,It’s my birthday on Christmas Day, and I have a favour to ask.A birthday wish.I would love you to share one Webworm story you’ve liked this year.The simple fact is: apart from paying for a Webworm membership (thank you!), sharing and telling others about this place is the most important ...David FarrierBy David Farrier3 days ago

Hi,It’s my birthday on Christmas Day, and I have a favour to ask.A birthday wish.I would love you to share one Webworm story you’ve liked this year.The simple fact is: apart from paying for a Webworm membership (thank you!), sharing and telling others about this place is the most important ...David FarrierBy David Farrier3 days ago - Love, happiness, blur

The last few days have been a bit too much of a whirl for me to manage a fresh edition each day. It's been that kind of year. Hope you don't mind.I’ve been coming around to thinking that it doesn't really matter if you don't have something to say every ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago

The last few days have been a bit too much of a whirl for me to manage a fresh edition each day. It's been that kind of year. Hope you don't mind.I’ve been coming around to thinking that it doesn't really matter if you don't have something to say every ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack3 days ago - All I Want For Christmas

The worms will live in every hostIt's hard to pick which one they eat the mostThe horrible people, the horrible peopleIt's as anatomic as the size of your steepleCapitalism has made it this wayOld-fashioned fascism will take it awaySongwriter: Twiggy Ramirez Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago

The worms will live in every hostIt's hard to pick which one they eat the mostThe horrible people, the horrible peopleIt's as anatomic as the size of your steepleCapitalism has made it this wayOld-fashioned fascism will take it awaySongwriter: Twiggy Ramirez Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel4 days ago - The 1 Good Thing Left In Journalism

Hi,It’s almost Christmas Day which means it is almost my birthday, where you will find me whimpering in the corner clutching a warm bottle of Baileys.If you’re out of ideas for presents (and truly desperate) then it is possible to gift a full Webworm subscription to a friend (or enemy) ...David FarrierBy David Farrier4 days ago

Hi,It’s almost Christmas Day which means it is almost my birthday, where you will find me whimpering in the corner clutching a warm bottle of Baileys.If you’re out of ideas for presents (and truly desperate) then it is possible to gift a full Webworm subscription to a friend (or enemy) ...David FarrierBy David Farrier4 days ago - Bernard’s Picks ‘n’ Mixes for Monday, December 23

This morning’s six standouts for me at 6.30am include:Rachel Helyer Donaldson’s scoop via RNZ last night of cuts to maternity jobs in the health system;Maddy Croad’s scoop via The Press-$ this morning on funding cuts for Christchurch’s biggest food rescue charity;Benedict Collins’ scoop last night via 1News on a last-minute ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago

This morning’s six standouts for me at 6.30am include:Rachel Helyer Donaldson’s scoop via RNZ last night of cuts to maternity jobs in the health system;Maddy Croad’s scoop via The Press-$ this morning on funding cuts for Christchurch’s biggest food rescue charity;Benedict Collins’ scoop last night via 1News on a last-minute ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey4 days ago - 2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #51

A listing of 25 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, December 15, 2024 thru Sat, December 21, 2024. Based on feedback we received, this week's roundup is the first one published soleley by category. We are still interested in ...4 days ago

A listing of 25 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, December 15, 2024 thru Sat, December 21, 2024. Based on feedback we received, this week's roundup is the first one published soleley by category. We are still interested in ...4 days ago - Dance Magic

Well, I've been there, sitting in that same chairWhispering that same prayer half a million timesIt's a lie, though buried in disciplesOne page of the Bible isn't worth a lifeThere's nothing wrong with youIt's true, it's trueThere's something wrong with the villageWith the villageSomething wrong with the villageSongwriters: Andrew Jackson ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago

Well, I've been there, sitting in that same chairWhispering that same prayer half a million timesIt's a lie, though buried in disciplesOne page of the Bible isn't worth a lifeThere's nothing wrong with youIt's true, it's trueThere's something wrong with the villageWith the villageSomething wrong with the villageSongwriters: Andrew Jackson ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel5 days ago - Government Forces Universities to Enforce “Free Speech” While Limiting Universities̵...

ACT would like to dictate what universities can and can’t say. We knew it was coming. It was outlined in the coalition agreement and has become part of Seymour’s strategy of “emphasising public funding” to prevent people from opposing him and his views—something he also uses to try and de-platform ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi5 days ago

ACT would like to dictate what universities can and can’t say. We knew it was coming. It was outlined in the coalition agreement and has become part of Seymour’s strategy of “emphasising public funding” to prevent people from opposing him and his views—something he also uses to try and de-platform ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi5 days ago - Fact brief – Are we heading into an ‘ice age’?

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park from the Gigafact team in collaboration with members from our team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Are we heading ...5 days ago

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park from the Gigafact team in collaboration with members from our team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Are we heading ...5 days ago - As Our Power Lessens: Published

So the Solstice has arrived – Summer in this part of the world, Winter for the Northern Hemisphere. And with it, the publication my new Norse dark-fantasy piece, As Our Power Lessens at Eternal Haunted Summer: https://eternalhauntedsummer.com/issues/winter-solstice-2024/as-our-power-lessens/ As previously noted, this one is very ‘wyrd’, and Northern Theory of Courage. ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2215 days ago

So the Solstice has arrived – Summer in this part of the world, Winter for the Northern Hemisphere. And with it, the publication my new Norse dark-fantasy piece, As Our Power Lessens at Eternal Haunted Summer: https://eternalhauntedsummer.com/issues/winter-solstice-2024/as-our-power-lessens/ As previously noted, this one is very ‘wyrd’, and Northern Theory of Courage. ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2215 days ago - By Any Other Name.

The Natural Choice: As a starter for ten percent of the Party Vote, “saving the planet” is a very respectable objective. Young voters, in particular, raised on the dire (if unheeded) warnings of climate scientists, and the irrefutable evidence of devastating weather events linked to global warming, vote Green. After ...5 days ago

The Natural Choice: As a starter for ten percent of the Party Vote, “saving the planet” is a very respectable objective. Young voters, in particular, raised on the dire (if unheeded) warnings of climate scientists, and the irrefutable evidence of devastating weather events linked to global warming, vote Green. After ...5 days ago - Bernard’s last Saturday Soliloquy for 2024

The Government cancelled 60% of Kāinga Ora’s new builds next year, even though the land for them was already bought, the consents were consented and there are builders unemployed all over the place. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that mattered in Aotearoa’s political ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago

The Government cancelled 60% of Kāinga Ora’s new builds next year, even though the land for them was already bought, the consents were consented and there are builders unemployed all over the place. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that mattered in Aotearoa’s political ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago - Bernard’s Picks ‘n’ Mixes for Saturday, December 21

Photo by CHUTTERSNAP on UnsplashEvery morning I get up at 3am to go around the traps of news sites in Aotearoa and globally. I pick out the top ones from my point of view and have been putting them into my Dawn Chorus email, which goes out with a podcast. ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago

Photo by CHUTTERSNAP on UnsplashEvery morning I get up at 3am to go around the traps of news sites in Aotearoa and globally. I pick out the top ones from my point of view and have been putting them into my Dawn Chorus email, which goes out with a podcast. ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey6 days ago - 2024 OIA stats

Over on Kikorangi Newsroom's Marc Daalder has published his annual OIA stats. So I thought I'd do mine: 82 OIA requests sent in 2024 7 posts based on those requests 20 average working days to receive a response Ministry of Justice was my most-requested entity, ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago

Over on Kikorangi Newsroom's Marc Daalder has published his annual OIA stats. So I thought I'd do mine: 82 OIA requests sent in 2024 7 posts based on those requests 20 average working days to receive a response Ministry of Justice was my most-requested entity, ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago - Climate Change: A perverse incentive

The government published its first Biennial Transparency Report under the Paris Agreement yesterday, and the media has correctly noted that it is missing any plan to actually meet our target. While it hypes domestic emissions reductions so far - which have been good, but will likely get worse thanks to ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago

The government published its first Biennial Transparency Report under the Paris Agreement yesterday, and the media has correctly noted that it is missing any plan to actually meet our target. While it hypes domestic emissions reductions so far - which have been good, but will likely get worse thanks to ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant6 days ago - Economic Bulletin December 2024

Welcome to the December 2024 Economic Bulletin. We have two monthly features in this edition. In the first, we discuss what the Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update from Treasury and the Budget Policy Statement from the Minister of Finance tell us about the fiscal position and what to ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald6 days ago

Welcome to the December 2024 Economic Bulletin. We have two monthly features in this edition. In the first, we discuss what the Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update from Treasury and the Budget Policy Statement from the Minister of Finance tell us about the fiscal position and what to ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald6 days ago - NZCTU make submission in opposition to Treaty Principles Bill

The NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi have submitted against the controversial Treaty Principles Bill, slamming the Bill as a breach of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and an attack on tino rangatiratanga and the collective rights of Tangata Whenua. “This Bill seeks to legislate for Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles that are ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald6 days ago

The NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi have submitted against the controversial Treaty Principles Bill, slamming the Bill as a breach of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and an attack on tino rangatiratanga and the collective rights of Tangata Whenua. “This Bill seeks to legislate for Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles that are ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald6 days ago - ZB’s Power Couple

I don't knowHow to say what's got to be saidI don't know if it's black or whiteThere's others see it redI don't get the answers rightI'll leave that to youIs this love out of fashionOr is it the time of yearAre these words distraction?To the words you want to hearSongwriters: ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel7 days ago

I don't knowHow to say what's got to be saidI don't know if it's black or whiteThere's others see it redI don't get the answers rightI'll leave that to youIs this love out of fashionOr is it the time of yearAre these words distraction?To the words you want to hearSongwriters: ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel7 days ago - Austerity thumps GDP most since 1991

Our economy has experienced its worst recession since 1991. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Friday, December 20 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast above and the daily Pick ‘n’ Mix below ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey7 days ago

Our economy has experienced its worst recession since 1991. Photo: Lynn Grieveson / The KākāMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Friday, December 20 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast above and the daily Pick ‘n’ Mix below ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey7 days ago - Weekly Roundup 20-December-2024

Twas the Friday before Christmas and all through the week we’ve been collecting stories for our final roundup of the year. As we start to wind down for the year we hope you all have a safe and happy Christmas and new year. If you’re travelling please be safe on ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland7 days ago

Twas the Friday before Christmas and all through the week we’ve been collecting stories for our final roundup of the year. As we start to wind down for the year we hope you all have a safe and happy Christmas and new year. If you’re travelling please be safe on ...Greater AucklandBy Greater Auckland7 days ago - The Hoon around the year to December 20, 2024

The podcast above of the weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers on Thursday night features co-hosts & talking about the year’s news with: on climate. Her book of the year was Tim Winton’s cli-fi novel Juice and she also mentioned Mike Joy’s memoir The Fight for Fresh Water. ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey7 days ago

The podcast above of the weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar for paying subscribers on Thursday night features co-hosts & talking about the year’s news with: on climate. Her book of the year was Tim Winton’s cli-fi novel Juice and she also mentioned Mike Joy’s memoir The Fight for Fresh Water. ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey7 days ago - The baby-boomers’ last gasp

The Government can head off to the holidays, entitled to assure itself that it has done more or less what it said it would do. The campaign last year promised to “get New Zealand back on track.” When you look at the basic promises—to trim back Government expenditure, toughen up ...PolitikBy Richard Harman7 days ago

The Government can head off to the holidays, entitled to assure itself that it has done more or less what it said it would do. The campaign last year promised to “get New Zealand back on track.” When you look at the basic promises—to trim back Government expenditure, toughen up ...PolitikBy Richard Harman7 days ago - Skeptical Science New Research for Week #51 2024

Open access notables An intensification of surface Earth’s energy imbalance since the late 20th century, Li et al., Communications Earth & Environment: Tracking the energy balance of the Earth system is a key method for studying the contribution of human activities to climate change. However, accurately estimating the surface energy balance ...1 week ago

Open access notables An intensification of surface Earth’s energy imbalance since the late 20th century, Li et al., Communications Earth & Environment: Tracking the energy balance of the Earth system is a key method for studying the contribution of human activities to climate change. However, accurately estimating the surface energy balance ...1 week ago - Join us at 5pm for 2024’s last Hoon

Photo by Mauricio Fanfa on UnsplashKia oraCome and join us for our weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar with paying subscribers to The Kākā for an hour at 5 pm today.Jump on this link on YouTube Livestream for our chat about the week’s news with myself , plus regular guests and , ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

Photo by Mauricio Fanfa on UnsplashKia oraCome and join us for our weekly ‘Hoon’ webinar with paying subscribers to The Kākā for an hour at 5 pm today.Jump on this link on YouTube Livestream for our chat about the week’s news with myself , plus regular guests and , ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - Christmas Gifts: Ageing Boomers, Laurie & Les, Talk Politics.

“Like you said, I’m an unreconstructed socialist. Everybody deserves to get something for Christmas.”“ONE OF THOSE had better be for me!” Hannah grinned, fascinated, as Laurie made his way, gingerly, to the bar, his arms full of gift-wrapped packages.“Of course!”, beamed Laurie. Depositing his armful on the bar-top and selecting ...1 week ago

“Like you said, I’m an unreconstructed socialist. Everybody deserves to get something for Christmas.”“ONE OF THOSE had better be for me!” Hannah grinned, fascinated, as Laurie made his way, gingerly, to the bar, his arms full of gift-wrapped packages.“Of course!”, beamed Laurie. Depositing his armful on the bar-top and selecting ...1 week ago - GDP Figures No Christmas Present for New Zealand

Data released by Statistics New Zealand today showed a significant slowdown in the economy over the past six months, with GDP falling by 1% in September, and 1.1% in June said CTU Economist Craig Renney. “The data shows that the size of the economy in GDP terms is now smaller ...NZCTUBy Stella Whitfield1 week ago

Data released by Statistics New Zealand today showed a significant slowdown in the economy over the past six months, with GDP falling by 1% in September, and 1.1% in June said CTU Economist Craig Renney. “The data shows that the size of the economy in GDP terms is now smaller ...NZCTUBy Stella Whitfield1 week ago - Cheeseburgers and Stunt Monkeys

One last thing before I quitI never wanted any moreThan I could fit into my headI still remember every single word you saidAnd all the shit that somehow came along with itStill, there's one thing that comforts meSince I was always caged and now I'm freeSongwriters: David Grohl / Georg ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago

One last thing before I quitI never wanted any moreThan I could fit into my headI still remember every single word you saidAnd all the shit that somehow came along with itStill, there's one thing that comforts meSince I was always caged and now I'm freeSongwriters: David Grohl / Georg ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago - MSD rejecting 220 pleas for food grants each day

Sparse offerings outside a Te Kauwhata church. Meanwhile, the Government is cutting spending in ways that make thousands of hungry children even hungrier, while also cutting funding for the charities that help them. It’s also doing that while winding back new building of affordable housing that would allow parents to ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

Sparse offerings outside a Te Kauwhata church. Meanwhile, the Government is cutting spending in ways that make thousands of hungry children even hungrier, while also cutting funding for the charities that help them. It’s also doing that while winding back new building of affordable housing that would allow parents to ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - The Wing Parties’ Economic Policies.

It is difficult to make sense of the Luxon Coalition Government’s economic management.This end-of-year review about the state of economic management – the state of the economy was last week – is not going to cover the National Party contribution. Frankly, like every other careful observer, I cannot make up ...PunditBy Brian Easton1 week ago

It is difficult to make sense of the Luxon Coalition Government’s economic management.This end-of-year review about the state of economic management – the state of the economy was last week – is not going to cover the National Party contribution. Frankly, like every other careful observer, I cannot make up ...PunditBy Brian Easton1 week ago - Back on Track

This morning I awoke to the lovely news that we are firmly back on track, that is if the scale was reversed.NZ ranks low in global economic comparisonsNew Zealand's economy has been ranked 33rd out of 37 in an international comparison of which have done best in 2024.Economies were ranked ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī1 week ago

This morning I awoke to the lovely news that we are firmly back on track, that is if the scale was reversed.NZ ranks low in global economic comparisonsNew Zealand's economy has been ranked 33rd out of 37 in an international comparison of which have done best in 2024.Economies were ranked ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī1 week ago - Book Review: How Big Things Get Done

This is a guest post by George Weeks, reviewing a book called How Big Things Get Done by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner Want to know how to do something big? Ask someone who has done it before! Professor Bent Flyvbjerg has spent his career studying megaprojects. In 2023, ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post1 week ago

This is a guest post by George Weeks, reviewing a book called How Big Things Get Done by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner Want to know how to do something big? Ask someone who has done it before! Professor Bent Flyvbjerg has spent his career studying megaprojects. In 2023, ...Greater AucklandBy Guest Post1 week ago - Gordon Campbell On Why We Can’t Survive Two More Years Of This

Remember those silent movies where the heroine is tied to the railway tracks or going over the waterfall in a barrel? Finance Minister Nicola Willis seems intent on portraying herself as that damsel in distress. According to Willis, this country’s current economic problems have all been caused by the spending ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor1 week ago

Remember those silent movies where the heroine is tied to the railway tracks or going over the waterfall in a barrel? Finance Minister Nicola Willis seems intent on portraying herself as that damsel in distress. According to Willis, this country’s current economic problems have all been caused by the spending ...WerewolfBy ScoopEditor1 week ago - Dragging our way towards the finish line, the end of this year can’t come soon enough for many…

Similar to the cuts and the austerity drive imposed by Ruth Richardson in the 1990’s, an era which to all intents and purposes we’ve largely fiddled around the edges with fixing in the time since – over, to be fair, several administrations – whilst trying our best it seems to ...exhALANtBy exhalantblog1 week ago

Similar to the cuts and the austerity drive imposed by Ruth Richardson in the 1990’s, an era which to all intents and purposes we’ve largely fiddled around the edges with fixing in the time since – over, to be fair, several administrations – whilst trying our best it seems to ...exhALANtBy exhalantblog1 week ago - Handling Democracy.

String-Pulling in the Dark: For the democratic process to be meaningful it must also be public. WITH TRUST AND CONFIDENCE in New Zealand’s politicians and journalists steadily declining, restoring those virtues poses a daunting challenge. Just how daunting is made clear by comparing the way politicians and journalists treated New Zealanders ...1 week ago

String-Pulling in the Dark: For the democratic process to be meaningful it must also be public. WITH TRUST AND CONFIDENCE in New Zealand’s politicians and journalists steadily declining, restoring those virtues poses a daunting challenge. Just how daunting is made clear by comparing the way politicians and journalists treated New Zealanders ...1 week ago - Open letter to the Minister of Dwindling Finances

Dear Nicola Willis, thank you for letting us know in so many words that the swingeing austerity hasn't worked.By in so many words I mean the bit where you said, Here is a sea of red ink in which we are drowning after twelve months of savage cost cutting and ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 week ago

Dear Nicola Willis, thank you for letting us know in so many words that the swingeing austerity hasn't worked.By in so many words I mean the bit where you said, Here is a sea of red ink in which we are drowning after twelve months of savage cost cutting and ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 week ago - Open Government: The joke ends

The Open Government Partnership is a multilateral organisation committed to advancing open government. Countries which join are supposed to co-create regular action plans with civil society, committing to making verifiable improvements in transparency, accountability, participation, or technology and innovation for the above. And they're held to account through an Independent ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago

The Open Government Partnership is a multilateral organisation committed to advancing open government. Countries which join are supposed to co-create regular action plans with civil society, committing to making verifiable improvements in transparency, accountability, participation, or technology and innovation for the above. And they're held to account through an Independent ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago - An unusual sort of press conference

Today I tuned into something strange: a press conference that didn’t make my stomach churn or the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. Which was strange, because it was about the torture of children. It was the announcement by Erica Stanford — on her own, unusually ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi1 week ago

Today I tuned into something strange: a press conference that didn’t make my stomach churn or the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. Which was strange, because it was about the torture of children. It was the announcement by Erica Stanford — on her own, unusually ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi1 week ago - This substack has talked about this government’s seeming corruption & pro-corporate issues...

This is a must watch, and puts on brilliant and practical display the implications and mechanics of fast-track law corruption and weakness.CLICK HERE: LINK TO WATCH VIDEOOur news media as it is set up is simply not equipped to deal with the brazen disinformation and corruption under this right wing ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī1 week ago

This is a must watch, and puts on brilliant and practical display the implications and mechanics of fast-track law corruption and weakness.CLICK HERE: LINK TO WATCH VIDEOOur news media as it is set up is simply not equipped to deal with the brazen disinformation and corruption under this right wing ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī1 week ago - NZCTU: Minister needs to listen to the evidence on engineered stone ban

NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi Acting Secretary Erin Polaczuk is welcoming the announcement from Minister of Workplace Relations and Safety Brooke van Velden that she is opening consultation on engineered stone and is calling on her to listen to the evidence and implement a total ban of the product. “We need ...NZCTUBy Stella Whitfield1 week ago

NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi Acting Secretary Erin Polaczuk is welcoming the announcement from Minister of Workplace Relations and Safety Brooke van Velden that she is opening consultation on engineered stone and is calling on her to listen to the evidence and implement a total ban of the product. “We need ...NZCTUBy Stella Whitfield1 week ago - Wednesday 18 December

The Government has announced a 1.5% increase in the minimum wage from 1 April 2025, well below forecast inflation of 2.5%. Unions have reacted strongly and denounced it as a real terms cut. PSA and the CTU are opposing a new round of staff cuts at WorkSafe, which they say ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald1 week ago

The Government has announced a 1.5% increase in the minimum wage from 1 April 2025, well below forecast inflation of 2.5%. Unions have reacted strongly and denounced it as a real terms cut. PSA and the CTU are opposing a new round of staff cuts at WorkSafe, which they say ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald1 week ago - Can the government change its mind on the ferries?

The decision to unilaterally repudiate the contract for new Cook Strait ferries is beginning to look like one of the stupidest decisions a New Zealand government ever made. While cancelling the ferries and their associated port infrastructure may have made this year's books look good, it means higher costs later, ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago

The decision to unilaterally repudiate the contract for new Cook Strait ferries is beginning to look like one of the stupidest decisions a New Zealand government ever made. While cancelling the ferries and their associated port infrastructure may have made this year's books look good, it means higher costs later, ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago - Notes from Afar: Will Luxon Attend Waitangi Day? And Opposition Calls Out Nicola Willis for “C...

Hi there! I’ve been overseas recently, looking after a situation with a family member. So apologies if there any less than focused posts! Vanuatu has just had a significant 7.3 earthquake. Two MFAT staff are unaccounted for with local fatalities.It’s always sad to hear of such things happening.I think of ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī1 week ago

Hi there! I’ve been overseas recently, looking after a situation with a family member. So apologies if there any less than focused posts! Vanuatu has just had a significant 7.3 earthquake. Two MFAT staff are unaccounted for with local fatalities.It’s always sad to hear of such things happening.I think of ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī1 week ago - Member’s morning

Today is a special member's morning, scheduled to make up for the government's theft of member's days throughout the year. First up was the first reading of Greg Fleming's Crimes (Increased Penalties for Slavery Offences) Amendment Bill, which was passed unanimously. Currently the House is debating the third reading of ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago

Today is a special member's morning, scheduled to make up for the government's theft of member's days throughout the year. First up was the first reading of Greg Fleming's Crimes (Increased Penalties for Slavery Offences) Amendment Bill, which was passed unanimously. Currently the House is debating the third reading of ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago - Going Backwards

We're going backwardsIgnoring the realitiesGoing backwardsAre you counting all the casualties?We are not there yetWhere we need to beWe are still in debtTo our insanitiesSongwriter: Martin Gore Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago

We're going backwardsIgnoring the realitiesGoing backwardsAre you counting all the casualties?We are not there yetWhere we need to beWe are still in debtTo our insanitiesSongwriter: Martin Gore Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago - Blaming Treasury & Labour, Willis looks for even more Austerity

Willis blamed Treasury for changing its productivity assumptions and Labour’s spending increases since Covid for the worsening Budget outlook. Photo: Getty ImagesMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Wednesday, December 18 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast above ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

Willis blamed Treasury for changing its productivity assumptions and Labour’s spending increases since Covid for the worsening Budget outlook. Photo: Getty ImagesMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Wednesday, December 18 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast above ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - December-24 AT Board Meeting

Today the Auckland Transport board meet for the last time this year. For those interested (and with time to spare), you can follow along via this MS Teams link from 10am. I’ve taken a quick look through the agenda items to see what I think the most interesting aspects are. ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L1 week ago

Today the Auckland Transport board meet for the last time this year. For those interested (and with time to spare), you can follow along via this MS Teams link from 10am. I’ve taken a quick look through the agenda items to see what I think the most interesting aspects are. ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L1 week ago - The Making of a Mental Health Rockstar

Hi,If you’re a New Zealander — you know who Mike King is. He is the face of New Zealand’s battle against mental health problems. He can be loud and brash. He raises, and is entrusted with, a lot of cash. Last year his “I Am Hope” charity reported a revenue ...David FarrierBy David Farrier1 week ago

Hi,If you’re a New Zealander — you know who Mike King is. He is the face of New Zealand’s battle against mental health problems. He can be loud and brash. He raises, and is entrusted with, a lot of cash. Last year his “I Am Hope” charity reported a revenue ...David FarrierBy David Farrier1 week ago - It could have been worse

Probably about the only consolation available from yesterday’s unveiling of the Half-Yearly Economic and Fiscal Update (HYEFU) is that it could have been worse. Though Finance Minister Nicola Willis has tightened the screws on future government spending, she has resisted the calls from hard-line academics, fiscal purists and fiscal hawks ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 week ago

Probably about the only consolation available from yesterday’s unveiling of the Half-Yearly Economic and Fiscal Update (HYEFU) is that it could have been worse. Though Finance Minister Nicola Willis has tightened the screws on future government spending, she has resisted the calls from hard-line academics, fiscal purists and fiscal hawks ...PolitikBy Richard Harman1 week ago - The Deep Divisions of Local Government

The right have a stupid saying that is only occasionally true:When is democracy not democracy? When it hasn’t been voted on.While not true in regards to branches of government such as the judiciary, it’s a philosophy that probably should apply to recently-elected local government councillors. Nevertheless, this concept seemed to ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi1 week ago

The right have a stupid saying that is only occasionally true:When is democracy not democracy? When it hasn’t been voted on.While not true in regards to branches of government such as the judiciary, it’s a philosophy that probably should apply to recently-elected local government councillors. Nevertheless, this concept seemed to ...Sapphi’s SubstackBy Sapphi1 week ago - Willis’ austerity strategy just isn’t working

Long story short: the Government’s austerity policy has driven the economy into a deeper and longer recession that means it will have to borrow $20 billion more over the next four years than it expected just six months ago. Treasury’s latest forecasts show the National-ACT-NZ First Government’s fiscal strategy of ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

Long story short: the Government’s austerity policy has driven the economy into a deeper and longer recession that means it will have to borrow $20 billion more over the next four years than it expected just six months ago. Treasury’s latest forecasts show the National-ACT-NZ First Government’s fiscal strategy of ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - Sabin 33 #7 – Are solar projects hurting farmers and rural communities?

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia ...1 week ago

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia ...1 week ago - Join us for a pop-up Hoon at 5pm on HYEFU

The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

- ‘Ideas Worth Saving’: A Call for Papers

Some years ago, I found myself pondering the power of literature to endure. Or at least the power of some of it to endure, while the rest vanishes in mere decades: https://phuulishfellow.wordpress.com/2019/08/07/look-on-my-works-ye-mighty-and-despair-the-literary-future/. I have similarly had fun with the subject in some of my short stories, such as Another Alexandria ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2211 week ago

Some years ago, I found myself pondering the power of literature to endure. Or at least the power of some of it to endure, while the rest vanishes in mere decades: https://phuulishfellow.wordpress.com/2019/08/07/look-on-my-works-ye-mighty-and-despair-the-literary-future/. I have similarly had fun with the subject in some of my short stories, such as Another Alexandria ...A Phuulish FellowBy strda2211 week ago - Corrections is torturing prisoners again

In 1998, in the wake of the Paremoremo Prison riot, the Department of Corrections established the "Behaviour Management Regime". Prisoners were locked in their cells for 22 or 23 hours a day, with no fresh air, no exercise, no social contact, no entertainment, and in some cases no clothes and ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago

In 1998, in the wake of the Paremoremo Prison riot, the Department of Corrections established the "Behaviour Management Regime". Prisoners were locked in their cells for 22 or 23 hours a day, with no fresh air, no exercise, no social contact, no entertainment, and in some cases no clothes and ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago - HYEFU and BPS data shows New Zealand is way off track

New data released by the Treasury shows that the economic policies of this Government have made things worse in the year since they took office, said NZCTU Economist Craig Renney. “Our fiscal indicators are all heading in the wrong direction – with higher levels of debt, a higher deficit, and ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald1 week ago

New data released by the Treasury shows that the economic policies of this Government have made things worse in the year since they took office, said NZCTU Economist Craig Renney. “Our fiscal indicators are all heading in the wrong direction – with higher levels of debt, a higher deficit, and ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald1 week ago - “Better economic management”

At the 2023 election, National basically ran on a platform of being better economic managers. So how'd that turn out for us? In just one year, they've fucked us for two full political terms: The government's books are set to remain deeply in the red for the near term ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago

At the 2023 election, National basically ran on a platform of being better economic managers. So how'd that turn out for us? In just one year, they've fucked us for two full political terms: The government's books are set to remain deeply in the red for the near term ...No Right TurnBy Idiot/Savant1 week ago - Shameless, clueless

AUSTERITYText within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedMy spreadsheet insists This pain leads straight to glory (File not found) Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 week ago

AUSTERITYText within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedMy spreadsheet insists This pain leads straight to glory (File not found) Read more ...More Than A FeildingBy David Slack1 week ago - Minimum wage ‘increase’ is an effective cut

The NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi are saying that the Government should do the right thing and deliver minimum wage increases that don’t see workers fall further behind, in response to today’s announcement that the minimum wage will only be increased by 1.5%, well short of forecast inflation. “With inflation forecast ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald1 week ago

The NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi are saying that the Government should do the right thing and deliver minimum wage increases that don’t see workers fall further behind, in response to today’s announcement that the minimum wage will only be increased by 1.5%, well short of forecast inflation. “With inflation forecast ...NZCTUBy Jack McDonald1 week ago - Crazy ’bout a Sharp-dressed Man

Oh, I weptFor daysFilled my eyesWith silly tearsOh, yeaBut I don'tCare no moreI don't care ifMy eyes get soreSongwriters: Paul Rodgers / Paul Kossoff. Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago

Oh, I weptFor daysFilled my eyesWith silly tearsOh, yeaBut I don'tCare no moreI don't care ifMy eyes get soreSongwriters: Paul Rodgers / Paul Kossoff. Read more ...Nick’s KōreroBy Nick Rockel1 week ago - How much should you worry about a collapse of the Atlantic conveyor belt?

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Bob Henson In this aerial view, fingers of meltwater flow from the melting Isunnguata Sermia glacier descending from the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 11, 2024, near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. According to the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE), the ...1 week ago

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Bob Henson In this aerial view, fingers of meltwater flow from the melting Isunnguata Sermia glacier descending from the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 11, 2024, near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. According to the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE), the ...1 week ago - 8% ACT Party Creates One Ring To Rule Them All

In August, I wrote an article about David Seymour1 with a video of his testimony, to warn that there were grave dangers to his Ministry of Regulation:David Seymour's Ministry of Slush Hides Far Greater RisksWhy Seymour's exorbitant waste of taxpayers' money could be the least of concernThe money for Seymour ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī1 week ago

In August, I wrote an article about David Seymour1 with a video of his testimony, to warn that there were grave dangers to his Ministry of Regulation:David Seymour's Ministry of Slush Hides Far Greater RisksWhy Seymour's exorbitant waste of taxpayers' money could be the least of concernThe money for Seymour ...Mountain TuiBy Mountain Tūī1 week ago - When austerity worsens public debt & cuts GDP

Willis is expected to have to reveal the bitter fiscal fruits of her austerity strategy in the HYEFU later today. Photo: Lynn Grieveson/TheKakaMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Tuesday, December 17 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago

Willis is expected to have to reveal the bitter fiscal fruits of her austerity strategy in the HYEFU later today. Photo: Lynn Grieveson/TheKakaMōrena. Long stories short, the six things that matter in Aotearoa’s political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Tuesday, December 17 in The Kākā’s Dawn Chorus podcast ...The KakaBy Bernard Hickey1 week ago - Govt to double number of toll roads

On Friday the government announced it would double the number of toll roads in New Zealand as well as make a few other changes to how toll roads are used in the country. The real issue though is not that tolling is being used but the suggestion it will make ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L1 week ago

On Friday the government announced it would double the number of toll roads in New Zealand as well as make a few other changes to how toll roads are used in the country. The real issue though is not that tolling is being used but the suggestion it will make ...Greater AucklandBy Matt L1 week ago

Related Posts

- National’s Greatest Misses 2023-4

National has only been in power for a year, but everywhere you look, its choices are taking New Zealand a long way backwards. In no particular order, here are the National Government's Top 50 Greatest Misses of its first year in power. ...6 days ago

National has only been in power for a year, but everywhere you look, its choices are taking New Zealand a long way backwards. In no particular order, here are the National Government's Top 50 Greatest Misses of its first year in power. ...6 days ago - Release: Minister’s plan for tertiary sector a backwards step

Returning to the model that was failing for most polytechnics and Institutes of Technology is not the answer. ...6 days ago

Returning to the model that was failing for most polytechnics and Institutes of Technology is not the answer. ...6 days ago - Release: National buries 1019 planned homes

It’s been revealed that National has cancelled 60 percent of its housing projects planned before mid-2025 amidst housing woes. ...7 days ago

It’s been revealed that National has cancelled 60 percent of its housing projects planned before mid-2025 amidst housing woes. ...7 days ago - Release: Rule-Czar bill a right-wing power grab

The Government is quietly undertaking consultation on the dangerous Regulatory Standards Bill over the Christmas period to avoid too much attention. ...7 days ago

The Government is quietly undertaking consultation on the dangerous Regulatory Standards Bill over the Christmas period to avoid too much attention. ...7 days ago - Release: Why not both? Luxon shuns Waitangi celebrations

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon is running away from problems of his own creation, with his decision not to go to Waitangi. ...1 week ago

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon is running away from problems of his own creation, with his decision not to go to Waitangi. ...1 week ago - Govt’s ‘free speech’ legislation stokes fear, not freedom

The Government’s planned changes to the freedom of speech obligations of universities is little more than a front for stoking the political fires of disinformation and fear, placing teachers and students in the crosshairs. ...1 week ago

The Government’s planned changes to the freedom of speech obligations of universities is little more than a front for stoking the political fires of disinformation and fear, placing teachers and students in the crosshairs. ...1 week ago - Release: Nicola Willis spirals country deeper into recession

The economy shrank 1% this quarter and New Zealand has tumbled into the depths of a recession of Nicola Willis’ making. ...1 week ago

The economy shrank 1% this quarter and New Zealand has tumbled into the depths of a recession of Nicola Willis’ making. ...1 week ago - Release: Hikes for company directors but not ordinary Kiwis

1 week ago

- ECE no place to cut corners

The Ministry of Regulation’s report into Early Childhood Education (ECE) in Aotearoa raises serious concerns about the possibility of lowering qualification requirements, undermining quality and risking worse outcomes for tamariki, whānau, and kaiako. ...1 week ago

The Ministry of Regulation’s report into Early Childhood Education (ECE) in Aotearoa raises serious concerns about the possibility of lowering qualification requirements, undermining quality and risking worse outcomes for tamariki, whānau, and kaiako. ...1 week ago - Release: Strengthening Justice Services for New Zealanders

A Bill to modernise the role of Justices of the Peace (JP), ensuring they remain active in their communities and connected with other JPs, has been put into the ballot. ...1 week ago

A Bill to modernise the role of Justices of the Peace (JP), ensuring they remain active in their communities and connected with other JPs, has been put into the ballot. ...1 week ago - Release: Labour will continue fight against destructive projects

Labour will continue to fight unsustainable and destructive projects that are able to leap-frog environment protection under National’s Fast-track Approvals Bill. ...1 week ago

Labour will continue to fight unsustainable and destructive projects that are able to leap-frog environment protection under National’s Fast-track Approvals Bill. ...1 week ago - Green Government will revoke dodgy fast-track projects

The Green Party has warned that a Green Government will revoke the consents of companies who override environmental protections as part of Fast-Track legislation being passed today. ...1 week ago

The Green Party has warned that a Green Government will revoke the consents of companies who override environmental protections as part of Fast-Track legislation being passed today. ...1 week ago - Government for the wealthy keeps pushing austerity

The Green Party says the Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update shows how the Government is failing to address the massive social and infrastructure deficits our country faces. ...1 week ago

The Green Party says the Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update shows how the Government is failing to address the massive social and infrastructure deficits our country faces. ...1 week ago - Release: Visa changes let migrant workers be paid less

The Government’s latest move to reduce the earnings of migrant workers will not only hurt migrants but it will drive down the wages of Kiwi workers. ...1 week ago

The Government’s latest move to reduce the earnings of migrant workers will not only hurt migrants but it will drive down the wages of Kiwi workers. ...1 week ago - Release: Nightmare before Christmas for Nicola Willis

With more debt and a larger deficit, Nicola Willis’ reputation is in tatters after her failure to return the Government’s books to surplus. ...1 week ago

With more debt and a larger deficit, Nicola Willis’ reputation is in tatters after her failure to return the Government’s books to surplus. ...1 week ago - Warning to Fast-Track Applicants – ‘Exploit the Whenua, Face the Consequences’

Te Pāti Māori has this morning issued a stern warning to Fast-Track applicants with interests in mining, pledging to hold them accountable through retrospective liability and to immediately revoke Fast-Track consents under a future Te Pāti Māori government. This warning comes ahead of today’s third reading of the Fast-Track Approvals ...1 week ago

Te Pāti Māori has this morning issued a stern warning to Fast-Track applicants with interests in mining, pledging to hold them accountable through retrospective liability and to immediately revoke Fast-Track consents under a future Te Pāti Māori government. This warning comes ahead of today’s third reading of the Fast-Track Approvals ...1 week ago - Release: Govt cuts wages for lowest paid NZers… again

For the second year running, the government has effectively cut wages for the lowest paid workers in New Zealand. ...1 week ago

For the second year running, the government has effectively cut wages for the lowest paid workers in New Zealand. ...1 week ago - Govt’s miserly 1.5% minimum wage will take workers backwards

The Government’s announcement today of a 1.5 per cent increase to minimum wage is another blow for workers, with inflation projected to exceed the increase, meaning it’s a real terms pay reduction for many. ...1 week ago

The Government’s announcement today of a 1.5 per cent increase to minimum wage is another blow for workers, with inflation projected to exceed the increase, meaning it’s a real terms pay reduction for many. ...1 week ago - Release: Govt shirking responsibility for rate hikes

All the Government has achieved from its announcement today is to continue to push responsibility back on councils for its own lack of action to help bring down skyrocketing rates. ...1 week ago

All the Government has achieved from its announcement today is to continue to push responsibility back on councils for its own lack of action to help bring down skyrocketing rates. ...1 week ago - Luxon’s ‘localism’ strikes again

The Government has used its final post-Cabinet press conference of the year to punch down on local government without offering any credible solutions to the issues our councils are facing. ...1 week ago

The Government has used its final post-Cabinet press conference of the year to punch down on local government without offering any credible solutions to the issues our councils are facing. ...1 week ago - Release: Govt breaks promise on EV chargers

The Government has failed to keep its promise to ‘super charge’ the EV network, delivering just 292 chargers - less than half of the 670 chargers needed to meet its target. ...1 week ago

The Government has failed to keep its promise to ‘super charge’ the EV network, delivering just 292 chargers - less than half of the 670 chargers needed to meet its target. ...1 week ago - Greens call for end to subsidies for Methanex

The Green Party is calling for the Government to stop subsidising the largest user of the country’s gas supplies, Methanex, following a report highlighting the multi-national’s disproportionate influence on energy prices in Aotearoa. ...1 week ago

The Green Party is calling for the Government to stop subsidising the largest user of the country’s gas supplies, Methanex, following a report highlighting the multi-national’s disproportionate influence on energy prices in Aotearoa. ...1 week ago - Govt child poverty targets allow for increase in poverty

The Green Party is appalled with the Government’s new child poverty targets that are based on a new ‘persistent poverty’ measure that could be met even with an increase in child poverty. ...2 weeks ago

The Green Party is appalled with the Government’s new child poverty targets that are based on a new ‘persistent poverty’ measure that could be met even with an increase in child poverty. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Four weeks annual leave under threat

The Government’s attack on workers continues with news it is scrapping work on the Holidays Act. ...2 weeks ago

The Government’s attack on workers continues with news it is scrapping work on the Holidays Act. ...2 weeks ago - Govt’s emissions plan for measly 1% reduction

New independent analysis has revealed that the Government’s Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) will reduce emissions by a measly 1 per cent by 2030, failing to set us up for the future and meeting upcoming targets. ...2 weeks ago

New independent analysis has revealed that the Government’s Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) will reduce emissions by a measly 1 per cent by 2030, failing to set us up for the future and meeting upcoming targets. ...2 weeks ago - Greens stand in solidarity with Whakaata Māori on sad day

The loss of 27 kaimahi at Whakaata Māori and the end of its daily news bulletin is a sad day for Māori media and another step backwards for Te Tiriti o Waitangi justice. ...2 weeks ago

The loss of 27 kaimahi at Whakaata Māori and the end of its daily news bulletin is a sad day for Māori media and another step backwards for Te Tiriti o Waitangi justice. ...2 weeks ago - Sanctions regime to create more hardship for families

Yesterday the Government passed cruel legislation through first reading to establish a new beneficiary sanction regime that will ultimately mean more households cannot afford the basic essentials. ...2 weeks ago

Yesterday the Government passed cruel legislation through first reading to establish a new beneficiary sanction regime that will ultimately mean more households cannot afford the basic essentials. ...2 weeks ago - Govt gifts renters housing anxiety for Christmas

Today's passing of the Government's Residential Tenancies Amendment Bill–which allows landlords to end tenancies with no reason–ignores the voice of the people and leaves renters in limbo ahead of the festive season. ...2 weeks ago

Today's passing of the Government's Residential Tenancies Amendment Bill–which allows landlords to end tenancies with no reason–ignores the voice of the people and leaves renters in limbo ahead of the festive season. ...2 weeks ago - Release: National Party urged to support modern slavery legislation

Labour is urging the Prime Minister to walk the talk and support legislation combating modern slavery. ...2 weeks ago

Labour is urging the Prime Minister to walk the talk and support legislation combating modern slavery. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Labour has lost confidence in the Speaker

The Speaker of the New Zealand Parliament made an unprecedented decision on the government amendment to the Fast Track Approvals Bill last night. ...2 weeks ago

The Speaker of the New Zealand Parliament made an unprecedented decision on the government amendment to the Fast Track Approvals Bill last night. ...2 weeks ago - One year on, still no progress on new ferries

Today’s announcement from the Government on its plan for new ferries throws more uncertainty on the future of the country’s rail network. ...2 weeks ago

Today’s announcement from the Government on its plan for new ferries throws more uncertainty on the future of the country’s rail network. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Nicola Willis’ smaller ferries will cost more

After wasting a year, Nicola Willis has delivered a worse deal for the Cook Strait ferries that will end up being more expensive and take longer to arrive. ...2 weeks ago

After wasting a year, Nicola Willis has delivered a worse deal for the Cook Strait ferries that will end up being more expensive and take longer to arrive. ...2 weeks ago - Bill to sanction unlawful occupation of Palestine

Green Party co-leader Chlöe Swarbrick has today launched a Member’s Bill to sanction Israel for its unlawful presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, as the All Out For Gaza rally reaches Parliament. ...2 weeks ago

Green Party co-leader Chlöe Swarbrick has today launched a Member’s Bill to sanction Israel for its unlawful presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, as the All Out For Gaza rally reaches Parliament. ...2 weeks ago - Release: Labour fully supports greyhound racing ban

2 weeks ago

- Greyhound racing industry ban marks new era for animal welfare

After years of advocacy, the Green Party is very happy to hear the Government has listened to our collective voices and announced the closure of the greyhound racing industry, by 1 August 2026. ...2 weeks ago

After years of advocacy, the Green Party is very happy to hear the Government has listened to our collective voices and announced the closure of the greyhound racing industry, by 1 August 2026. ...2 weeks ago - Rangatahi voices must be centred in Government’s Relationship and Sexuality Education refresh

In response to a new report from ERO, the Government has acknowledged the urgent need for consistency across the curriculum for Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE) in schools. ...2 weeks ago

In response to a new report from ERO, the Government has acknowledged the urgent need for consistency across the curriculum for Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE) in schools. ...2 weeks ago - Govt introduces archaic anti-worker legislation

The Green Party is appalled at the Government introducing legislation that will make it easier to penalise workers fighting for better pay and conditions. ...2 weeks ago

The Green Party is appalled at the Government introducing legislation that will make it easier to penalise workers fighting for better pay and conditions. ...2 weeks ago - Winston Peters – Kinleith Mill Speech

Thank you for the invitation to speak with you tonight on behalf of the political party I belong to - which is New Zealand First. As we have heard before this evening the Kinleith Mill is proposing to reduce operations by focusing on pulp and discontinuing “lossmaking paper production”. They say that they are currently consulting on the plan to permanently shut ...2 weeks ago

Thank you for the invitation to speak with you tonight on behalf of the political party I belong to - which is New Zealand First. As we have heard before this evening the Kinleith Mill is proposing to reduce operations by focusing on pulp and discontinuing “lossmaking paper production”. They say that they are currently consulting on the plan to permanently shut ...2 weeks ago - Swarbrick calls on Auckland Mayor to end delay of revival of St James Theatre

Auckland Central MP, Chlöe Swarbrick, has written to Mayor Wayne Brown requesting he stop the unnecessary delays on St James Theatre’s restoration. ...3 weeks ago

Auckland Central MP, Chlöe Swarbrick, has written to Mayor Wayne Brown requesting he stop the unnecessary delays on St James Theatre’s restoration. ...3 weeks ago - He Ara Anamata: Greens launch Emissions Reduction Plan

Today, the Green Party of Aotearoa proudly unveils its new Emissions Reduction Plan–He Ara Anamata–a blueprint reimagining our collective future. ...3 weeks ago

Today, the Green Party of Aotearoa proudly unveils its new Emissions Reduction Plan–He Ara Anamata–a blueprint reimagining our collective future. ...3 weeks ago

Related Posts

- Be wise around water this summer

Kiwis planning a swim or heading out on a boat this summer should remember to stop and think about water safety, Sport & Recreation Minister Chris Bishop and ACC and Associate Transport Minister Matt Doocey say. “New Zealand’s beaches, lakes and rivers are some of the most beautiful in the ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz4 days ago

Kiwis planning a swim or heading out on a boat this summer should remember to stop and think about water safety, Sport & Recreation Minister Chris Bishop and ACC and Associate Transport Minister Matt Doocey say. “New Zealand’s beaches, lakes and rivers are some of the most beautiful in the ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz4 days ago - Drive safely this summer

The Government is urging Kiwis to drive safely this summer and reminding motorists that Police will be out in force to enforce the road rules, Transport Minister Simeon Brown says.“This time of year can be stressful and result in poor decision-making on our roads. Whether you are travelling to see ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz4 days ago

The Government is urging Kiwis to drive safely this summer and reminding motorists that Police will be out in force to enforce the road rules, Transport Minister Simeon Brown says.“This time of year can be stressful and result in poor decision-making on our roads. Whether you are travelling to see ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz4 days ago - Internationally-trained doctors jump at chance to boost health workforce

Health Minister Dr Shane Reti says Health New Zealand will move swiftly to support dozens of internationally-trained doctors already in New Zealand on their journey to employment here, after a tripling of sought-after examination places. “The Medical Council has delivered great news for hardworking overseas doctors who want to contribute ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz5 days ago

Health Minister Dr Shane Reti says Health New Zealand will move swiftly to support dozens of internationally-trained doctors already in New Zealand on their journey to employment here, after a tripling of sought-after examination places. “The Medical Council has delivered great news for hardworking overseas doctors who want to contribute ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz5 days ago - PM appoints business leader to APEC Business Advisory Council

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon has appointed Sarah Ottrey to the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC). “At my first APEC Summit in Lima, I experienced firsthand the role that ABAC plays in guaranteeing political leaders hear the voice of business,” Mr Luxon says. “New Zealand’s ABAC representatives are very well respected and ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon has appointed Sarah Ottrey to the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC). “At my first APEC Summit in Lima, I experienced firsthand the role that ABAC plays in guaranteeing political leaders hear the voice of business,” Mr Luxon says. “New Zealand’s ABAC representatives are very well respected and ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago - New intelligence oversight appointments

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon has announced four appointments to New Zealand’s intelligence oversight functions. The Honourable Robert Dobson KC has been appointed Chief Commissioner of Intelligence Warrants, and the Honourable Brendan Brown KC has been appointed as a Commissioner of Intelligence Warrants. The appointments of Hon Robert Dobson and Hon ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon has announced four appointments to New Zealand’s intelligence oversight functions. The Honourable Robert Dobson KC has been appointed Chief Commissioner of Intelligence Warrants, and the Honourable Brendan Brown KC has been appointed as a Commissioner of Intelligence Warrants. The appointments of Hon Robert Dobson and Hon ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago - New housing developments able to progress more quickly

Improvements in the average time it takes to process survey and title applications means housing developments can progress more quickly, Minister for Land Information Chris Penk says. “The government is resolutely focused on improving the building and construction pipeline,” Mr Penk says. “Applications to issue titles and subdivide land are ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago

Improvements in the average time it takes to process survey and title applications means housing developments can progress more quickly, Minister for Land Information Chris Penk says. “The government is resolutely focused on improving the building and construction pipeline,” Mr Penk says. “Applications to issue titles and subdivide land are ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago - Actions to speed up air travel delivering results

The Government’s measures to reduce airport wait times, and better transparency around flight disruptions is delivering encouraging early results for passengers ahead of the busy summer period, Transport Minister Simeon Brown says. “Improving the efficiency of air travel is a priority for the Government to give passengers a smoother, more reliable ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago

The Government’s measures to reduce airport wait times, and better transparency around flight disruptions is delivering encouraging early results for passengers ahead of the busy summer period, Transport Minister Simeon Brown says. “Improving the efficiency of air travel is a priority for the Government to give passengers a smoother, more reliable ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago - Ending contracted emergency housing in Rotorua

The Government today announced the intended closure of the Apollo Hotel as Contracted Emergency Housing (CEH) in Rotorua, Associate Housing Minister Tama Potaka says. This follows a 30 per cent reduction in the number of households in CEH in Rotorua since National came into Government. “Our focus is on ending CEH in the Whakarewarewa area starting ...BeehiveBy beehive.govt.nz6 days ago